Photo credit: Pexels

By bypassing the South Caucasus and Central Asia, India’s new route to Europe rewrites not only trade maps, but geopolitical alliances. The return of Donald Trump to the White House in 2024 has already begun reshaping the post-Cold War global order. His presidency marks a dramatic pivot-especially in the Middle East, where tectonic shifts are underway.

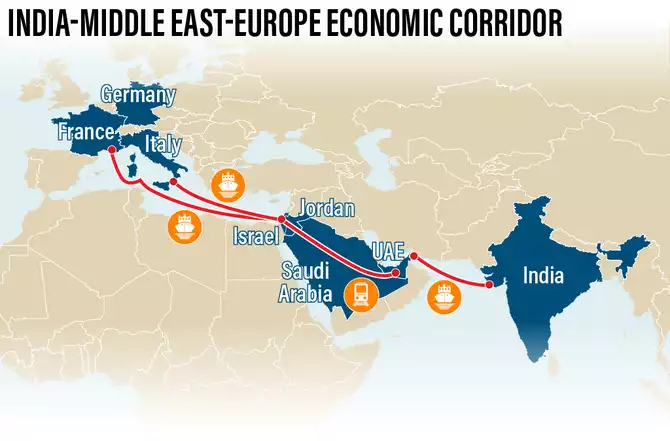

At the center of this transformation is the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC), a bold new trade route envisioned to link India to Europe via the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Israel, and Italy. It’s a project that Trump has already described as “one of the greatest trade routes in history”-and with reason. Unlike China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), IMEC isn’t just about logistics. It’s about realigning the world.

Photo credit: thenationalnews.com

The corridor is more than an economic shortcut. It’s a geopolitical maneuver-an attempt to redraw alliances, dilute Chinese influence, and isolate traditional regional chokepoints like Pakistan and Iran. The route entirely bypasses the South Caucasus and Central Asia, regions once seen as inevitable connectors between East and West. That decision is as symbolic as it is strategic.

Iran, for one, is watching these developments with growing concern. Its attempt to block Israeli-Saudi normalization through the Hamas-led October 7 attacks has backfired spectacularly. Tehran now finds itself increasingly isolated, its proxies in Lebanon, Syria, Yemen-and Gaza-under siege. Meanwhile, Saudi Arabia and Israel inch closer to formal ties, bolstered by shared interests and a joint future built around trade and technology.

At the heart of this vision lies a vast logistics infrastructure: ports, railways, digital cables, and even a clean hydrogen pipeline. Indian cargo will travel by sea to the Emirati port of Fujairah, then move overland by rail across Saudi Arabia and Jordan to Haifa, Israel. From there, goods will continue to Europe. According to European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, IMEC will cut delivery times to the continent by 40%. Some analysts believe shipping time from India to Europe could eventually shrink to just three days.

This trade revolution also serves another purpose: reducing dependence on the Suez Canal and outcompeting China. New Delhi’s ambitions are clear. It wants to challenge Beijing in global trade-and it’s willing to align itself with Washington, Riyadh, and Jerusalem to do it. The U.S. has already promised F-35 fighter jets to India, which in turn will ramp up imports of American LNG and crude. Bilateral trade is expected to hit $500 billion by 2030.

And while China has poured billions into acquiring European ports-Piraeus in Greece is now majority-owned by COSCO-India is making its own moves. The Adani Group recently acquired the Israeli port of Haifa, a key node in IMEC. The corridor’s impact on Europe is already visible: Italy, once an enthusiastic participant in BRI, now signals it will pull out of the Chinese initiative altogether.

But perhaps the most remarkable aspect of IMEC is its political feasibility. The Abraham Accords-signed in 2020-2021-laid the groundwork for normalization between Israel and several Arab states, including the UAE and Bahrain. That momentum made IMEC possible. The I2U2 group (India, Israel, UAE, U.S.) further institutionalized the effort, even establishing a joint tech fund between Israel and the UAE.

Abraham Accords signing ceremony. Representatives of Bahrain, Israel, the United States, and the United Arab Emirates posing for a photograph on the South Lawn of the White House after signing the Abraham Accords, Washington, D.C., September 15, 2020

This is how new orders are born-not only through military might, but through trade lanes, digital highways, and shared economic vision.

To be clear, the competition is far from over. China remains deeply entrenched in Latin America, Africa, and Southeast Asia. But Washington and New Delhi are mounting a serious challenge. The U.S. is investing in railway construction in Angola, port upgrades in Ecuador, and telecommunications infrastructure across the Indo-Pacific.

And so, a new great game is underway-not in the mountains of Central Asia, but along the rail tracks of Arabia and the ports of the Mediterranean.

This time, India is not a passive player. It is shaping the board.

But as economic rivalry intensifies, so too does the risk of escalation. The central question is no longer who dominates the routes of trade-but whether this strategic competition can avoid crossing the line into global conflict.

Share on social media