For an unusual side glimpse at the short-lived Azerbaijan Democratic Republic (1918-1920), take a look at the state’s small and appealingly basic series of postage stamps.

Image: spatuletail/Shutterstock

For philatelists, collecting the stamps of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic (1918-1920) is a fascinating yet relatively inexpensive and straightforward task. The newly independent republic had continued to use Russian stamps well into 1919, something of a sore point for the new government as the system became prey to smugglers bringing in supplies from across the northern border. The issue was prioritized by a new minister of Post & Communications, a former lawyer called Jamobey Hajinski, who took over the position in April. Nonetheless, it wasn’t until October 10th that the ADR’s first designs were finally issued: ten denominations in four designs.

Image: Wikimedia Commons

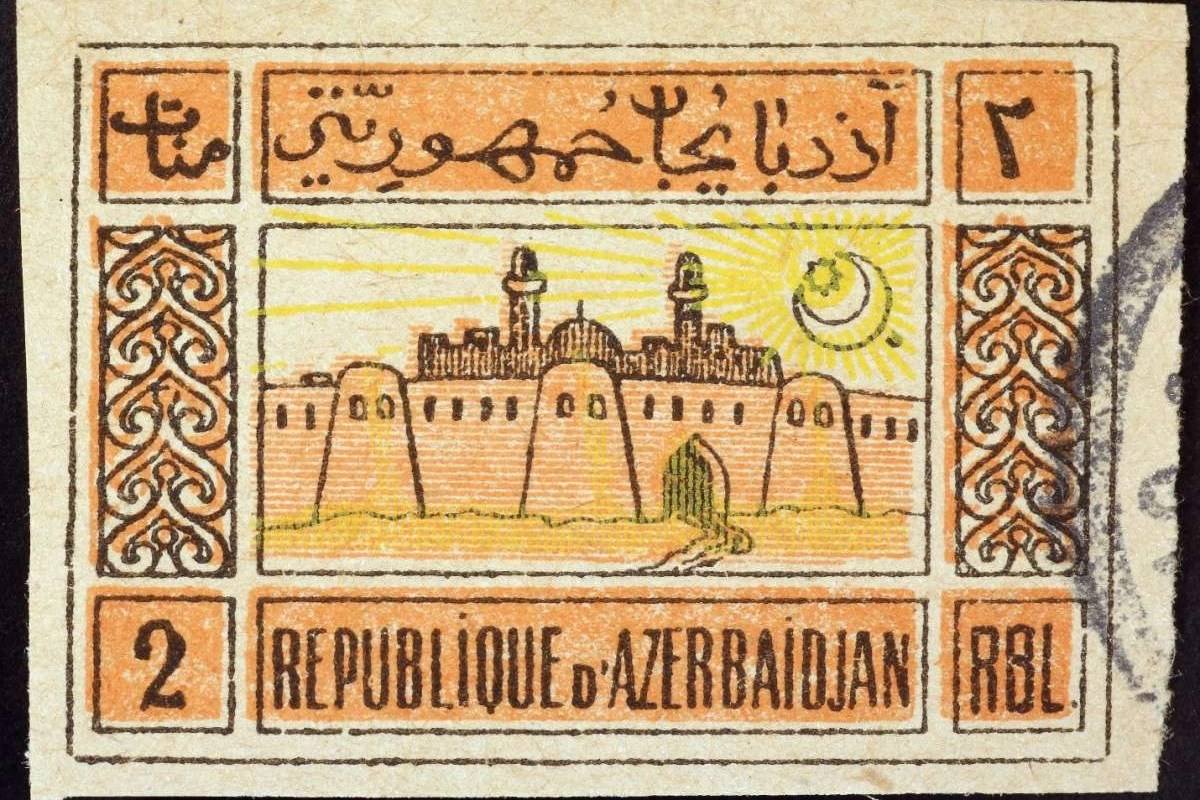

These included a soldier brandishing the national flag (10 kopeks, 20 kopeks) and a scythe-bearing peasant harvesting corn at sunrise (“Land and Freedom,” 40k, 60k and 1 rouble). Higher value stamps sported very stylized views of the walled old city of Baku (2, 5 and 10 roubles) and of the Ateshgah (fire temple) at Surakhany (25 and 50 roubles).

The quirky simplicity of the designs adds to the charm of the stamps, which are labelled “Republique d’Azerbaidjan” in French (the language of the Universal Postal Union) as well as in a cursive Arabic-Turkic script. The original paintings were by Zeynal bey Aliyev, a 24-year-old artist who had studied at Baku’s classic Realni College (“Special School”), later the setting for the classroom scene that opens the novel Ali and Nino, and now used as Baku’s Economic University.

Image: Wikimedia Commons

The stamps were printed using a fairly rough form of lithography which meant that some of the colours tended to be a little offset adding further to the low-tech appeal of the designs. In the hurry to get the stamps issued, they were produced without perforations – so sheets had to be cut with scissors. Compulsive collectors might feel the need to procure variants printed on different papers and with different gum.

By 1920, high inflation meant that even the 50 rouble Atashgah designs were insufficient to cover delivery costs, so a whole new set of stamps was commissioned. By this stage, Zeynal bey Aliyev had moved to Italy to further his studies at an art academy in Rome. So the new designs look very different – still primitive and this time mono-coloured but engraved rather than lithographed and with a more intricately realist style by a now forgotten artist. The standouts are the 25,000 rouble oil-landscape stamp and the 1000 rouble bridge scene, which probably depicts the 17th-century river crossing at Qazanchi in Nakhchivan.

The 17th-century Qazanchi Bridge in Nakhchivan as it looked before its whole-scale restoration in 2018. Image: azertag.az

The six designs were printed in both perforated and imperforated forms. For philatelic purists, these don’t qualify as postage stamps because, before they could be distributed, in April 1920, the Red Army had marched into Baku and the ADR’s independence was crushed. That means that, despite their historic relevance, this issue is extremely reasonably priced, often selling at under US$10 for the whole set.

The 1920 stamps that were never distributed to post offices. Image: Mark Elliott

After that, the next set of useable Azerbaijani stamps would be a 15-denomination 1921 issue inscribed in Russian and Turkic-Arabic as the Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic. An independent Azerbaijan wouldn’t issue stamps again until March 1992.

Image: Mark Elliott

Share on social media