- Home

- “The Truth Always Comes Out”—The Story of Rushan Abbas, Founder of the Campaign for Uyghurs

“The Truth Always Comes Out”—The Story of Rushan Abbas, Founder of the Campaign for Uyghurs

We live in a time when ethnic conflicts and identity politics are on the front pages of every news media. Yet one nation’s struggle remains unrepresented—the discrimination of Uyghur people in China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. We spoke with one of the most prolific Uyghur activists in the West, Rushan Abbas, whose personal story is intertwined with the oppression and genocide of Uyghurs in China from the very beginning.

Image: courtesy photo

In a world of politics, the struggle of a small Muslim nation living in China is often overlooked. It has been proven that since 2017, Chinese authorities have been imprisoning Muslims in East Turkistan, including Uyghur, Kazakh, and Kyrgyz minorities. The number of Uyghurs is overwhelmingly high. It was reported that at least one million Uyghurs had been put into Chinese camps, making the Uyghur region in China have the highest imprisonment rate in the world. Despite the leaked documents revealing this and Uyghurs worldwide speaking up about their experience in the camps, Chinese authorities deny it, claiming that those are re-education camps aimed to “counter terrorism and alleviate poverty” in the Xinjiang region.

“All my life, from the time I was born, I knew that Uyghurs are oppressed and being treated badly by the Chinese regime,” says Uyghur-American activist Rushan Abbas, who spent the majority of her life fighting for the rights of Uyghur people. One of her earliest memories is how the Chinese authorities came to take her mother to a re-education camp after her father had already been taken there. “When I was very young, maybe a year old, my mom was feeding me in her arms. She tried to hand me over to my grandma, but the armed guards didn’t even give her a chance to hand me to my grandma properly. They grabbed me from her arms and threw me over to my grandma. I was screaming and crying so hard,” Abbas remembers this horrific story. “My mom used to tell me, ‘For hours and hours, so far away, they were questioning me, shouting and yelling, I couldn’t hear anything because all I could hear in my mind was your crying voice.’”

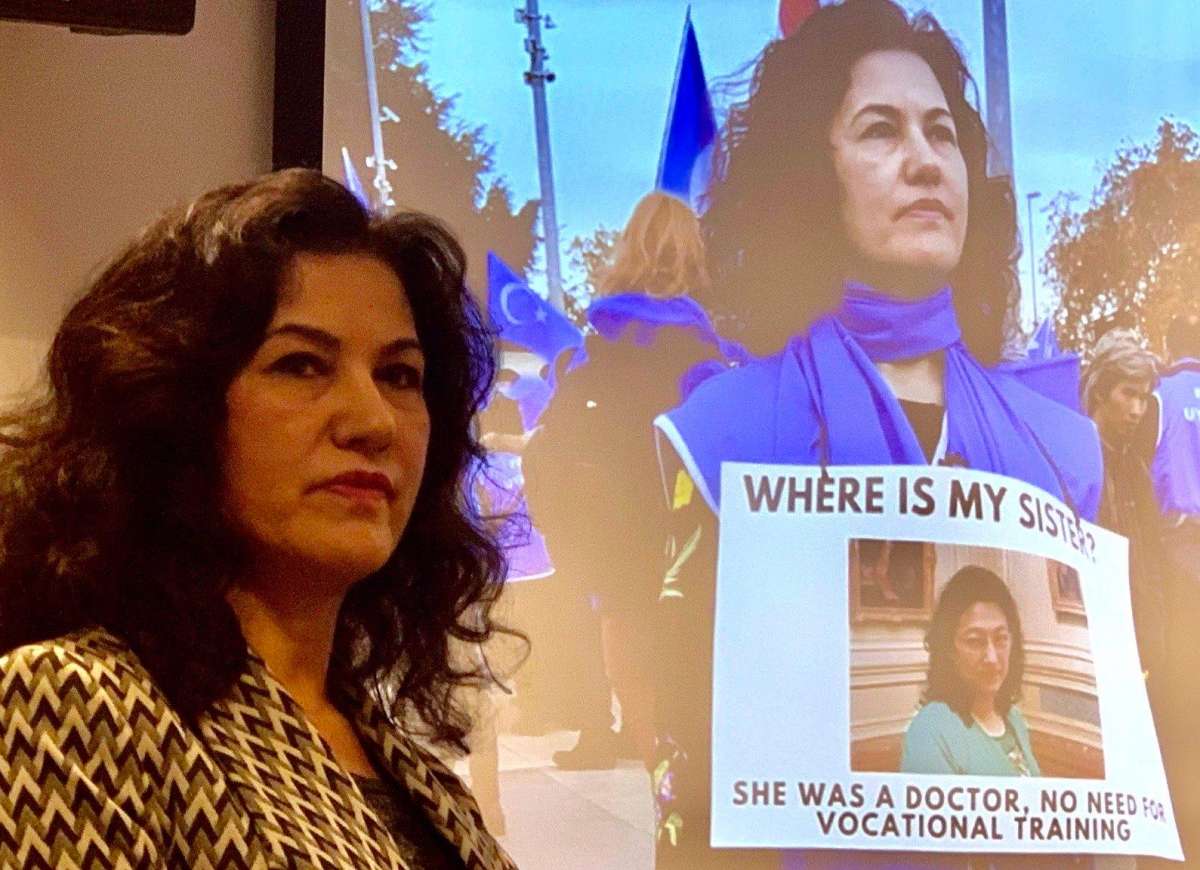

This early memory of terror is not the only one for the activist. For the past five years, she has advocated for her sister Dr. Gulshan Abbas’s release. The activist is certain that her sister was abducted as a result of Abbas speaking out on the genocide of Uyghur people in Xinjiang and the sudden disappearance of 24 members of her husband’s family. In order to bring awareness to this issue, they organized a “One Voice One Step Movement” in 14 countries on the same day. On 5 September 2018, Abbas was invited to speak in Washington, DC. “I spoke about genocidal policies and camps, massive detainment of Uyghur, Kazakh, and other ethnic groups in East Turkistan, and outlining the fate of my in-laws,” Abbas says. “The day that changed my life forever. Six days after that speech, which was televised on YouTube, my own sister Gulshan Abbas was taken.” A year after her sister’s disappearance, Abbas decided to quit her job and become a full-time activist.

Rushan Abbas and her sister Dr. Gulshan Abbas (right). Image: courtesy photo

Until 2020, the Chinese government accused her of lying and using other people’s photos, pretending to be her sister. In December 2020, as the activist explains, their family found through a reliable source that her sister Dr. Gulshan Abbas was imprisoned for 20 years. Gulshan, a retired doctor, whom her sister describes as “a law-abiding citizen” and “an ordinary grandmother and mother,” was detained for “taking part in organized terrorism, aiding terrorist activities, and seriously disrupting social order,” Amnesty International reports. That is the last piece of information known to Abbas and her family on her sister’s fate. “We have no official documents saying she is being held in a certain place, no information on her health, and no proof of life. We have no picture, no video, nothing since her detention,” the activist explains. “The Chinese government is not only getting away with genocide and crimes against humanity and such unlawful actions against innocent people like my sister, but they are massively producing propaganda videos and tools to deny their crimes by inviting journalists on tours, buying out influencers on social media, and spreading lies. If there is nothing to hide, why are they trying so hard to spread false propaganda?”

“I do feel guilty when I think about the years that my sister is still in a dark dungeon somewhere. When the weather gets cold, I worry if she has enough warm clothes. I wake up in the middle of the night and wonder what kind of place she is lying in or if she is able to sleep comfortably. But that guilt continuously fills me with the strength to fight hard,” Abbas explains. “The Chinese government made a huge mistake by taking my sister; they thought that maybe [it] would stop me from being vocal, but they just created a full-time activist because of it.”

Unfortunately, this wasn’t the first case of “retaliation” against Abbas’ activism. On 12 December 1985, she was one of 20,000 Uyghur people demanding better treatment and equal rights in China. Three years later, in 1988, Abbas took part in another demonstration, for which she soon suffered the consequences. In 1989, when she graduated from her university with a high academic score, she was not able to get a job in Xinjiang. “At the time, there were no private companies,” the activist explains. “My university sent me to an agricultural university to work as a teacher, but the agricultural university was pressured by the Xinjiang political bureau to decline my position.” Due to being unable to work, she decided to flee to the US and continue her studies.

Once there, Abbas never stopped advocating for the Uyghur people. In 1990, she was raising awareness for the Baren Massacre of Uyghurs that was happening at the time in China, which led to her father, Abbas Borhan, a scholar, academic writer, and chairman of the Science and Technology Council of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, being forced to retire at the age of 59. However, that wasn’t the end of the Chinese government’s actions towards her father. In 2005, the activist went to China for the last time for her mother’s one-year death anniversary. Since then, she has feared returning due to the increasing number of foreign citizens publicly protesting against the Chinese government’s mistreatment of Uyghurs being detained when visiting relatives in Xinjiang. Instead, Abbas tried to bring her father to the US. However, in 2006, the Chinese government annulled his passport in response to his daughter’s activism. For the last four years of his life, having passed away in 2010, Borhan wasn’t able to travel to the US to visit his daughter.

Image: courtesy photo

Abbas explains that ever since 1949, the oppression of Uyghurs in East Turkistan had different waves and justifications. “In the ‘50s [they] prosecuted Uyghurs under the name of nationalism. In the ‘60s, during the Cultural Revolution, they were persecuted; my grandfather was in jail for 3 years in the late 1960s.” However, things got a bit better when, in 1979, China established democratic relations with the US and joined the UN. The activist explains that for a brief period from 1979 to 1989, Uyghurs had a bit of freedom, hence the protests in the ‘80s that they were able to organize. Everything changed with the collapse of the USSR and the declaration of independence of the Central Asian states. According to Abbas, Uyghurs were then labelled as “separatists.” After 9/11, their label was changed to “terrorists.” “The Chinese government is always looking at international politics to justify their persecution of the Uyghurs,” she says.

As part of her fight for her sister’s release, Abbas produced a film, In Seach of My Sister. “The movie follows me and my husband’s advocacy, the story of my sister, and her detention,” she explains, adding that it features interviews with Uyghur activists, camp victims, Western scholars, and even “the Chinese government’s propagandists and genocide deniers.” According to Abbas, in response to the movie’s release, there was a special press conference in Beijing last year trying to disprove the verity of this documentary. “I take it all as an impact of my work.” Another example is the recent Jana Chekara film festival in Almaty, which was moved online due to pressure from the Kazakh government, which is known to be supportive of China’s Communist Party. In Search of My Sister was one of the movies that were going to be shown there. “One thing that the Chinese government is most afraid of is the truth. That’s why the Chinese government pressured the venue to cancel the festival because they don’t want the people to find out the truth.”

As for Abbas and her own safety, she is clear that neither fake news being spread about her by the Chinese government nor “indirect attacks online” will not stop her from being the voice of the Uyghurs in China. “I worry for my own safety, but at the same time, we all die once. If we all think about our own lives and safety, then who is going to do the work?” she says. “We have a proverb in Uyghur, ‘You cannot block the sun with a fabric.’ The truth is the sun, you cannot block it with anything. No matter what kind of propaganda and disinformation the Chinese government tries to spread, the truth always comes out.”