The Middle Corridor trade route has been of great geopolitical importance since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine—not just over land, but in the sky too. Kazakhstan hopes to capitalize on this potential for increased air traffic and become a new transport hub between East and West.

Image: Aureliy/Shutterstock

Much ink has already been spilled about the emergence and importance of the Middle Corridor trade route linking China and Europe via Central Asia, the South Caucasus, and the Black Sea. A critical overland trade route in a time when trade via the Northern Corridor through sanction-hit Russia is severely hindered, developing the Middle Corridor as a viable alternative to the Northern Corridor is a global undertaking with enormous geopolitical implications.

But the Middle Corridor is taking shape not only over land but in the air too. In the first week of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, air traffic over Kazakhstan tripled as Russia closed its airspace to European airlines in response to almost all European countries closing their airspace to Russian airlines. This has forced European airlines flying between Europe and the Far East to follow almost precisely the same route as the Middle Corridor, only this time at 35,000 feet.

Little demonstrates the headache that the closure of Russian airspace has caused European airlines more than the plight of the Finnish national carrier, Finnair. Before 24 February 2022, Finnair took advantage of Finland’s position on the most direct route between Western Europe and the Far East, offering indirect flights at more competitive prices than direct flights operated by their rivals.

The closure of Russian airspace to Finnair sent shares in the airline down over 20% and put this pillar of their business model under considerable strain. Routes were cut, and revenues were hit as the length of Helsinki-Asia flights increased by 10-40%, a situation further exacerbated by record-high jet fuel prices. Fast-forward to 2023, Finnair is surviving the closure of Russian airspace thanks to increased demand on routes to China and the U.S., but “significant uncertainty” persists in their operating environment.

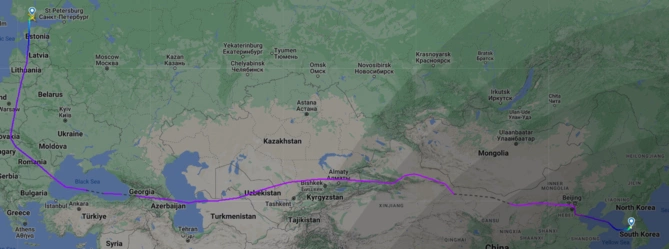

Map is of Finnair flight AY41 on 4 June 2023. Image: Flightradar24

Given this situation, Kazakhstan is especially well-placed to offer alternative and more competitive air connectivity between Europe and Asia. The above map shows Finnair flight AY41 from Helsinki to Seoul, which is now forced to make a considerable diversion around closed Russian airspace through Central Asia, as are many flights between Europe and Asia since the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine. Kazakhstan has a clear opportunity to capitalize on not just Finnair’s woe and many other European airlines like it, but also to claim Moscow’s former status as a critical Eurasian air hub.

Thus, Kazakhstan’s aviation industry is pushing to rapidly develop a sprawling route network with Europe, East Asia, and the Middle East to complement the increased interest in Central Asia coming from these regions, to better facilitate cooperation with them, and, with any luck, to permanently deprive Moscow of the Eurasian air hub status it once enjoyed.

In September 2022, it was reported that the EU and Kazakhstan were looking to increase the frequency and geography of flights between them. In January 2023, Kazakhstan and Japan entered into negotiations over resuming old routes and opening new ones. In April 2023, Kazakhstan and South Korea announced their intention to commence direct flights. Moreover, in May 2023, the UK and Kazakhstan agreed to considerably increase the frequency of civilian and cargo flights by the end of the year.

2023 will also see increased flights between Kazakhstan and Saudi Arabia as well as with the UAE, and in May, it was announced that Kazakhstan and the U.S. have also begun negotiations over commencing direct flights. Meanwhile, Air Astana’s CEO Peter Foster recently said that there are “big opportunities” in China, India is doing “very well,” and Pakistan is a “growth market.” In total, Kazakhstan aims to establish 25 new direct air connections by the end of 2025, including with New York, Paris, Vienna, and Singapore.

There is competition too. On 5 June, Georgian Prime Minister Irakli Garibashvili announced plans to build a “modern, new airport of international class” in Tbilisi so it can become an “actual aviation hub in the region.” Indeed, the same flights that are forced to fly over Kazakhstan between Europe and the Far East must also fly over Georgia. The race to join Istanbul as Eurasia’s next critical aviation hub after the demise of Moscow is very much on.

Another interesting part of Kazakhstan’s aviation sector is Air Astana’s stopover holiday program, where transit passengers can book a short stay in Astana or Almaty before continuing to their final destination. Launched in 2013 to boost tourism and resumed in late 2022 after the pandemic, it has taken on a renewed potential as Kazakhstan looks to cement its status as Eurasia’s next big aviation hub.

While the number of people who used this scheme between 2013 and 2019 was pretty small at just more than 59,000, as the number of connecting flights through Kazakhstan increases, it is almost certain that the number of stopover holidays will too. And, if the theory holds, this would entice people to stay in Kazakhstan a little longer next time, thus pushing the country - and potentially the wider region - up the global tourism ratings.

Russia will likely remain an international pariah for years or even decades to come, and its isolation is forcing global transport routes both over land and in the air southwards. Therefore, Astana and Almaty are perfectly positioned to open up another vector along a critical trade route which, this time, does not have to worry too much about enormous deserts, inland seas, and towering mountain ranges. To that end, Kazakhstan is very much sitting in the proverbial cockpit as the Middle Corridor takes flight, wasting no time in seizing what Moscow’s airports lost and changing the face of east-west air connectivity in their favour.

Share on social media