Molla Nasreddin magazine highlighted the hypocrisy of the Muslim clergy, the inequality of women, the imposed backwardness of the poor due to inadequate education and the unreasonable disdain of the Russified intelligentsia towards all things Azerbaijani.

Image: Wikimedia Commons

Very often, the statues you find in the Caspian region are of regally adorned poets, ardent politicians or valiant warriors – the latter often seated upon a galloping steed. However, from Uzbekistan to Turkiye, you’ll occasionally stumble across an altogether more comical figure - a clownish old fellow riding an undersized donkey that he seems in danger of crushing with his portly bulk.

In Bukhara, Samarkand, the man is waving distractedly while coming perilously close to losing his loose, pointed slipper. In several Turkish cities, you’ll find the same figure riding the donkey backwards.

That’s because this character is no typical warrior hero. He’s a philosopher-jester famed for an almost unwitting wisdom and speaking truth to power. He’s known as Nasrettin Hoca in Turkiye or Molla Nasreddin further east, both Hoca (Hodja) and Molla meaning ‘teacher’ or ‘spiritual guide.’ In parts of Central Asia, the name is Kozhanasyr. But the different names all refer to the same amiably straight-talking figure.

There are many claims that the character is based on an actual individual supposed to have been born in 1208, around 100km southwest of today’s Turkish capital, Ankara. Others say that such a man lived in Central Asia.

However, Molla Nasreddin has long since become an archetype – a humorously figurative character who might be the butt of a joke yet still manages to come up with wise nuggets. These are seen as having a range of meanings in cultural and political contexts and, at times, appear to have a satirical edge. Indeed, Molla Nasreddin has become so well known as a veritable genre of storytelling that his name has become associated with an anecdote-telling art form inscribed by UNESCO on the list of intangible cultural heritage of humanity since 2022.

The typical structure of a ‘wise’ Nasreddin aphorism goes something like this:

Molla Nasreddin was serving as qadi [Islamic judge]. A case was brought between two of his neighbours who had a dispute.

Molla Nasreddin listened attentively to the charges of the first and concluded carefully, "Yes, dear neighbour, you are quite right."

Then the other came to him. Nasreddin listened to his defence with similar concern and pronounced: "Yes, dear neighbour, you are quite right."

The Molla's wife, having overheard both conversations, scolded him: "Husband, both men can’t be right!"

Molla Nasreddin answered diplomatically - "Yes, dear wife, you’re quite right."

Meanwhile, a comically halfwitted Nasreddin is more in evidence with a tale like this:

One afternoon the Mollah realized that he’d dropped his ring in the living room. After searching for a while, he went outside and started looking in the yard instead. His wife found him there and quizzed him: "Husband! You lost the ring inside – so why are you searching for it in the yard?” Stroking his beard, the Molla answered: "The room is too dark, and my vision is poor. So I thought I’d look in the courtyard where there’s much more light."

Tales of this type are the foundation behind a long-running Molla Nasreddin periodical, a satirical Azerbaijani 8-page mini-magazine with cartoon-like illustrations in a style that has been described as “reminiscent of a Caucasian Toulouse-Lautrec” by talented artists, including Azim Azimzadeh and Khalil Bey Musayev.

It was founded in Tbilisi[1] by celebrated educator and writer Jalil Mammadguluzade (1866-1932), one of the many high-flying graduates of the Gori Seminary, a now-famous teaching college that imbued its graduates with an enlightened worldview. Publication started in 1906 during a brief era of expanding civil liberties and the temporary loosening of Russian imperial censorship in the wake of the 1905 Revolution. Conditions soon got tough again for most independent publishers, yet, incredibly, the publication continued until the Bolshevik revolution of 1917.[2] Mammadguluzade re-launched the magazine from Tabriz in 1921, moving it to Baku in 1922, where publication continued until 1931. The language was Azerbaijani, first in the Arabic script (until 1929) and later in the Latin alphabet.

Despite riding one of the most turbulent periods of Caucasian history, the Molla Nasreddin magazine remained relevant thanks to its bold sense of social conscience. It highlighted the hypocrisy of the Muslim clergy, the inequality of women, the imposed backwardness of the poor due to inadequate education and the unreasonable disdain of the Russified intelligentsia towards all things Azerbaijani. It also took on wider geopolitical issues, without Molla Nasreddin, the character, necessarily featuring in many an article.

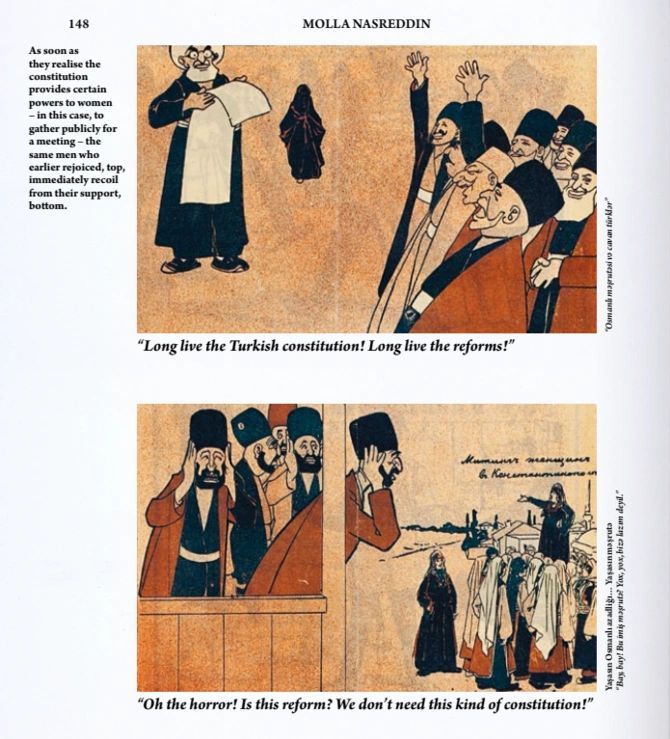

A fine example of the satirically ironic approach is a two-frame cartoon sketch. In the first, we see a group of cheering elders saying, “Long live the Turkish constitution! Long live the reforms!” Below, the second frame shows the same elders covering their ears and grimacing as a group of scarf-clad ladies listen to a female speaker. The caption reads, "Horror! We don't need this kind of constitution."

This and many others are shown pictorially with English language explanations/translations in the 2011 book Molla Nasreddin: the magazine that would’ve, could’ve, should’ve by Slavs & Tatars (available as pdf here). In Baku, many a museum displays an original issue or two of the magazine. And an 8-volume collection is occasionally available in bookshops for the most passionate Molla Nasreddin fans to reference the complete back catalogue in printed form.

[2] Albeit with frequent legal challenges from the authorities and temporary bans imposed in 1912 and 1914.

Share on social media