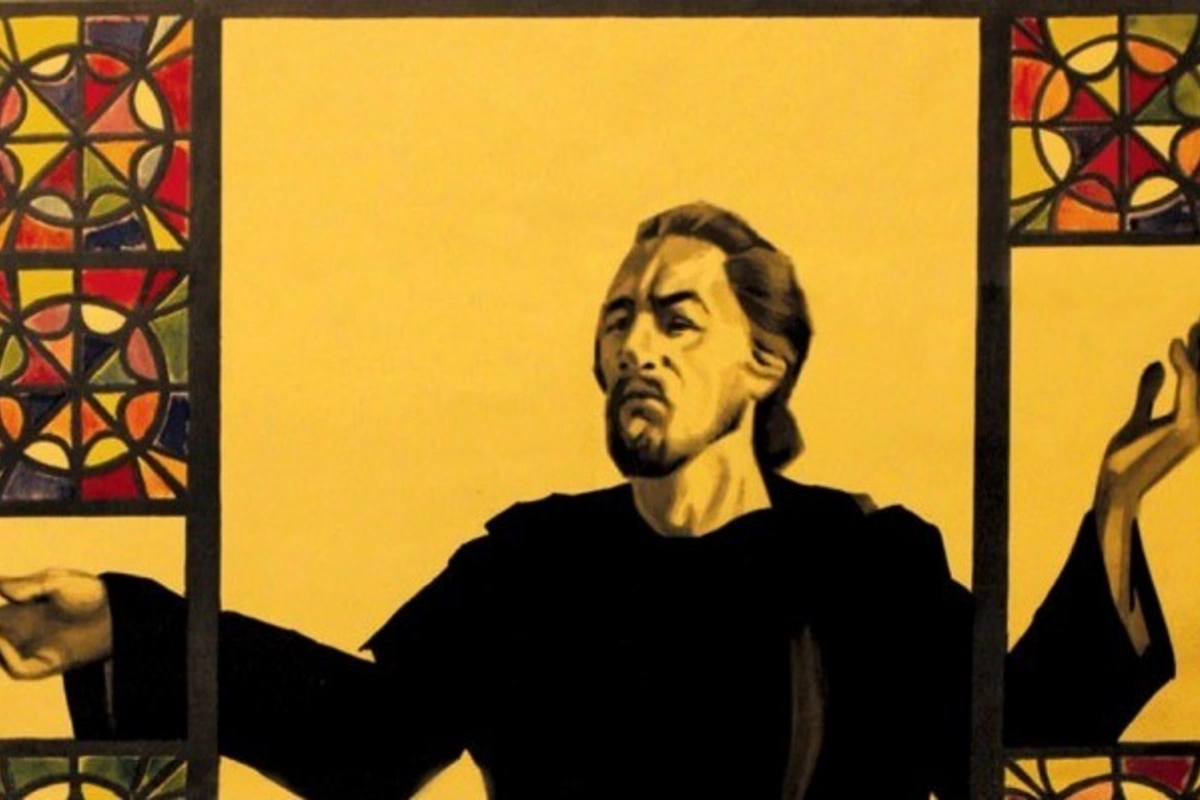

Sergei Paradjanov's The Colour of Pomegranates (1968) is a beautifully stylized examination of the 18th-century minstrel poet who went by the pen name 'Sayat Nova.' He composed songs in Azerbaijani, Armenian, Georgian and other languages.

Image: Wikipedia

For some critics, Sergei Parajanov’s 1968-9 movie,

For a first-time viewer with no knowledge of the Caucasus, it’s easy to imagine that the almost wordless film is just a plot-less work of art. However, there are whole

The poet in question is ‘Sayat Nova.’ That’s a nom de plume which means ‘King of Song’ or ‘Song Hunter,’ though he was originally christened Arutin (an alternative form of Harutyun, or Anastasius).[4] What makes Sayat Nova particularly important is not just the musical and philosophical qualities of his work but also the fact that he composed in all of the main languages of the Caucasus - Armenian[5], Georgian and Azerbaijani-Turkish[6] with occasional snippets of Russian and Persian. Like his work, his background reflects the ethnic melting pot of the region. He was born sometime between 1710 and 1724, with 1722 or 1712 the most popularly believed dates. His father, Karapet, possibly had Syrian or Turkish roots, while his mother was Armenian from the Avlabari district of Tbilisi, Georgia. Arutin considered himself Armenian by religion, even if he possibly saw Georgian as his mother tongue.[7] He was probably educated at Sanahin, but spent important years as an itinerant ashug (troubadour-style wandering musician), settling eventually at Telavi, then Tbilisi, where he was a performer and diplomat of Georgia’s King Erekle II. According to legend, he had to flee the court in 1759, having fallen in love with the king’s sister, Anna. However, it’s equally likely that he was, in fact, banished for pushing his satirical jokes a little too far. He then changed his name to Stepanos and took religious vows as a kahanay (a wedded priest: he was married with four children).

Or so it’s believed. The primary source of most biographical details comes filtered through the poetic prism of Sayat Nova’s own songs, so it can be hard to be sure what is fact and what is allegory. Perhaps it is not so surprising that for The Colour of Pomegranates, Parajanov decided to avoid a standard biographical approach altogether and instead symbolically attempted to “

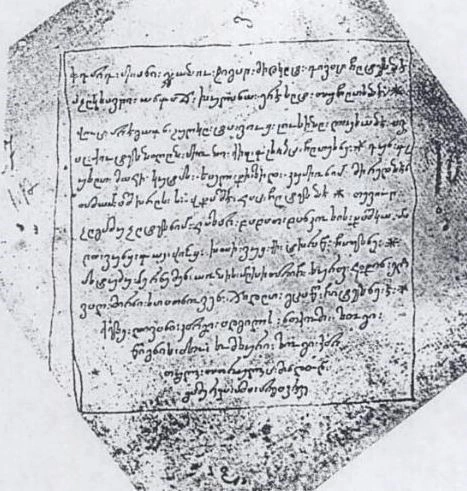

Sayat Nova’s work is better preserved than his life story... unusually so for an ashug, whose creations are essentially oral by tradition. In part, that’s because Teimuraz, the grandson of his former patron, ‘collected’ them a generation later. But also, it’s because Sayat Nova’s own ‘Davtar’ (notebook) still exists, containing numerous songs written in his own hand. Curiously he used Georgian script for most of the Armenian works, yet Armenian script for many of the Azerbaijani ones.[8] Ever playful, he also “forged his own literary languages, mixing Western and Eastern forms in Armenian, larding his Georgian poems with Turkish and Persian words.”[9] His ‘Poem in Four Languages’ is just that, using Azerbaijani, Armenian, Georgian and Persian. On at least one occasion, he even mixes Georgian and Armenian scripts within single words, creating a kind of lexical game.

Dard mi ani ‘Do not cause (me) pain’ was written at 45 degrees to the page in Sayat-Nova’s own hand, using alternating Armenian and Georgian script.

Sayat Nova’s death in 1795 coincides with the sacking of the whole Caucasus region by the Qajar forces of Iran’s ‘eunuch shah,’ Agha Mohammad Khan. The fact the poet died violently at Haghpat Monastery has led many to suppose that he was one of the Christians who chose execution rather than forced conversion to Islam. But through his work and legacy, what comes through is not a message of cultural division but one of seeing the poetic beauty of shared humanity. That was a feature that encouraged Sayat Nova’s renewed popularity in the Soviet Union’s Khrushchev years and later.

Despite his profound faith in the Armenian Apostolic Church, his words could also be phrased in terms that meshed with Muslim Turkic audiences. There was also a fair admixture of Persian Sufi thinking in his philosophy, in which references to the divine are rarely explicit. Thus his work is generally spiritual rather than religious and often impressionistically romantic. This, along with his humble beginnings, made his ‘resurrection’ easier for Soviet arts scholars who could strip his biography of its religious aspects to fit with the USSR’s atheist mores.

These days Sayat Nova’s songs remain very well known among Armenians. Dun en Glkhen (You were a wise man) is available in an exceptionally vast array of versions, each pregnant with a powerful kind of melodic anticipation. A fine example, very professionally recorded, is that of Razmik Baghdasaryan accompanied by Arsen Petrosyan on duduk. But the song shows up all over the place.

Another Sayat Nova classic song to have retained enormous popularity is Tamam Ashkharh (“The Whole World”). A

While it’s great that Sayat Nova has continued to be widely celebrated in Armenia, at times, the poet is dubiously misappropriated as a

When Azerbaijanis use tunes associated with Sayat Nova, there can be controversy. For example, Azerin’s 2003 song

It’s time that nationalism was put aside when thinking about artists and historical figures who came well before those nation-states. Especially figures as elusive yet as multi-cultural as Sayat Nova. This was something that Sergei Parajanov clearly saw in making

[1]

[2] Sections of

[3]

[4] Many references give his full name as Harutyan Sayadyan, but according to a seminal work on Sayat Nova’s life and work by Charles Dowsett, it’s likely that the poet didn’t actually use a surname and that this has been retrospectively added by common practice.

[5] In both Tbilisi and more standard dialects

[6] More specifically the Borchali/ Ayrım dialect

[7] Dowsett, p7 suggests that with his mother, at least, all correspondence was in Georgian.

[8] Such ‘Armeno-Azerbaijani’ was the common convention among Armenian ashugs for their Turkic songs

[9] Dowsett, p8

Share on social media