- Home

- History of the Caucasus: At the Crossroads of Empires – Book Review

History of the Caucasus: At the Crossroads of Empires – Book Review

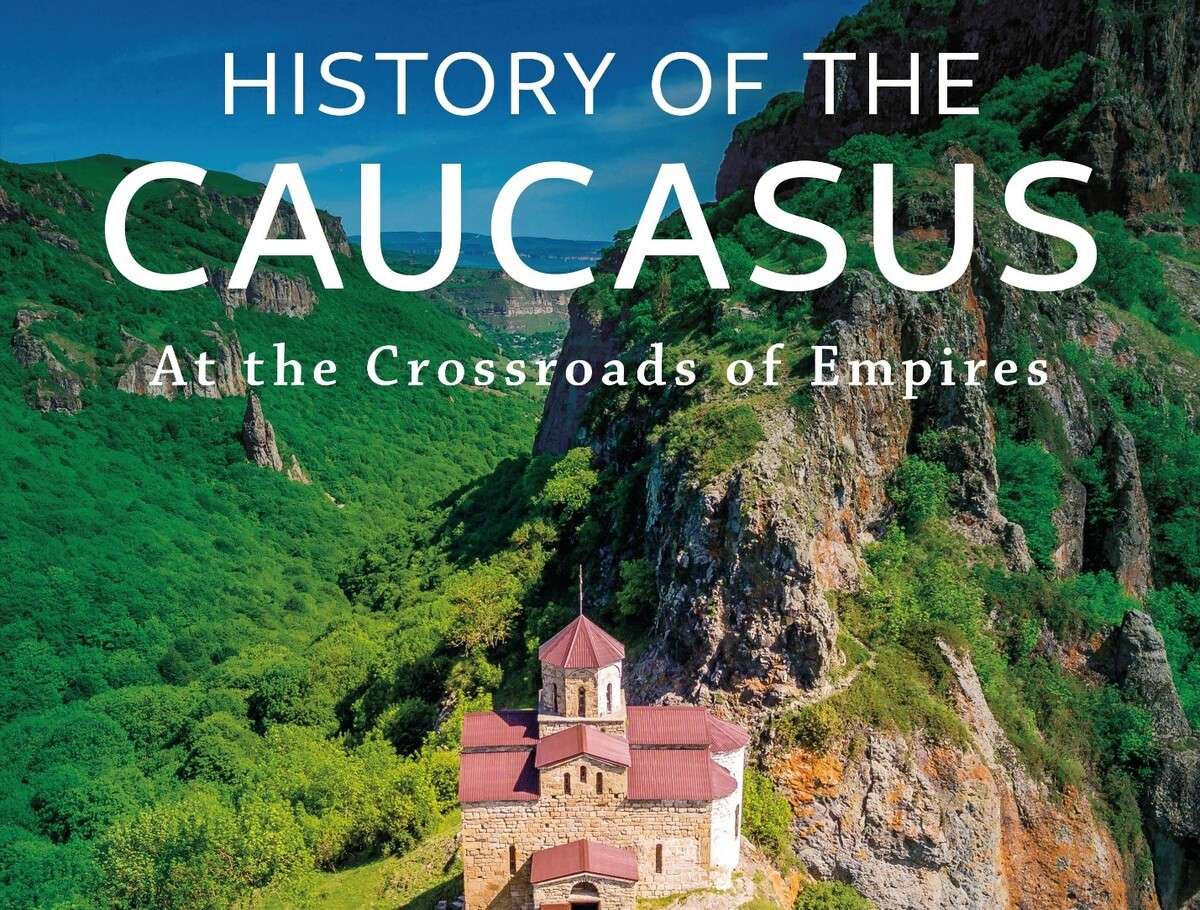

Christoph Baumer's latest book from I.B. Tauris publishers sets a new bar for scholarship when it comes to the Caucasus.

Christoph Baumer’s History of the Caucasus. The first volume takes the reader from pre-history to the Seljuk conquests of around 1050CE.

Christoph Baumer certainly doesn’t shy away from tough tasks. As if writing his four-volume history of Central Asia[1] wasn’t monumental enough, the explorer-historian has now published the first of two volumes covering the Caucasus. The Caspian Post couldn’t wait to take a look at Volume 1, subtitled “At the Crossroads of Empires,” and talk to Dr. Baumer about the project.

The book’s inner back page sleeve and map roughly show the area covered.

To call Baumer’s book ‘weighty’ is no understatement (in a very literal sense), as my postman will testify. Lavishly illustrated with the author’s colour photos taken on various visits to the region over the past decade, the heavy gloss paper gives the feel of a coffee table book. However, the content is that of a rich, old-school history text, fact-heavy and chronologically ordered with a suitably bewildering cast of kings and battles. Though the target audience seems to be mainly history students wanting something fully scientific in its reliability and referencing, the volume is made readable and contextualized for the masses by the many illustrations, photos and maps (laboriously tailored by the author).[SL1] In-depth fact boxes help add insight with particularly useful examples, including those on Caucasian scripts[2], pre-Christian Armenian deities[3] and medieval historians of the region[4]. In addition to a 21-page bibliography and two dozen pages of explanatory notes, the volume has an interesting triple index listed by person, place and concept. Population and language tables plus a large number of dynasty lists add further substantial reference potential.

Volume One weighs a hefty 2.4kg.

Geographically, coverage swings as far north as the Kelermes necropolis 10km north of Maikop, Adygea and the Greek cities of the Bosporan Kingdom, straddling the coasts of Crimea and the Azov Sea. Southwards we head as far as the Achaemenid inscriptions at Bisotun in Iran, where a 6th century BC Armenian is depicted as one of the nine ‘lying kings’ captured and crucified by Darius for apparently having falsely claimed to have been son of the last Neo-Babylonian emperor. Baumer also carries the narrative – and his camera - as far west as Nemrud Dağı (Anatolia) and southeast to Erbil (Kurdish Iraq) when the Caucasian links demand.

Baumer’s maps are full of fascinating detail: one example vividly shows the numerous historical “moods” of the Caspian Sea, whose vastly varying level has had enormous implications on the region’s pre-history.

In a Class of Its Own

Before Baumer, anyone looking for a scholarly yet readable English-language history of the whole Caucasus would have found the choice surprisingly limited. Thomas de Waal’s The Caucasus, An Introduction is an excellent primer for those wishing to understand the current conflicts in Georgia, Azerbaijan and Armenia. However, as a self-described ‘historian of the present,’ Tom’s work doesn’t pretend to delve deeply into ancient history, and his Caucasus book looks specifically at the South Caucasus countries. Most other available histories also concentrate on one geographical part of the Caucasus or one of the ethnolinguistic peoples of the region. A notable exception is James Forsythe’s 830-page[5] The Caucasus: A History, which does cover the greater region, including the North Caucasus. However, that book devotes barely 100 pages to look at the entire pre-medieval period that is the subject of Baumer’s entire first volume, and Forsythe’s brick-thick book also lacks colour plates. These features essentially put Baumer’s work in a class of its own.

When I asked him what he was most proud of in Volume 1, Christoph highlighted the sections that sketch out probable developments of ‘kurgan cultures’ in the Bronze Age. With no source documents available, piecing together diffuse elements of archaeological and genetic evidence made this an exciting prospect, and it’s a subject area that Baumer has investigated extensively in Central Asia too. It’s also rather daring in that academic research is developing rapidly in this field.

Baumer’s four-volume History of Central Asia came in a similarly lavish full-colour format.

In Chapter Four, the narrative hits its stride as we visit Colchis/Phasis (home of the legendary ‘Golden Fleece’) and Urartu, which, we learn, was known to its inhabitants as Biainili. The style is readable but aimed at university-level students, so if you aren’t familiar with terms like exonym[6], lithic[7] or betacism[8], consider keeping a dictionary handy.

One has to admire Baumer’s sheer persistence as he thrashes his way through so much material, weighing up the credibility of the relatively sparse ancient sources from eras where most ‘historians’ were neither primary researchers nor strictly interested in giving unbiased coverage of ‘facts.’ Yes – fake news was once far worse even than it is today. Even venturing a couple of adjectives about, say, a 2nd-century character, is taking something of a risk, much as it adds colour to the writing.[9]

An Explorer in the 21st Century

A Swiss citizen, Baumer is often described as an “explorer” and is the president of the Society for the Exploration of EurAsia, which he co-founded. He is credited with several extensive explorations in Southern Tibet and the Taklamakan Desert.

Christoph Baumer backed by photos from his explorations in the Central Asian deserts

“Doesn’t the term ‘explorer’ sound like something from another age?” I venture.

“Well, I’m approaching 70,” he jokes, “so maybe I’m from a disappearing generation.” He proceeds to outline his understanding of the related terms exploration and discovery.

“Exploration for me is quite broad – searching for unknown places, unknown monuments… but also it is searching for new contexts… and new connections between different events.” Discovery is “not only to be the first to find something but also to understand what one sees… I try to do both!”

Ayala Mazar necropolis, a remarkable Bronze Age site discovered by Baumer in 2009

Perhaps the most exciting of his discoveries in Central Asia was the remote Bronze Age cemetery of Ayala Mazar, reached laboriously by camel caravan across the deserts of Xinjiang, Western China, in 2009. The site’s great importance had previously been entirely overlooked, but Baumer’s findings revealed human remains dating back to at least 1660BC, including incredibly well-preserved Indo-European skulls, some retaining hair. Christoph also visited the site of two Bronze Age settlement sites. He found enough evidence to suggest common a unified cultural sphere of that era stretching over 600km to Xiaohe in the Lop Nor Desert.

Yeddi Kilsa – ruins of an Albanian monastic complex near Lekit, Azerbaijan. Image: Wikimedia Commons

In the Caucasus, he didn’t do anything that he specifically labels archaeological exploration. However, he still had many an adventure, including getting temporarily stranded in no-man’s-land between Azerbaijan and Dagestan. Amongst the fascinations that initially spurred him to turn his attention to the region were the architectural fragments of many truly ancient churches. Not just those of Georgia and Armenia, he stresses, but also those in what today is predominantly Muslim Azerbaijan, a place previously called [Caucasian] Albania. He was particularly taken by ruins at Lekit. That small village in rural Azerbaijan retains the striking remnants of a monastic complex known as Yeddi Kilsa just north of the village. However, what particularly fascinated Baumer was the faint ruin of a 7th-century circular church site hidden in a hazelnut grove at 41.47849N, 46.84990E. Having been there myself, I can’t disagree with the sense of exploration required to find it, but Baumer’s insights go further, helping us to speculate that the site was once part of a residence of a Western Albanian Prince[10].

Christoph Baumer (left) talking online to Caspian Post writer Mark Elliott at length about the challenges and pleasures of writing his book.

As David Chaffetz points out in his own review, the “weft of history in the Caucasus is complicated by the fact that, since earliest times, history has been used to advance political agendas.” The subject of Caucasian Albania is one such point of contention. It’s to Baumer’s credit that he takes a balanced, independent position on the subject, likely to annoy more vocal Azerbaijanis and Armenians alike.

While accessing records and historical sites in mutually antagonistic countries and breakaway states held obvious challenges, Baumer insists that he did not feel the need to censor his work other than for the sake of space. Perhaps the area he most regrets being unable to cover in greater depth was heretical Caucasian versions of mainstream religions. Some examples are the Tondrakians and the Khurramites – the latter being followers of Azerbaijani resistance hero Babak.

More to Come

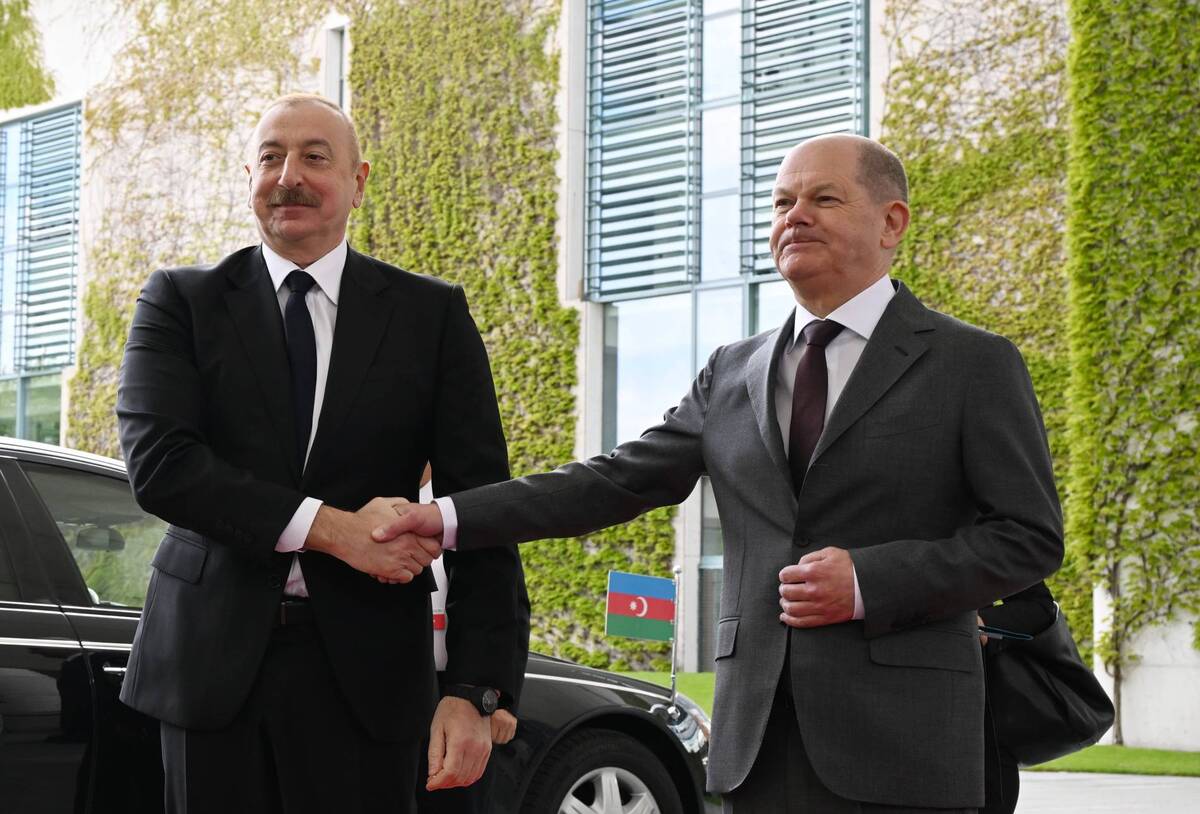

Before its abundant appendices, Volume One’s main text concludes with a five-page Outlook section that very concisely brings the reader speeding through the Middle Ages, the Russian era and the Soviet Union and up to the Second Karabakh War of 2020. However, to read about all this in far more detail, you’ll need to wait for Volume Two. Borders are still poorly demarcated and ceasefires shaky, so it seems that will be a hard book to finish. Does Christoph see positive signs for long-term peace? As a historian, he takes a long view and reminds me how important it is to remember that history is a function of geography. The wild, mountainous Caucasus has shaped its peoples to be intensely focused on defending themselves from outsiders, but this also means that each group tends to be highly self-reliant. That means that any hopes of longer term unity between the Caucasus’ main peoples seems far off. In that way the region’s like a mini-Afghanistan.

[1] published progressively between 2012 and 2018

[2] pp191-193

[3] p130-131

[4] p145-146

[5] Or 898 pages including index and notes in the paperback edition

[6] p76

[7] p21

[8] p76

[9] Eg. p166 Caesennius Paetus, the Roman governor of Cappadocia (including Armenia) was apparently an “incompetent and cowardly commander.”

[10] Baumer, p235