A group of ancient Christian hemit caves known as Davit Gareja in Georgia and Keshikchidag in Azerbaijan straddles the border on a semi-desert scarp. Could the site’s management offer an opportunity for cultural cooperation?

Image: MehmetO/Shutterstock

Lonely Planet travel guidebooks have described the ancient monastery site of Davit Gareja as one of Georgia’s most remarkable historical sites, a collection of holy Christian establishments with a sense of “uniqueness heightened by a lunar, semi-desert landscape.” The main tourist attractions here are the reconsecrated monastic buildings of Lavra and the nearby hermit[1] caves of Udabno, climbing a steep scarp that rises to form a panoramic ridge overlooking Azerbaijan. Some cave ruins still partially preserve frescoes dating back to the 10th century. The sites themselves are even older, originally dating from the 6th century when ascetic monks from Syria arrived in the region to practice and spread a meditative form of early Christianity.

Udabno caves. Image: Mark Elliott

The Lavra-Udabno site is just one of at least 15 such complexes dotted about the surrounding area, including fortress-style towers once used to send messages between the monastic communities. These communities reached their peak activity between the 10th and 13th centuries, increasingly enjoying Georgian royal patronage. In 1154 King Demetre I of Georgia retired here to spend most of the last two years of his life in reflection and prayer.

This was the start of a ‘golden age’ for the monasteries. A distinctive school of painting is now associated with the complex – many of the portraits of Georgian royal personages are the only images of such historical figures to have survived. The monasteries were sacked in 1265 by Mongol forces during the Berke-Hulagu War and again in 1399 by Timur, but the communities were re-established each time.

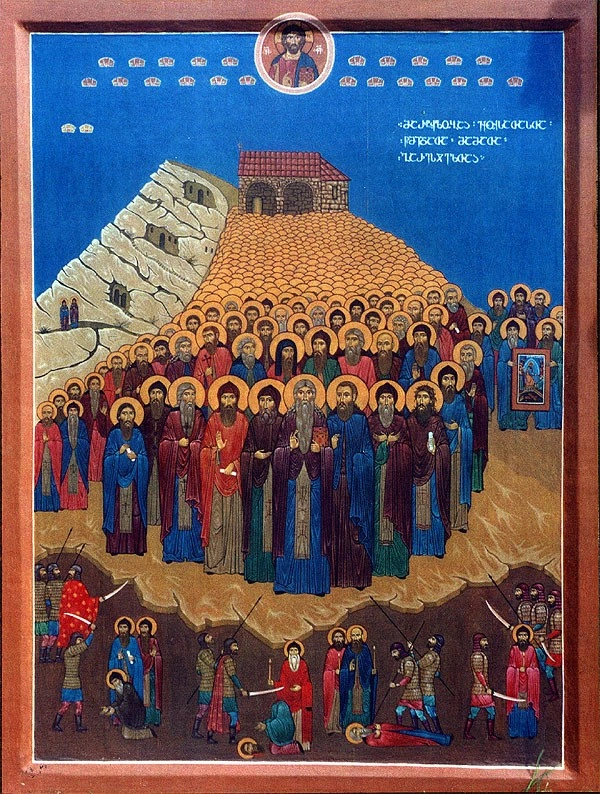

The 6000 martyrs of Davit-Gareja. Image: oca.org

Worse was to come in 1616 when some 6000 monks were massacred on Easter night by the armies of Safavid Shah Abbas I. The victims were collectively declared saints en masse by the Georgian church. Their bones were collected in the 1660s by King Archil and placed in a reliquary within the restored Transfiguration Church at Davit-Gareja. Some say that these relics still exude a spontaneous aroma of myrrh, a ‘miracle’ that helped draw more devotees as the monastery returned to life.

However, the community dwindled during the later 19th century, and eventually, the site was largely forgotten. Indeed much of the region was used for Soviet artillery practice from 1948 and particularly after 1979, when the area’s perceived similarity to Afghanistan made it seem like a good place to test military manoeuvres. Shelling was stopped in 1987 following demonstrations from increasingly vociferous Georgians, worried about the destruction of these cultural sites. Following Georgian independence, the Lavra Monastery and two other sites were reconsecrated, allowing a small number of monks to return.

Lavra. Image: Ilia Torlin/Shutterstock

Since 2007 the site has been on UNESCO’s tentative list for World Heritage status. The fact that Georgia had taken a unilateral lead in this process has added to a degree of friction with neighbouring Azerbaijan. After all, one of the most visible fortress towers, known in Georgian as Chichkhituri, along with some 70 caves of the upper Udabno ridge, lies right along the provisional borderline between the neighbouring states. And what little remains of the Bertubani monastery is entirely on the Azerbaijan side. Together these fall within a 25 square km reserve known in Azerbaijani as Keshikchidag, reached by a very rough unpaved track from the Aghstafa-Boyuk Kasik road.

Keshikchidag, from the Azerbaijan side. The fortress tower is known to Georgians as Chichkhituri. Image: Mark Elliott

The troublesome section of the border line is, as with so many frontiers between former Soviet states, only imperfectly delineated. The disagreement here is nowhere near as conflict-prone as between the Central Asian states over the Fergana Valley or between Armenia and Azerbaijan. However, it is nonetheless an annoying element of friction between otherwise cordial neighbours. Negotiations attempting to solve the issue started in the early 1990s, with Georgia hoping to establish control of the area, citing cultural claims. After all, Georgian monks had used the site for generations. However, Azerbaijani historians point out that the original founders were not Georgians and ascribe the site to Caucasian Albania, another Christian entity in this area of the Caucasus. More significantly, Azerbaijan understandably sees the prominent ridge-tops in the disputed zone as strategically significant, given their sweeping views across a vast swathe of Azerbaijani territory.

Udabno Ridge: many of the caves cut into the south-facing cliffs are former hermit dwellings, some with ancient murals. Image: Mark Elliott

Discussions about finding an amicable solution to the border issue have been spluttering on since 1991. In 2005 and 2006, several concerted attempts were made to settle the issue. However, a campaign by parts of the Georgian mass media calling for quick results backfired, creating a counter-reaction in the Azerbaijani press. Since then, a range of approaches has been suggested, including territorial swaps and a ‘neutral’ transnational space allowing easy access to pilgrims, monks and tourists. None have proved mutually acceptable, the latter idea being batted aside by the Patriarchate of Georgia as well as by politicians.

Azerbaijan’s 2019 launch of a “new border post” at Keshikchidag was announced in the Azerbaijani press as though a breakthrough had happened. However, as yet, the post has concerned itself mainly as a base for deterring illegal cross-border infiltration. Indeed, after its installation, visits to the Udabno ridge became far more difficult, as the access path to many of the popular cave sites pass through a stretch of Azerbaijani territory.

Image: Gareji Line/FB

The tightening of border controls led to a sizeable demonstration from Georgian Christians calling for leaders to do a better job at finding a solution with their “Azerbaijani brothers.” It has also made visits to Udabno unpredictable from the Georgian side, though tourists and pilgrims do still come regularly to visit Lavra,

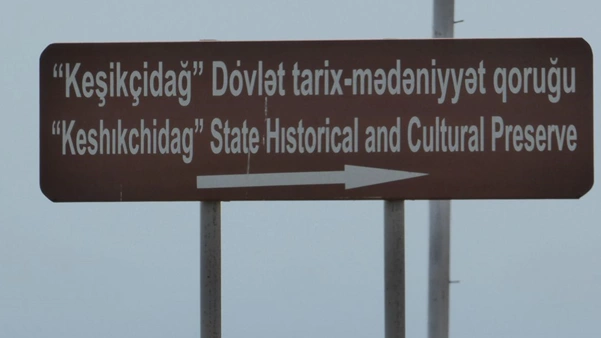

Signs imply that Keshikchidag is an established tourist site, but for now, approaching from the Azerbaijan side requires considerable red tape and should not be undertaken as a spontaneous whim. Image: Mark Elliott

Currently, visits from the Azerbaijani side are not practicable. Despite tourist-style white-on-brown road signs pointing towards Keshikchidag, the site itself is closed to visitors. Hopefully, a sensible bilateral solution will be reached, eventually making it easy to access this magical place from either country.

[1] Some sources suggest that the term anchorite might be more accurate than hermit as a descriptor for the lifestyles of the individuals who consecrated their lives to prayer in these caves.

Share on social media