Photo credit: Youtube screenshot

By Tural Heybatov

By turning rivers into instruments of coercion, India is not only aggravating its conflict with Pakistan - it is undermining decades of fragile regional stability.

“We are working on short-, medium-, and long-term measures to ensure not a single drop of water flows into Pakistan,” India’s Minister of Water Resources, Chandrakant Raghunath Patil, recently declared to reporters. These words are not just provocative rhetoric - they signal a strategic shift in India’s approach to water diplomacy, one that could usher in a dangerous new era of geopolitical confrontation.

Last week, India formally announced its unilateral withdrawal from the 1960 Indus Waters Treaty - an agreement signed with Pakistan under the mediation of the World Bank. This treaty, despite numerous wars and political crises, had stood as a rare symbol of cooperation between the two nuclear-armed neighbors. Islamabad has already warned that India’s actions could be interpreted as an act of war. Yet New Delhi appears undeterred.

Both India and Pakistan suffer from chronic water shortages. But India now seems poised to exploit its geographic position as the upstream power on the Indus River system to deprive its neighbor of vital resources. And the recent developments suggest that this is not a hypothetical threat.

Photo: Daniel Berehulak/Getty Images

On April 27, The Times of India reported that India had released a sudden flow of water into the Jhelum River - a major tributary of the Indus - without any prior warning. The release originated from the Uri Hydropower Dam and caused a sharp rise in water levels in the Pakistan-administered part of Kashmir. The resulting flood forced the evacuation of entire communities in the Hattian district. Villagers reported that the water came without warning, leaving them with no choice but to flee with whatever belongings they could carry, abandoning crops and livestock. There are already reports of agricultural damage and animal deaths.

According to international norms and treaty obligations, India was required to notify Pakistan in advance of any water release - particularly one of such magnitude. It failed to do so.

Water blackmail is not a new tool in asymmetric conflicts. During its occupation of Azerbaijani territories, Armenia - situated upstream of several rivers flowing into Azerbaijan - regularly cut off water supplies or, during periods of snowmelt and flooding, released large volumes of water, inundating agricultural lands. India is now employing a similar tactic.

Despite Minister Patil’s strong statements, experts argue that India currently lacks the technical infrastructure to deprive Pakistan of water entirely. Massive dam networks, expansive canal systems, and sophisticated storage facilities would be required to execute such a strategy effectively - and India does not yet have them. The real danger, however, lies in New Delhi’s ability to manipulate water flows during critical periods: reducing access during droughts and releasing torrents during flood seasons.

The 1960 treaty had divided the Indus basin into two parts: the eastern rivers - Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej - were allocated to India, while the western rivers - Indus, Jhelum, and Chenab - were given to Pakistan, which depends on them for 80% of its water needs. Only 20% of the western rivers’ water was allocated to India. This division, while imperfect, ensured a degree of predictability and cooperation over a shared resource. India’s abandonment of the treaty could now destabilize this fragile balance.

According to Climate Diplomacy, Pakistan is among the countries most vulnerable to climate change-driven water stress and flooding. Under the treaty, India is obligated to share hydrological data with Pakistan, vital for flood forecasting, irrigation planning, and ensuring drinking water reserves. Now, Indian officials are signaling a potential end to this cooperation as well. As former Indus Waters Commissioner for Pakistan, Shiraz Memon, recently told the BBC, India had already been sharing only about 40% of the necessary data.

While India cannot currently eliminate Pakistan’s water supply, its ability to weaponize timing - to open floodgates or close off flow during strategic moments - remains a powerful lever. The events of April 26 are proof.

As the BBC notes, India simply does not possess the storage or diversion infrastructure to hold back tens of billions of cubic meters of water from the western rivers during peak flow periods. Ironically, India isn’t even capable of fully utilizing the 20% water allocation granted under the treaty. Indian hydrological experts admit that their country’s outdated and insufficient water management systems are a major constraint - and cite this as a justification for the construction of new reservoirs and dams. Pakistan, however, strongly opposes such projects, pointing to the treaty's restrictions.

As Hasan F. Khan, Associate Professor of Urban Environmental Policy and Planning at Tufts University, wrote in Dawn, the most serious consequences may emerge during the dry season, when water levels fall, timing becomes critical, and the absence of treaty safeguards could be most acutely felt.

India’s ambitions around water must also consider an often-overlooked strategic reality: New Delhi is itself downstream from China on both the Brahmaputra and Indus Rivers, which originate in Tibet. In 2016, following India’s provocative statement that “blood and water cannot flow together” - made in the wake of a militant attack in Indian-administered Kashmir that it blamed on Pakistan - China responded by blocking the Yarlung Tsangpo River (which becomes the Brahmaputra in northeast India). Although Beijing claimed it was related to a hydropower project, the timing sent a clear political message.

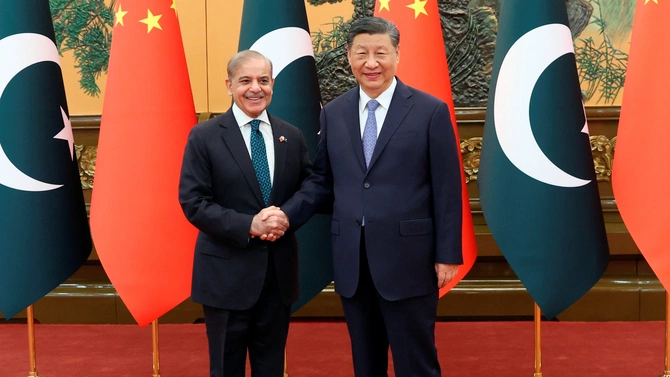

Chinese President Xi Jinping and Pakistani Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif shake hands at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing on June 7, 2024. © Reuters

China is a close strategic partner of Pakistan, and while its moves in 2016 may have seemed limited, they were enough to remind India that in the dangerous game of water geopolitics, it, too, can be vulnerable.

New Delhi’s current strategy - abandoning a landmark treaty, withholding data, and releasing water without notice - amounts to a deliberate escalation of tensions in one of the world’s most volatile regions. If India continues down this path, it may not only provoke a humanitarian crisis in Pakistan but also trigger broader geopolitical blowback from China, from international institutions, and from other regional powers.

The world must take this seriously. Water wars were once considered a dystopian future. India is making them a present reality.

Share on social media