Mineral mines are a great potential source of wealth in Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia but also have the potential to do great environmental harm. Three decades after the USSR, how is the industry doing in the South Caucasus?

Dashkasan field. Image: azergold.az

The mineral wealth of the Caucasus has been known for millennia. Quite apart from the Caspian coast’s oil and gas deposits, which have long given Azerbaijan its nickname ‘Land of Fire,’ the region boasts an astonishing range of metal ore sources. The area was so famed that Jason and the Argonauts headed to Colchis (part of what’s now Georgia) in search of the Golden Fleece— which was possibly a sheepskin that had been used to pan for gold in the rivers: gold flakes would stick to the wool but sand wouldn’t. Archaeologists have found apparent proof of gold sand processing in Western Georgia dating back to the early Bronze Age. Armenia has the richest concentrations of mineral deposits for its size, the most mine sites, and derives a considerable percentage of its export revenues from ore extraction. Close to the Georgian border, the Armenian province of Lori around Alaverdi has long been famed for its copper deposits which attracted Pontic Greek miners (from Anatolia) in the 18th century, later becoming the focus for a border conflict between newly independent Armenia and Georgia in 1918. Armenia’s biggest mining corporation ZCMC (Zangezur Copper and Molybdenum Combine), is one of the world’s top ten producers of molybdenum—an important additive for high-performance steel alloys (as well as being a fertilizer for cauliflower!)

Much of Azerbaijan’s non-oil mineral wealth is in the Lesser Caucasus, with gold at Gadabey and aluminum ore at Dashkasan. Moreover, several mining operations are in areas occupied by Armenia until the Second Karabakh War—notably Zod/Sokt, where the production area straddles the Armenian-Azerbaijani border with predictably problematic results. Georgia has limited mining these days though Chiatura is known for its manganese deposits.

The USSR left a “harmful legacy of environmental abuses,” which have proved particularly expensive to remedy. Post-Soviet governments had limited resources to fix such legacies or to upgrade polluting, out-dated industrial infrastructure and disposal procedures, such as the containment ponds for ‘tailings’ and contaminated wastewater. A lack of transparency over management structures made locals feel endangered by the lack of oversight that had long been a problem in preventing environmental contamination from mine operators. This has started to change in the last decade or so.

Back in 2015, the previous Armenian government committed to becoming compliant with the EITI (Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative) to bring the country to international standards in terms of ethics, honesty, open data, and civil society participation. However, according to a World Bank Report, the initial steps lacked substance, and it was really only after the Pashinyan government came to power that important strides were made. Progress has been mixed, but the decision to open up the industry to closer scrutiny has had several interesting effects. In 2018, rigorous inspections were initiated as part of the initiative, and certain mines—notably the new Lichk Copper Mine in the far south—closed rather than submitting to full checks[1]. In February 2018, the operation of a large copper-molybdenum mine near Teghut in Lori Province was temporarily suspended following a leak from its tailings dam into the Shnogh River.

In April that year, the same company’s major copper smelting works at Alaverdi were fined for its excessive sulphur dioxide emissions. Initially unable or unwilling to upgrade out-dated equipment, the copper production in Armenia’s ‘copper city’ ground to a halt, only restarting in 2022 once new, cleaner furnace technology had been fitted[2]. At least publicly, ZCMC’s sustainability statement now subscribes to the principles of “protecting our environmental surroundings” while trying to optimize shareholder value. The Teghut mine reopened in 2019 with a strengthened tailings dam and a reforestation project (later found to be partially fraudulent), and as of June 2023, the mining operation is due to be expanded, having passed an environmental impact assessment.

The EITI system has also opened up questions about the complex ownership structures of the nation’s many mining outfits. Although only resulting in partial disclosure, the press went on to give considerably more detail based on the clues provided by the initiative’s revelations. Armenia’s first EITI report was published in 2019, and as of June 2023, EITI currently rates Armenia as making High/Satisfactory progress. Notably, in 2022, a new rule has allocated 2% of royalties paid by seven major mining companies to be funnelled directly back to the 33 communities most affected by their operations.

Unlike Armenia, neither Georgia nor Azerbaijan have signed up to the EITI system—nor has the U.S., for that matter—making fair direct comparisons somewhat difficult. However, while neither country is as economically dependent on mining as Armenia, similar challenges apply in both. Anglo Asian Mining the most prominent operator in Azerbaijan, is British registered with a complex ownership structure that includes as a board member John Sununu, former chief of staff to U.S. President George H W Bush. Anglo Asian (or its subsidiary) operates the large gold mine in the grassy mountain foothills of Gadabey—a place where metal ores were first exploited by Siemens from 1865 to 1920.

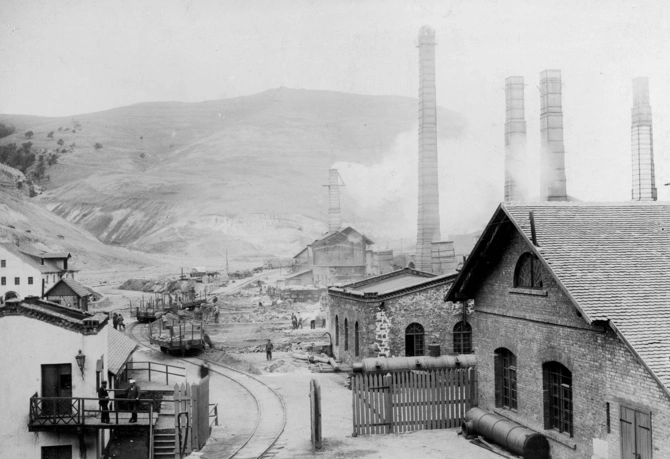

Gadabey’s copper works in the 19th century. Image: azerbaijantraveller.com

The most elegant of 23 stone viaducts built for mineral line trains to reach Siemens’ processing site at Galakent are now tourist sites in the region and one featured as a set in the 2016 movie Ali and Nino. In 1893, Siemens made a contract to sell its entire production of copper ores to the Nobel Brothers’ company in Baku, but they had also managed to extract some 3 tonnes of gold along with 52 tonnes of silver and ample cobalt before the company was nationalized by the Bolsheviks in 1920. Thereafter it fell into disrepair, so the Anglo Asian Gold Mine operation benefitted from a completely fresh start when it opened near Soyudlu village in 2009. Anglo Asian was thus able to design a production facility to modern specifications, including a massive tailings dam with a reed bed to deal with any potential leakage and, from 2017, an additional reverse-osmosis water treatment plant. However, a victim of its own success, these facilities had almost reached capacity in 2022 and plans to create an interim ‘auxiliary’ dam has run into local opposition, with villagers claiming that a local lake has already been poisoned by toxic waste leeching out of the tailings.

Image: tv.ikisahil.az

The situation caused international media interest in June 2023 when older, traditionally dressed village ladies were treated with unnecessary brutality by masked riot police, breaking up a small demo in the mountain pastures near the mines with tear gas and truncheons. Such was the outcry that Azerbaijan’s president, Ilham Aliyev, felt it necessary to castigate the Ministry of Ecology and Natural Resources which, he suggested, had been negligent or worse. While upholding villagers’ right to protest, Aliyev supported the police in their crackdown.

Police – and Russian peacekeepers – were contrastingly hands-off in Karabakh over another ecological protest that rumbled on between December 2022 and April 2023. In that case, with tacit official approval, Azerbaijani environmental NGOs demanded an end to unlicensed mining activities in the Armenian-controlled areas of Karabakh. The protest gained a lot of international exposure due to its limiting of travel along the one road that Karabakh Armenians use to reach Armenia proper. Those protestors claim to be concerned at the ecological effects of illegal mineral extraction by Armenians of copper and molybdenum from the Demirli (aka Kashan) site, a mining concession that is on paper signed over to none other than Anglo Asian Mining, operator of the Gadabey mines. The protest ended with Azerbaijani government installing a checkpoint at the border with Armenia essentially making it impossible to transport the resources extracted by the Karabakh Armenians.

Image: fed.az

Azerbaijan’s other significant mining operation is at Dashkasan, a functional Soviet-era city perched on a mountainside where a giant statue of a pick-axe-wielding miner welcomes visitors. Huge quarries for both marble and aluminum ore are all too visible, the latter an important source for the smelters at Ganja which had been mothballed for years but have been revamped since 2018.

One of the most visible features approaching Dashkasan is the curious series of ropeways for transporting large quantities of ore across the unforgiving topography. However, the classic place for such infrastructure is Chiatura, a manganese-mining city in Georgia. Developed in the Soviet era and now something of a honeypot destination for dark-tourism aficionados, it was the setting of the moving 2017 film City of the Sun. Built into a deep-cut gorge, the site once had no less than 17 cable-ways forming a network amid the cliffs and depressing tower apartments. The network included infamous ‘metal coffin’ cable-cars used by people to get around and to access hill-top mine sites. In 2021, four key routes were reopened, having been rebuilt to contemporary safety standards to avoid potential catastrophes, but some of the 1950s originals are set for preservation as historic monuments. However, that doesn’t mean the local ecology has been similarly rescued. The manganese deposits, first discovered by a famous Georgian poet in 1879, remain very valuable and exploitation continues apace by Georgian Manganese (GM). Their website describes the company as one of the nation’s biggest industrial employers but has no sustainability statement despite GM agreeing back in 2017 to have an environmental audit. The company, whose ultimate majority share ownership appears to be a Ukrainian billionaire, has faced various accusations over worker safety, tax irregularities, lack of transparency, and appalling environmental damage. On top of this, workers were given demands in 2023 to up production by 40% in quotas described as “inhuman,” leading last month to an 18-day strike, plus a march and hunger strike which finally led the company to back down.

Mining can be a major political issue. Azerbaijan is still smarting from the fact that many of the mineral resources of Karabakh were exploited by Armenia during the decades under which the region was under occupation. And pollution caused by poor mining practises can have a transnational impact with toxic waste leeching into rivers and water sources that cross boundaries. Just last week, an open letter to the Armenian PM, signed by representatives from 24 Azerbaijani NGOs, cited several cases in which Baku believes that Yerevan could reduce the environmental pollution that goes beyond its national borders.

Meanwhile, as noted above, eco-activism and operational transparency, are important strands in the push to ensure that mining benefits society in general not just the production companies (and the state coffers through taxation). Mine tailings and toxic discharges will inevitably continue to be a problem in the environment, but awareness and public pressure will hopefully keep encouraging improved standards that will eventually be to the benefit of all. In Azerbaijan, Eco Front is a small but passionate outfit that helps raise awareness of environmental abuse. Armenia’s Ecolur is a bigger organization which works with others to publicize the monitoring of chemical pollution created by the industry and its effect on public health. And in Georgia, Green Alternative works hard to monitor stories about mining and industrial abuse of the environment as well as more general themes of climate change.

[1] Plans to reopen the mine in April 2023 have led to protests from residents afraid of serious environmental problems.

[2] Though heavy metal deposits in nearby rivers are still showing unacceptably high sediments of heavy metals from historic contamination

Share on social media