Read our review of the brilliant, brick-thick novel 'The Eighth Life.' Nino Haratischvili tells the gripping if harrowing story of 20th-century Georgia through an intensely personal series of fictional life stories.

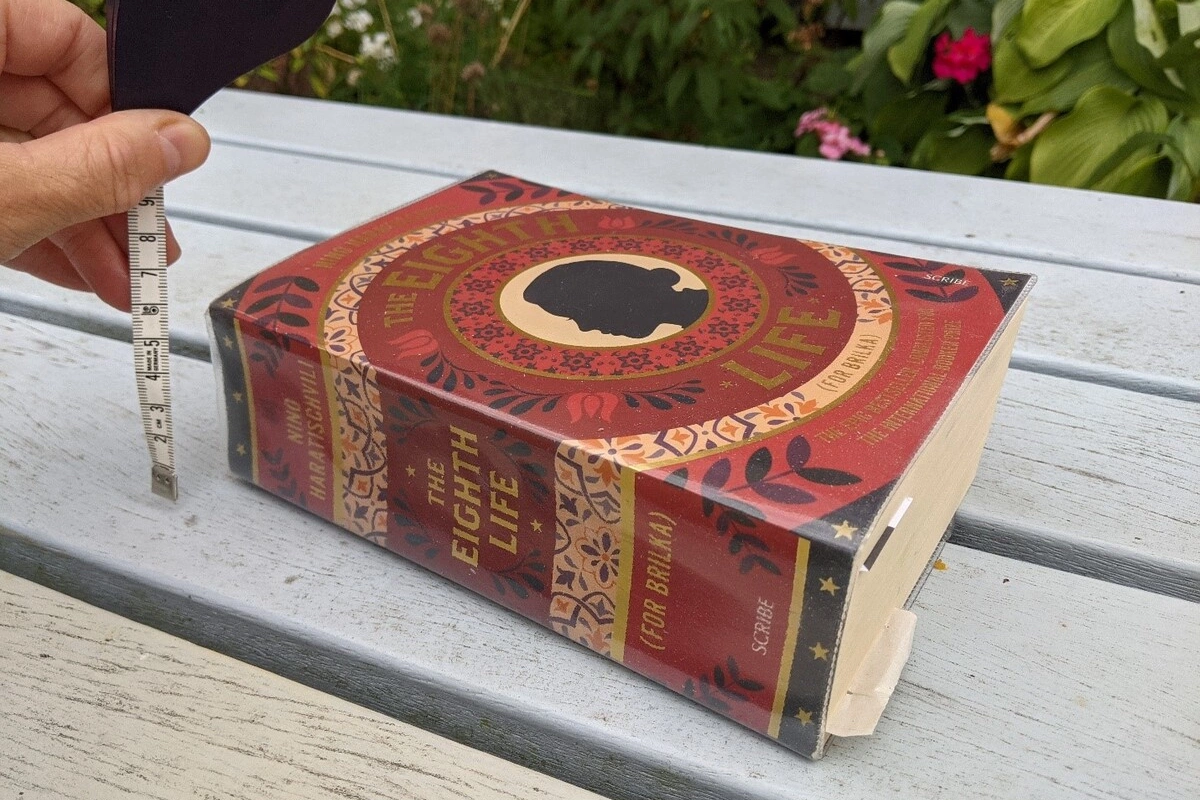

Even in its small-print English language edition, The Eighth Life is 6cm thick. Image: Mark Elliott/The Caspian Post

The Eighth Life is a truly epic novel. Germany-based Georgian author Nino Haratischvili tells the intricate life stories of seven members of a Georgian family that’s fictional but historically grounded. Each is as full of passion, tragedy, dashed hopes and surreal coincidences as that of the nation itself.

“A carpet is a story. And hidden within it are countless other stories,” the book’s narrator is told at the start[1] of the opus, and thereupon starts weaving – or unweaving perhaps – the complexities of not just her family secrets but also the tumultuous threads of Georgia’s 20th-century history. The book’s sheer physical size is daunting in itself - the brick-thick paperback English translation runs to 935 pages of microscopic print. However, if you don’t have time to read it all, pages 8 and 9 alone somehow manage to encapsulate the complexities of “Georgian-ness” for anyone who might have been prone to mistaking Tbilisi for Atlanta.

The web of stories focuses overwhelmingly on relationships, compromised by oppression, buoyed by circumstance, broken by sexual brutality and trapped in a web of well-intentioned motives turned sour. While events are often harrowing, hope continually rises anew. The author’s way of placing members of the Jashi family into an unlikely plethora of pivotal moments in Soviet history serves a very important purpose. Most obviously, it allows readers who might be less familiar with the tribulations of the USSR to learn about pivotal events which appear as the backdrop to the Jashi’s personal missions rather than like a school history textbook.

Certainly, the action is all the more gripping for that, but one has to wonder about a few things… Could Stasia really have lived for months in an opulent Petrograd mansion, selling her friend Thelka’s knickknacks to survive as the October Revolution raged and Lenin consolidated power in 1917-18? Could Christine really have raced Hitler to Moscow in WWII? Could Kostya have survived both Stalingrad and a nuclear submarine accident? Could Kitty really have become a dissident singer, performing on a tank during the Prague Spring while her brother rose to run the communist party in Tbilisi? Could Niza really have escaped the April 9th, 1989 massacre through a school window?

One or two such tales might be feasible. Threading them all together as the exploits of the one family stretches the bounds of credibility. But that’s far from a criticism – indeed, pushing the characters into such key historical junctures helps by making them feel semi-allegorical. The result is both intriguing and instructive while helping to soften what could have been unremittingly volleys of painful personal suffering. The book hints at how much worse things could have been by depicting in less detail the pitiful misfortunes of the ever-unlucky Eristavis. This character lacks the combination of talent and luck that helps soften the era’s horrors for the improbably gifted Jashis.

Emotionally, a common thread throughout the book is a deep sense of overwhelming disappointment due to life’s realities. For example, by the time she returns from Moscow, Elene had realized that “love was replaceable, that intimacy was a silken thread that could break at any time that feelings changed from day to day, and affection could breed contempt.”[2]

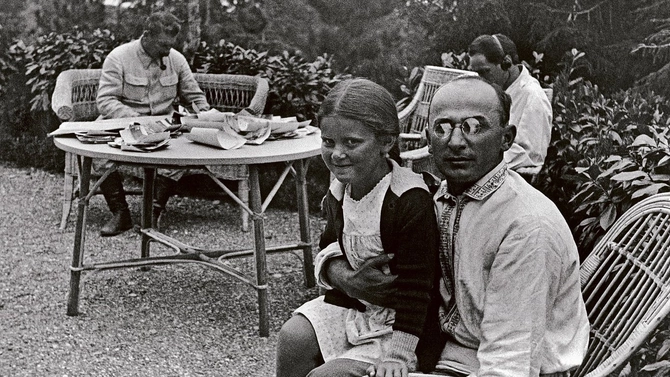

A particularly affecting sub-plot is the bitter-sweet gift of beauty bestowed upon Christine. She is forced – with heart-wrenching consequences – into an affair with the insatiable ‘Little Big Man.’ This Machiavellian snake of a character is a Champagne-drinking, opera-loving, Bugatti-driving bon-vivant, yet he is also the Caucasus’ top Communist. Like the Generalissimus (Stalin), he is never actually named in the book, but undoubtedly he represents pre-KGB Soviet bogeyman Lavrentiy Beria, right down to the wire-framed pince-nez glasses.

There is no doubt of the author’s love for her homeland, but it is tinged with a degree of frustration. Notably, there’s an ambivalence in explaining Georgia’s numerous historical interactions with Russia, highlighted with richly nuanced delicacy.

Musing on the Brezhnev era, the narrator marvels “what a comfortable life the Georgian elite, including the intelligentsia, had established for themselves in their little piece of paradise during the decades of Bolshevik rule. How they had perfected the art of delusion, how good things were for them in their Russian trauma.”

People “didn't believe in a system or any ideology apart from perhaps the ideology of their own hedonism. People had realised that the position their northern neighbour had assigned to them really wasn't all that bad… One could be cultured, creative, musical, fond of drink, a little anarchic, yes, that too, but only a little; beautiful and talkative, lazy and hot tempered. What was wrong with that? After all, these are the characteristics we Georgians are proud to sight as part of our national identity.”[3]

And, initially at least, Kostya appears to be proved right that Georgia needs its Russian ‘big brother’ to prevent bloodshed and chaos after the suppression of the April 9th protests.[4]

Meanwhile, though the epic is very much a tale of women and their plights, a central pillar to the tale is the rise to power of school-friends Konstantin ‘Kostya’ Jashi and Georgi ‘the voice’ Alania. Both are receptive to the optimistic pioneer spirit of the inter-war USSR and become model communists. But, as their idealism fails, Kostya goes from bright-eyed hero via family fixer to ruthless moustachioed powerbroker, while Georgi makes a Faustian bargain to work as a guardian angel for Kitty while selling his soul as an agent of the KGB in London.

Through these characters, as well as a vast and assorted cast of artists, dissidents, black marketeers and mothers, Haratischvili has really woven together a Georgian literary carpet of such colour and complexity that you won’t regret unfurling all its 935 pages.

[1] p15

[2] p413

[3] p502

[4] p777

Share on social media