Georgia's link to Europe is more ancient than most people think. Alexander Davitashvili analyzes the events that formed the country's current ambition to join the EU.

June 20, 2022. Tens of thousands of people gathered in the centre of Tbilisi to show their support for Georgia to join the EU and, eventually, the 27-nation bloc. Image: Reuters video screengrab

In previous articles about Russo-Georgian relations, I have tried to show that the South Caucasian country is geopolitically “off the table” to the looming presence of Russia on its northern borders. But Georgia’s strong self-image is far more than just a reaction to its powerful Slavic and Turkic neighbours: there is also a deeply ingrained sense of ‘European-ness’ in the national character. This message was underlined recently by the large protests in the capital, Tbilisi, when over 100,000 people gathered to demand the government’s resignation when Georgia failed to obtain EU candidate-member status. It felt all the more galling, given that Ukraine and Moldova were successful. Back in 2019, these three countries had been seen as the so-called “Association Trio,” pursuing a European future with a united effort. However, in the end, Georgia was left behind – and many blame controversial statements and steps made by the Georgian government and its ruling party, Georgian Dream. The European Council has nonetheless acknowledged Georgia’s European Perspective and given 12 recommendations. But what makes Georgians so passionate about being part of Europe from a political and civilizational point of view?

Geographically, the country is the furthest from the EU aspiring for membership. Here in Georgia, from elementary school onwards, we are taught that we are at the intersection of Europe and Asia and that our homeland is a fusion of cultural influences. However, within this, the idea of ‘European-ness’ is paramount. Back in 2000, then President Eduard Shevardnadze told German journalists that “according to new studies, the first Europeans were living in Georgia 1.7 million years ago, now I’m travelling to Europe and telling them that you are our heirs.” It was a slight misquote based on a scientific article in the Journal of Human Evolution which cited Dmanisi Man as “the oldest population of hominins known outside of Africa.” But it underlined the deep belief that permeates the Georgian psyche that Georgians are Europeans – perhaps the original Caucasians in a very literal sense.

The history of Georgia as a nation goes back around 3000 years, but it’s worth mentioning that in the beginning, it was, in fact, two connected countries. Western Georgia, aka Colchis (Egrisi/Kolkheti in Georgian), was probably founded around the sixth century BC, while Eastern Georgia, aka Iberia (Kartli in Georgian), was likely founded around the third century BC. Both of them had extensive relations with western civilizations.

Colchis is well known from Ancient Greek mythology thanks to the legendary journey of the Argonauts, a tragedy written by Euripides. In the legend, still very popular in Georgia, the Argonauts’ leader Jason falls in love with Princess Medea, daughter of Aeetes, King of Colchis. Medea was supposedly renowned for her medical abilities; some even claim that the word medicine derives from her name. In the tragedy, Jason ends up stealing both Medea and the famous “Golden Fleece” from Aeetes. There are different theories in Georgia about what the Golden Fleece represents. Some believe it was a technical tool of gold production, and some scholars believe it was an artifact from sheep farming culture. However, there is no factual explanation of what the Ancient Greeks took from Colchis. The second part of Euripides’ story is neglected in Georgia as it shows the darker side of Medea, who finds out that Jason is unfaithful and kills their children in revenge, considering that the best way to hurt him. However, on a more positive note, it’s worth mentioning that in another Ancient Greek myth, King Minos of Crete was married to Pasiphae, sister of Aeetes. Clearly, Colchis was far from being peripheral to the culture of Mediterranean Europe at this time.

A monument to Amriani, Georgia’s “Prometheus,” in east Georgia. Image: khalampre/Wikimedia Commons

Indeed, the interconnection of Georgian and Greek mythology goes even further. Prometheus is remembered as the Titan who stole fire from the gods and gave it to humankind. But did you know that he has a Georgian doppelganger called Amriani? The story is very similar; both were punished and chained to the Caucasus Mountains.

In terms of less mythical relations, the first historical interaction between Georgia and Ancient Greece started when Greek colonization expanded to the Black Sea littoral. Georgia’s location made it useful as an entrepot for trade with Asian countries via the Silk Roads. Consequently, Georgian archeologists often find artifacts from a wide range of ancient cultures, both eastern and western. Greek influence was later replaced with that of the Romans and Byzantines, which was more complicated, with more aggressive efforts to control Georgia. Accepting Orthodox Christianity in the fourth century further encouraged Georgia to look westward culturally. For much of the next century, the Georgian church was under the control of the Byzantine Patriarch, but after King Vakhtang Gorgasali liberated Iberia from Persian occupation in 484, the Georgian Church received autocephaly and became independent.

Between the 9th and 11th centuries, Georgians played a major role in the Byzantine Empire, with both Georgians and Armenians holding high military positions in the imperial army. Despite the fact that Byzantium tried to use aggressive military force on Georgia from time to time, relations were primarily peaceful.

The Seljuk Empire later occupied Georgia, but King David IV, “the Builder,” managed to regain independence with the 1121 war that culminated in the Battle of Didgori. For the first time, eastern and western Georgia were united. David used the opportunity of the Crusades to forge partnerships with fellow Christian western powers, and Georgians were ready to participate in the fifth crusade. However, events were soon overtaken by the invasions of the Mongols, which completely re-drew the geopolitical landscape during the 13th century and left Georgia divided once again, often under foreign suzerainty.

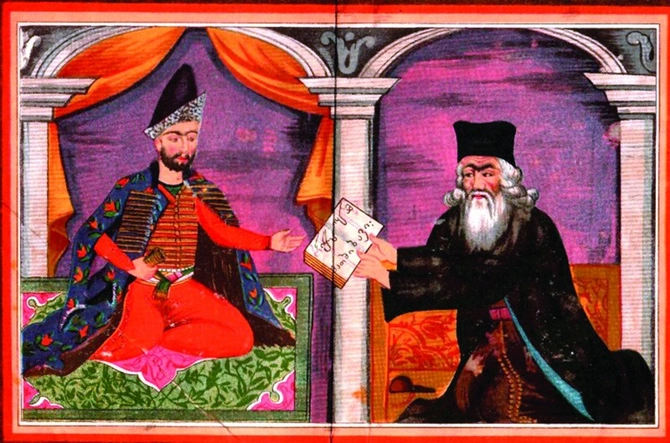

Vakhtang VI of Kartli and Sulkhan-Saba Orbeliani are featured in an 18th-century miniature. Image: Wikimedia Commons

Fast forward to the 18th century for an epic story of Georgian diplomat and educator Sulkhan-Saba Orbeliani, uncle and teacher of King Vakhtang VI of Kartli (eastern Georgia). Orbeliani was a great polymath who published the first Georgian dictionary and the first set of documents showing how Georgia’s legal system united foreign and local practices. Sulkhan-Saba came out of monastic seclusion to undertake a remarkable journey on behalf of his nephew. It took him to many key places in Europe, seeking assistance for Georgia against the Ottoman Turks in what is now remembered as the first direct declaration of semi-modern Georgia’s desire to be part of European civilization. In Rome, Pope Clement XI was said to have treated Orbeliani as “the Father of all Georgia.” Before that, he had visited France in spring 1714, meeting Sun King Louis XIV on several occasions. They discussed establishing military and trade relations, the development of Tbilisi as a logistics hub and the possibilities of spreading Catholicism in Georgia. The talks went well, but for practical purposes, the Orbeliani mission was initially kept secret, and the shelved proposals were eventually forgotten once Louis died a few months later. After that, France instead chose to maintain relations with the Ottoman and Persian Empires rather than support an autonomous Georgian kingdom.

For the following centuries, relations with European countries were limited, and in 1783 the Treaty of Georgievsk essentially extinguished Georgian independence by starting the country’s absorption into Russia.

It was not until 1918 that Georgia managed to regain independence, and even then, only for three years. In the period leading up to the declaration of this independence, Georgia was home to a huge pro-Western movement called the “Society for Spreading Reading and Writing.” It was chaired by the prominent writer and philanthropist Ilia Chavchavadze, who had also reformed the Georgian language. Another of the leading figures was Iakob Gogebashvili, who introduced the first (massive) Georgian language handbook Deda Ena (Mother Language), which presented a Georgianized version of Western European study methods.

The Bolshevik Red Army in Tbilisi, February 25, 1921. Up on the hill, Saint David's Church is visible in the distance. Image: Photomuseum of Georgia/Wikimedia Commons

The short period of independence from 1918-1921 deserves an article in its own right, but it’s worth mentioning here that the political elite back then was undoubtedly inspired by European social-democratic ideologies. Georgia introduced a very progressive constitution whose many interesting initiatives included voting rights for women. Five of the National Council’s 130 members were women, unprecedented at that time, even for European politics. Embassies were fully functioning in Germany and Sweden. On February 25, 1921, the Georgian ambassador delivered his credentials to the President of France on the very day that Russia’s Red Army crushed Georgia’s independence. France would later offer asylum to Georgia’s government in exile at a chateau estate 37km south of Paris. But, it would not be until the collapse of the USSR in 1991 that Georgia would finally gain its independence long term.

Throughout history, Georgia has passed through hellfire in its struggle for independence and to retain its Euro-centric mindset. The country has been occupied many times, a desire for freedom was kept alive, and it finally managed to liberate itself. Being at the crossroads of Europe and Asia affected the formation of the Georgian nation and created a unique set of values that take elements from both continents. The empires surrounding the Caucasus region have a history of creating an unstable environment for development, and Georgian leaders have often had to make difficult choices between big international players. These choices have at times been based on religious factors, but today, as Georgia once again reaches such a crossroads, the difference is more one of ideology. On one side, there is the European Union, seen as a flagship of democracy and freedom. On the other side is Russia, perceived as a restrictive autocracy. This year the streets have been filled with people communicating what they want for their country, and now it’s up to the political elite to set aside their differences and work together to implement the nation's will.

Share on social media