Uzbekistan is ever more popular with tourists thanks to its trio of majestic Silk Route cities, Samarkand, Bukhara, and Khiva. But what about the far west of the country? Mark Elliott heads to Nukus, the capital of Karakalpakstan.

All images by Mark Elliott

Though little known abroad, the western third of Uzbekistan forms the Autonomous Republic of Karakalpakstan. That’s the sparsely populated home to the Karakalpak people, who celebrate their own proud history and speak a Turkic language that often seems closer to Kazakh or Azerbaijani than to Uzbek. The region is vast, but even for those who can find it on a map, it’s most likely that they will associate the region with the ecological catastrophe of the Aral Sea, or perhaps last year’s brief flicker of popular unrest when Tashkent toyed with the idea of removing the republic’s autonomy. The idea was swiftly dropped when the strength of the opposition was understood.

So before visiting the capital, Nukus, I’ll confess that my image of the place was entirely incorrect. I guess I had imagined a dowdy, desolate little Soviet backwater of tumble-down apartments and a general air of depression amongst people breathing in salt-dust from the desiccated Aral seabed. What I found was a remarkably relaxed modern city. Far from being a small town, the population tops 300,000, and the city centre is home to some surprisingly suave cafes and restaurants—even if one of them has unadvisedly decided to name itself Cake Bumer.

One of the nights I was in town, the family atmosphere was greatly amplified by a large celebration for International Children’s Day—free concerts for kids of all ages, light shows, and fireworks, along with lots of people on the streets once the full blasting heat of the day had subsided.

The main stage was set on the square that fronts the Savitsky Museum, perhaps the place in Karakalpakstan I had been most excited to see. For art lovers, the Savitsky has something of an international cult following, a mythical gallery that many dream of visiting though few actually make it this far. Instead, the art world simply scratches its head, wondering how on earth the Savitsky somehow managed to amass the world’s second biggest collection of Russian Avant Garde paintings. According to the merrily repeated story that this was due to the sheer remoteness of Nukus as a distant backwater: being so far from the powers that be in Moscow or Tashkent, nobody prevented the museum from keeping works that would have been considered ‘degenerate’ elsewhere in the USSR and destroyed for not sticking to the imposed strictures of Soviet Realism.

Listening to museum guides, I realized that the tale is only half right and the gallery’s story is rather more nuanced.

By any standards, the museum is an impressive place with some 100,000 items in the permanent collection, 80% of them collected during the tenure of its eponymous founder, Igor Savitsky (1915-1984).

The Ukrainian born Savitsky originally came to Central Asia as a painter to record the work of archaeologists exploring the region’s remarkable wealth of pre-Genghis Khan antiquities[1]. So, I shouldn’t have been surprised to find that the museum has a rich selection of ancient artifacts along with plenty of valuable ethnographic pieces.

These augment a detailed, if scattergun, introduction to the history and culture of the Karakalpak people, a theme that continues in considerably more detail at the separate, if nearby, History Museum[2].

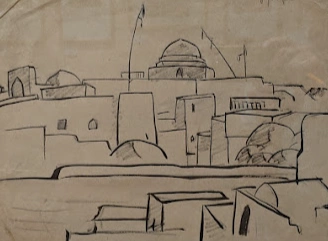

Guides are keen to tantalize visitors, delaying the moment at which one arrives at the avant garde paintings by lengthy introductions to Savitsky, his early sketches and his teacher, Aleksander Volkov (1886-1957), whose cubist-inspired work was declared an anti-revolutionary in the mid-1930s.[3]

Volkov’s 1928 Chaikhana hoped to win over the censors by popping a portrait of Lenin in the background.

The inter-relationships between the various eclectic artists who found themselves in Soviet Central Asia is also an interesting theme.

One of the great unsung highlights of the gallery is the rich collection of 20th-canvasses of Uzbek scenes by talented, if somewhat lesser, known artists.

For me, one of the most mesmerizing paintings in the collection is the 1934 view of the Brich Mulla Valley by Ural Tansykbayev (1904-1974), an ethnic Kazakh who spent much of his life in Uzbekistan. French expressionists and Fauvism influenced his early work.

Tansikbayev’s Aral Sea Fishermen (1936)

He would later edge towards the safety of Soviet realism as well as becoming a costume designer, a move which allowed him to live through the Stalin purges and on, years later, into retirement. He died in Nukus.

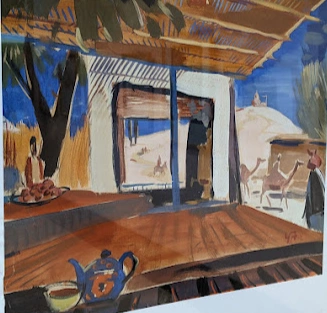

A fellow early expressionist and rough contemporary of Tansykbayev was Victor Ufimtsev (1899-1964), born in the Urals but becoming naturalized in Uzbekistan. He set off from Russia with a futurist vision of art demanding a new form but also took inspiration from the scenes of Central Asia, which he saw as “one big carnival.”

Ufimtsev played cleverly with space creating optical illusions as with To the Train, a part collage using cloth and sand on a non-rectangular canvas and uses shapes and scales to great effect.

Ufimtsev’s Chaikhana in Chagatai, 1947

More recent Uzbek art is also featured, including some splendid work by Jeńis Lepesov (b 1945) and plenty by Uzakbergen Saparov (1943-2008), said to have been one of Savitsky’s favourite students. He was nicknamed “Goganbey” due to the perception of a Gaugin-like element in many of his paintings.

Jeńis Lepesov’s Portrait of a Girl (1970)

However, it’s inevitably the avant garde and expressionist art that continues to be the main attraction. A key part of Savitsky’s collecting was that he had very close personal connections with artists across the USSR and with their families too. Thus he was able to source paintings that had been kept hidden for decades through the 1930s repressions and again during the late-Stalinist attacks. Preserved from censorship—or worse—these gems only really started being unveiled in the later Khrushchev era, by which stage attitudes had softened, with Savitsky by then a mainstay of local society in Nukus with strong connections to party officials.

Some paintings had only survived in fragmentary form. An example is the rather nightmarish canvas titled Capital (1931) by Mikhail Kurzin. Despite being an apparently clear commentary against the excesses of capitalism, it was frowned upon once Kurzin himself became accused of formalism and anti-Soviet sentiment leading to a five-year jail sentence in 1936.

Guide, Sabina, explains the story of Kurzin’s 1931 Capital of which only the upper part has survived

Vladimir Komarovsky (1889-1937), one of the early Russian avant garde artists, painted this self-portrait in the 1920s: in fact it’s a two-sided affair on board with a family group on the reverse.

A 1920s self-portrait by Vladimir Komarovsky (1889-1937) shows him with a staring expression that, according to some readings, hints at the artist’s precarious mental health condition. However, a degree of preoccupation can hardly be seen as surprising for a man who had been born noble but lost his estate to the Bolsheviks, later being arrested twice in the 1920s—on one occasion only getting out of trouble when vouched for by Trotsky’s wife who respected his talents. In the end, he was shot in 1937, sentenced to death during Stalin’s purges, ostensibly for following an un-sanctioned religion.

Museum staff consider the star canvas to be Vasili Lisenko’s semi-abstract Bull.

Bull by Vasili Lisenko 1899-1975

The artist claimed it was a critical allegory of the advance of fascism, but it still didn’t please the Soviet style police. Even once it had been installed in the early museum, Savitsky was told to take it down by inspectors that considered it un-Soviet. As the story goes, Savitsky obeyed, but as soon as the outsiders had left he put it back up again.

Somehow, it’s a story that sums up the whole museum, if not the city—a place that somehow just keeps bouncing back with positive energy and a gentle exuberance that can’t be extinguished.

[1] The once great empire of Khorazm had made the fatal geopolitical error of attempting to stand up to the Mongols in 1220.

[2] Officially going by the unwieldy name of “The State Museum of the History and Culture of the Republic of Karakalpakstan.”

[3] Volkov was briefly rehabilitated during WWII and became a ‘People’s Artist’ in 1946 before the mood swung against him again, with Moscow demanding that the Uzbek SSR’s Union of Painters isolate him from contact with other painters or critics.

Share on social media