Among the many ethnolinguistic communities in Azerbaijan, we find the Udi people of Nij. Considered to be the descendants of the ancient Caucasian Albanians, they speak a language indigenous to the Caucasus. What can we know for sure of the group's history?

Image: AnarAliyev/Shutterstock

Well-spaced houses hidden in green gardens and hazelnut orchards form the outwardly unremarkable rural village of Nij village, around 20km west of Qabala, Azerbaijan. However, within its maze of winding lanes lie no less than three historic churches. This place is culturally unique in that its population is around 65% Christian Udi, an ethnic group whose language is the closest remaining living link to that of the Caucasian Albanians.

For real Udi food, the outwardly dowdy Əjdər Restaurant in Nij is one of the finest places in Azerbaijan for organic pork kebabs served with tart sour plum sauce. Muç’a! (‘delicious’ in Udi).

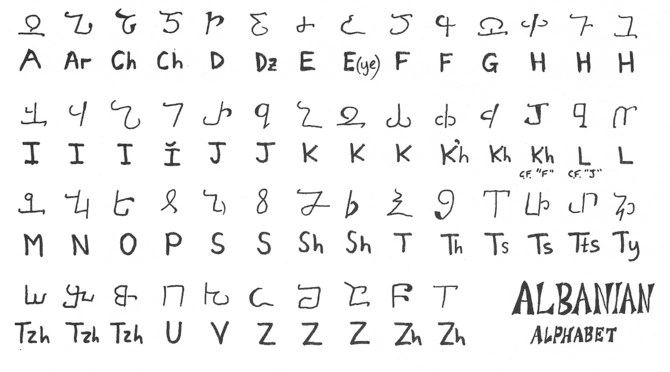

Theirs was a long-lived kingdom that covered much of the same territory that we now know as Azerbaijan. In 313 AD, Albania’s King Urnair was one of the world’s first monarchs to adopt Christianity – Armenian and Georgian rulers also converted in the same century. A Caucasian Albanian language became the lingua franca of the Eastern Caucasus during the 5th century. It had a written script of its own that was primarily used in Bibles and bureaucratic documents but started to fall out of use in the 8th century. That was mainly because significant populations of Albania were converted to Islam following the Arab invasions and later waves of Turkic migrations. By the 15th-century, the Caucasian Albanian script was essentially ‘lost.’ Or, so it was thought until the early 20th century when archaeologists found inscriptions in a mysterious alphabet. Then, in 1996, palimpsests (recycled parchments) were discovered at St Catherine’s Monastery on Mount Sinai (now Egypt). Beneath the Georgian writing of the surface layer was an older document in the same mystery script, which researchers realized must be the long-lost Caucasian Albanian. With painstaking research, it became possible to figure out the original 53-letter Caucasian Albanian alphabet.

Image: Mark Elliott

Back in 2001, it was largely a hunch that at least one of several now-lost Albanian language variants was linked to Udi. For two decades, however, linguistic scholars Wolfgang Schultz and Jost Gippert have made intense studies of the similarities and differences between the Caucasian Albanian language of the palimpsests and that of the Udis living in Nij. By 2015 Schultz could declare that Caucasian Albanian “can be regarded as a more or less direct ancestor of present-day Udi.”

This has been a remarkable piece of academic detective work, in some ways outshining even the deciphering of the Rosetta Stone[1]. However, it has also focussed considerable attention on the small community of Nij and its history.

By the 11th century, the Albanian Church was withering, but Nij remained one of its last spiritual centres. Until 1836, churches here still held Albanian-Christian masses, but by that time, there were so few other Albanian-Christian communities that Tsarist Russia saw little reason for the church to remain autocephalous[2]. Thus the synod of St Petersburg, by putting the Armenian Catholicos[3] as head of all Gregorian Christian groups within the empire, essentially merged the Albanian and Armenian churches. This required the Udi clergy to follow Armenian rites, and Armenian inscriptions were added to some church buildings. In reality, some Nij citizens quietly carried on their own ways. According to one story, when the anti-religious USSR banished the village’s last pastor to Siberia, he faked his own death with the cooperation of the then-mayor of Nij and for a while went on preaching surreptitiously. Later in the Soviet era, the church buildings were left to decay due to the lack of official funding, but locals continued to ‘secretly’ place candles and votive cloth strips on doorways and carved stones in a clandestine continuation of their faith.

Image: Mark Elliott

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, independent Azerbaijan has been keen to support the Udis’ Christian identity. The oldest of the churches was fully restored in 2006, and an Udi gentleman studied in Ukraine to become a priest for the re-consecrated site. High-profile international visitors to the church have included Thor Heyerdahl, Gerard Depardieu and the UK’s Prince Andrew, while, since the 2020 war, members of the Udi community have themselves been amongst delegations visiting ancient churches in de-occupied regions.

Their support by the Azerbaijani state is held up as a badge of the country's religious tolerance. However, at the same time, some prominent Azerbaijanis espouse the view that, because many of the country’s ancient churches were originally founded as Caucasian Albanian places of worship, any later use by Armenians suggests some sort of falsification of history. The reality is that even before 1836, very few Albanian Christian worshipers remained outside Nij and Vartashen (now known as Oghuz).

In any event, no matter the political sensitivity imposed on the group, the survival of the Udi language and culture is historically remarkable and well worth celebrating.

See our video about the Udi community here.

[1] The Rosetta Stone unlocked the reading of ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs

[2] i.e., an independent Christian denomination with its own hierarchy. Russia had already abolished the autocephaly of the Georgian church in 1811.

[3] equivalent of pope in Orthodox Christianity

Share on social media