Now that the fighting is over - can advances in technology be a missing piece of the puzzle for Azerbaijan and Armenia to move forward?

The owner of a local bakery in Shusha, Azerbaijan. July 4, 2021. Large-scale construction and restoration of infrastructure facilities are underway at the territories of Nagorno-Karabakh that passed over to Azerbaijan after the 2020 conflict with Armenia. Gavriil Grigorov/TASS

Advances in technology have changed our lives significantly. They affect how we interact with each other, how we respond to each other’s actions and how we report and cope with emergencies. Information and communication technologies help us share information about violence and criminal activities. Brave journalists have put their lives in danger for the sake of giving the rest of the world a clearer picture of events in war zones.

Thirty years on, things are very different. Internet and social media mean that we are able almost instantaneously to observe world events. We see both horrors and moving stories of resilience, like what Afghans are going through to save their families from Taliban forces. We can witness nearly in real-time the bravery and compassion of those who save others from violence and give them hope for a new life. Technology can work both ways, too, not only helping us to remember key moments of warfare but also as a tool to build and sustain peace between hostile communities.

According to a 1992 UN report, peacebuilding is “action to identify and support structures which tend to strengthen and solidify in order to avoid a relapse into conflict.” Academic research by Paul Collier[1] and others suggests that about one-third of conflicts re-ignite within ten years of a ceasefire. The existence of peacekeeping operations and economic development are identified as two significant factors to improve this statistic and to achieve sustainable peace. In the Karabakh context, Russian peacekeeping operations along with both countries’ national forces have been able to restore approximate stability after the 2020 war. But ideally, peacekeepers should operate with a deadline, and true peace can only come when the region becomes stable without them.

To sustain long-term economic development in the area, both sides need to start engaging in trust-building efforts. Research shows that minorities tend to underinvest in public goods because they lack confidence in public institutions ruled by the majority. This complicates gaining a minority’s confidence, especially when both sides have a history of conflict, as in the case of Armenians within Azerbaijan.

Before the USSR collapsed, Azerbaijanis were a minority in Armenia, just as Armenians were, and still are, a minority in Azerbaijan. Azerbaijani authorities would like to see Armenians live in Karabakh under Azerbaijan’s rule but simultaneously demand that Armenia allow Azerbaijanis to go back to the homes in Armenia that they left during the late 80 s.

So how can new technologies help with confidence-building between such previously hostile communities where trust is almost non-existent?

Let’s look back just over a decade to the global financial crisis in 2008. At that time, the crisis led to a significant loss of trust in public institutions, exacerbated by the dissemination of disinformation, along with the abuse of information technologies. Since then, new systems have emerged to engender faith between parties without requiring the involvement of a central authority. The most important of these is blockchain. Best known as the facilitator of crypto-currencies, blockchain technology essentially replaces a need for a third party to establish mechanisms in which two entities co-operate, ensuring compliance with the rules (or codes) of an agreement. Blockchain is a distributed ledger system that records chained ‘blocks’ of transactions in an immutable and transparent way that needs to be validated by decentralized peers. These blocks are linked to each other such that changing any one block would require a change in the entire chain. As a result, the rules of transactions are often made into smart contracts without the need for human intervention.

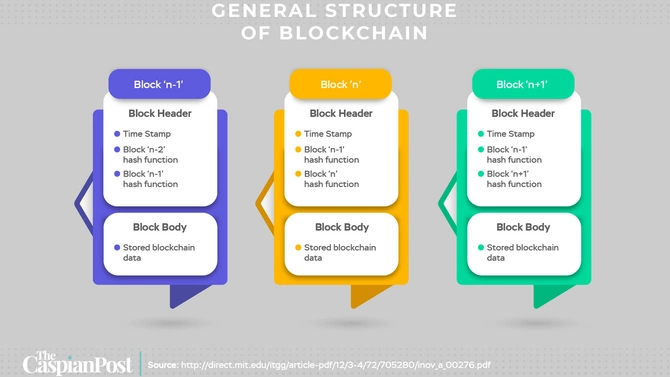

Each blockchain is a “chain of blocks” that stores data on transactions between different parties. When data is added or altered, a new block is added along with a timestamp and a ‘hash function’ linking the block to the previous block. ‘Hash functions’ are random inputs of data as a string of bytes, each with a fixed length and structure. Any attempt to change data has to be validated by all the participants in a public blockchain. If the data in a block is revised by malicious attacks, however, the corresponding hash function will change and will not match the function that is stored in the next block. That will flag the transaction as suspicious, and so the changed block will not be able to add itself to the chain. This makes blockchain more secure and resistant to potential attacks.

There are several layers and types of blockchain platforms, ranging from full public platforms to permissioned platforms by a public or private entity. In public platforms, anyone can take a read-only or edit role to make changes, add new blocks or maintain a full copy of the entire blockchain. In contrast, permissioned platforms prefer more security and identification and therefore allow special nodes to be seen by either all the participants or by select participants. Permissioned platforms are, in general, maintained by private organizations. It is also possible to organize things such that blockchains that are open to public scrutiny also have associated side-chains accessible only to selected parties.

Essentially, blockchain technology has the opportunity to build confidence between even the most implacably distrustful enemies, thanks to the three-pronged advantages of its cryptography, governance, and computational structure. First, because blockchain achieves a distributed consensus, it partially, if not wholly, solves the trust problem, building confidence via participation. Also, the process is less prone to cyber-attacks than most traditional systems as information is decentralized rather than held in cloud-based systems.

There are two particularly important areas in which blockchain can be applied to gain the confidence of communities in a post-conflict situation: land ownership and resource management.

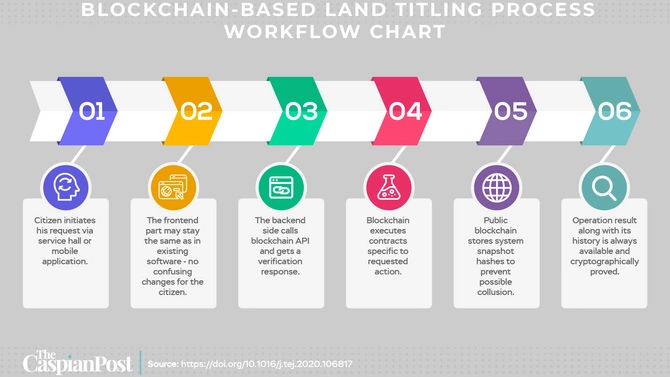

One of the most sensitive issues in conflict zones is that of land and property, ownership of which might be claimed by both parties. Such ownership can be made more transparent by ensuring that registry records of land and property ownership are digitized and recorded in a digital ledger accessible by all relevant stakeholders, with all stakeholders automatically notified about any attempted ownership transfers. A joint committee of representatives from Armenian and Azerbaijani communities would need to work together to manage the process. But once created, such a blockchain registry system would help build trust in public institutions, improve lending markets and boost the real estate sector in the former conflict region. Hopefully, it would eventually lead to real estate transactions between Armenian and Azerbaijan communities as a first step to building direct and/or virtual interactions between the two communities. This is by no means an impossible goal. Indeed, neighbouring Georgia is already one of the leading nations to successfully implement blockchain applications in its land registry.

Another area of conflict between communities is the fair, transparent use of energy and water resources. Modern technology can help here too. Both Armenian and Azerbaijani communities are now racing to control these resources in the de-occupied areas and around the borders between the two countries. For example, the biggest Armenian-majority city in Azerbaijan, Khankendi (Stepanakert to Armenians), has been suffering from both energy and water shortages. Meanwhile, Azerbaijan’s aspirations for re-building a large industrial and agricultural hub in the recently demined former ghost-city of Agdam desperately require a sustainable water supply. Both communities could choose to fight endlessly over the same natural resources, or to co-operate through innovative and trust-building approaches aimed at an optimal win-win sharing of them. A suitable system could improve distribution and security for infrastructure systems and potentially create space for trading excess supply among the communities. Suitable blockchain-based platforms would enable community leaders and public institutions to jointly track energy and water consumption, and prevent leaks and waste, ensuring a transparent use record. Smart data collection systems could also monitor water quality while accurate metering would improve financing options.

Blockchain technology needs to be at the heart of Azerbaijan’s aspirations of building smart communities. It can be applied not only to smart water and energy infrastructure but also to healthcare, education, financial systems and supply chain logistics. The various public and private institutions, plants and facilities could be brought together under one blockchain platform transparently and securely. This would not only improve quality and performance but also connect communities around better-governed structures.

But make no mistake, blockchain is no magic potion. Peace will not come without a final commitment from both sides to respect each other’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. A critical step in that direction is the agreed demarcation of the border between Azerbaijan and Armenia. A clearly defined, mutually accepted border is the starting point from which to build healthy direct relationships between the countries. Here too, modern technology is key. Geospatial tools, image analysis, and filtering techniques provide us with a set of tools to gather and process spatial information more accurately. Analogue images from the cartographic representation of international boundaries taken from treaties during the Soviet rule have been transferred into a digital format and are now being applied on the ground. After that, re-opening transportation routes will better connect communities living across the borderline to forge a better future.

[1] Collier’s theory of ‘conflict traps’ has been cited by world leaders including former UN Secretary General Kofi Annan

Share on social media