For January 27, International Holocaust Remembrance Day, Edward Rowe tells the story of three heroic men from the Caspian Region who helped save the lives of hundreds of Jewish families.

Railroad tracks leading to Auschwitz, in German occupied Poland, where thousands of Jews were systematically killed by the state. Image: Black Metal Train Rails/Pexels

January 27th marks the International Day of Commemoration in Memory of the Victims of the Holocaust. Today people remember the millions systematically murdered and persecuted by Nazi Germany and its collaborators during World War Two.

Those observing the commemoration will likely be aware of heroic figures like Oskar Schindler, the German industrialist believed to have saved over a thousand Jewish people from the genocide by hiring them in his factories in Nazi-occupied Poland and elsewhere.

They might not, however, have heard the names Abdol Hossein Sardari, Selahattin Ulkumen, and Hamza Sadygov. Among Western audiences, this is quite understandable: after all, two of the men’s homelands were not even major players in the Second World War.

Sardari’s country, Iran, had tried to stay neutral but later declared war on Nazi Germany in 1943. This came after British and Soviet forces invaded and essentially occupied Iran around two years earlier as part of plans to secure its valuable oil fields and supply routes.

Ulkumen came from neighbouring Turkey, which refrained from picking a side for most of the war, only joining the Allies (the British Empire, the US and the Soviet Union) in February 1945. The country saw out the remaining months of the conflict without ever firing a shot. Indeed, Turkey would probably never have joined the war had the Allies not made it a precondition for joining the United Nations. Only Sadygov, from Agdam, Soviet Azerbaijan, played an active part in the war.

All three men would go on to play important parts in rescuing victims of the Holocaust.

Sardari belonged to a well-off aristocratic family and was related on his mother’s side to the Qajars, a dynasty with Azerbaijani roots that ruled Iran from the eighteenth century until 1925.

Abdol Hossein Sardari was an Iranian diplomat known as "the Iranian Schindler." Image: Wikimedia Commons

Sardari took up a diplomatic posting with the Iranian Foreign Service in Paris and was there when Nazi Germany occupied the city in 1940. As elsewhere in Europe, the Nazis enacted antisemitic policies, and France’s Jews were forced to wear a yellow star, singling them out for discrimination and mistreatment.

Worse still, the Nazi regime started detaining Jews in concentration camps. Deportations from France to the infamous Auschwitz death camp started in 1942.

As these changes took hold, Sardari used his diplomatic privileges to support Iranian Jews who called Paris home. He played the Nazis at their own game, picking holes in their racist ideology to gain concessions. The Nazis saw themselves as being at the top of a racial hierarchy, as a “master race” which they called “Aryan.” In contrast, other groups that they deemed “inferior,” such as Jews, Romany people, and people with disabilities, were known as “Untermensch” or “sub-human.”

The Nazis did, however, classify Iranians as Aryans. Sardari exploited this. He wrote to the Nazi authorities claiming that Iranian Jews had no blood ties to the European Jews but were ethnically closer to other Iranians. Therefore, he argued, they should be classified as Aryans who just happened to practice Judaism.

His case was considered in Berlin and resulted in Iranian Jews being exempted from wearing the yellow star. This made it easier to blend in.

Sardari also handed out 500-1000 Iranian passports, which whole families could use. This act is believed to have saved an estimated 2000-3000 primarily Iranian Jews and also their non-Iranian spouses. This sometimes involved ignoring superiors and falsifying documents. He even disobeyed orders to leave France after Iran declared war on Germany, continuing his efforts, despite losing his salary. He later died in exile in the UK in 1981, but his work meant that thousands of Iranian-origin Jews – many now in America – are alive today.

Like Sardari, Selahattin Ulkumen was a diplomat. He represented Turkey on the Greek Island of Rhodes, then home to a roughly 1,800-strong Jewish community that included Turkish citizens. The Nazis occupied the island in 1943 and began deporting local Jews to concentration camps the following year.

Turkish diplomat and consul Selahattin Ülkümen served among an 1800-strong Jewish community in Rhodes during WWII. Image: Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs

Ulkumen complained to General von Kleeman, a German military commander, and demanded the release of around 40-50 Jews with connections to Turkey on the grounds that Turkish citizens were not subjected to deportation. After Ulkumen threatened an international incident, the commander relented and released them. In fact, they were not all Turkish citizens, but Ulkumen claimed non-citizens with Turkish spouses had equal rights to citizens. It was not technically accurate, but the Nazis bought it. In one dramatic case, Ulkumen ensured the husband of a Turkish woman was rescued from mainland Greece having already boarded an Auschwitz-bound train.

Ulkumen himself was interned after Ankara cut ties with Berlin in August 1944 and was not released until May 1945, when he returned to Turkey. He received numerous medals for his efforts and was commemorated in multiple exhibitions, both before and after his death in 2003.

Unlike Ulkumen and Sardari, Hamza Sadygov was no diplomat. He served as a Soviet intelligence officer at the Battle of Stalingrad, WWII’s deadliest battle at what is today the city of Volgograd, Russia. The fighting ended with a Soviet victory in February 1943, marking a turning point in the war. The six-month-long battle was brutal, leaving around two million casualties.

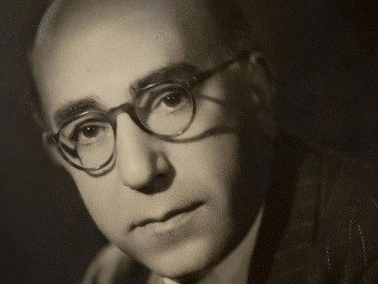

Hamza Sadygov, who was an Azerbaijani intelligence officer, saved dozens of Jewish families and captured one of the close associates of Hitler. Image: Embassy of the Republic of Azerbaijan to the United States

Ahead of the Nazi surrender, Sadygov and his men were tasked with capturing the German General Rodenburg, who had a reputation for personally murdering Jews and even testing biological weapons on Jewish children and pregnant women.

Sadygov lost many soldiers during the attack on Rodenburg’s headquarters. He was even shot by Rodenburg while taking him prisoner, but the operation was a success and prevented the Nazi from committing future atrocities. During the battle, Sadygov rescued Jewish captives held in Rodenburg’s cellar before pursuing the general. He is credited with saving over thirty Jewish families.

Sadygov returned to a hero’s welcome in his native Agdam in 1945 and was nominated Hero of the Union – Gold Star, the Soviet Union’s highest honour for heroism. According to his son Firdovsi, Sadygov received thank you letters from grateful Jewish people for his actions and had close Jewish friends. He lived in Agdam until his death in 1964, aged 49.

Here at the Caspian Post, we hope readers will pass on the stories of these heroes of the Holocaust so that others might remember them too.

Share on social media