Mark Elliott remembers his first visit to the Caspian and ponders the apparent contradictions of seaside resorts where attractions include rain and the chance to swim fully dressed.

In season, Iran’s Caspian beaches are packed with domestic tourists. Image: Zurijeta/Shutterstock

In 1984 I was a clueless, penniless student. On something of a whim, I’d bought a one-way ticket from London to Karachi (via fabulous Damascus as that was the cheapest route). Any idea I might have had of taking my own short walk in the Hindu Kush, Eric Newby style, had been restricted to Pakistan since the Soviet invasion that had removed Afghanistan from the old ‘hippy route.’ Instead,

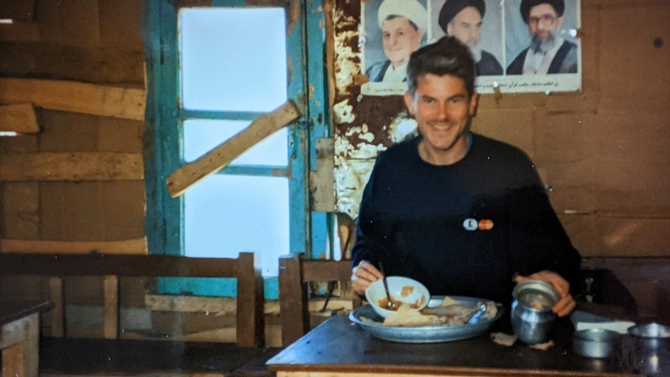

At the time, just five years after the revolution that had toppled the Shah, Iran was being portrayed as being fearsomely anti-Western. Apparently, when my parents told their friends that I was soon to be in Tehran, the reaction was akin to the announcement of terminal cancer. Of course, the reality couldn’t have been more different. I was blissfully unaware of ta’arof, the Persian form of politeness that means one should repeatedly turn down surreal levels of generosity from strangers. As a result, I shamelessly accepted invitations to eat with, stay with and even holiday with the kind, delightful Iranians I met. So it was that a fellow called Nasser, my long-suffering host in Tehran, announced that he could take me to the seaside. ‘Sure,’ I said when I should have been refusing the absurdly generous suggestion. We jumped into his nostalgic

Happiness, they say, is life without expectations. The Iranian Caspian is fascinating, but a sun-soaked paradise it certainly isn’t. The first thing I discovered was that for people from the parched desert regions of Central Iran, one of its great attractions is the rain. A humid micro-climate makes the southwestern Caspian region unusually lush: there are even rice paddies in the hinterlands. The rain and the cooling billows of sea-mist were, for Nasser at least, a key draw. And clearly, he was not alone.

The route west from Chalus, where the mountain road reached the sea, did not wind between the idyllic fishing villages and palm trees of my imagination. Instead, this was a traffic-choked series of main roads through town after busy town that almost merged into one gigantic low-rise sprawling suburb. “The seaside is popular, so everyone wants a holiday home here,” Nasser explained neutrally. Though of relatively modest means, Nasser’s family had their own little getaway on the edge of Ramsar. It was cozy and a fairly short drive from the ‘beach.’ Forget golden sands, the patch we found had a muddy consistency. The persistent drizzle didn’t encourage us to linger, though it was fascinating to watch a couple of ladies venturing into the shallow waters fully clad in black chador.

I should have realized that this place would not have had a desert island vibe had I thought about it. After all, Ramsar is most famous as the place where, in 1971, the international community signed the eponymous Ramsar Agreement on wetlands protection – one of the world’s earliest environmental pacts.

My initial disappointment was assuaged considerably as the mists cleared, and it became apparent how unique Ramsar’s location was – pinched closely between the Caspian and a lush backdrop of forested mountain slopes. This was most visible in the area around the 1937 Grand Ramsar Hotel[1], which had once been very exclusive and grand indeed with its orange groves and tree-lined avenue leading down towards the sea.

Another highlight here proved to be the fabulous food. To my surprise, local cuisine was not fish-based but instead focused on the remarkable bounty of fresh fruit and vegetables so prevalent in this fertile region - especially aubergine. Oh! The garlic-super-charged taste of mirza ghasemi (egg-aubergine-tomato dip) and the creamy-smoky poetry of kashke bademjan (walnut-eggplant paste with kaskh yogurt-whey). The dreamy flavours quickly put in context all the uncontrolled construction that had marred the region architecturally.

On our final day at the coast, we visited a former palace of the deposed Pahlavi royals. It was not quite a museum, and the visit felt a little surreptitious - like being shown around a mansion by nervous yet self-righteous squatters. The interior style proved an odd mix of faded neo-classicism and 1960s James Bond. The way the guide talked about the place suggested that the appropriate response in each room would be a gasp of disbelief to the depravity of the royal family’s decadent lifestyle. In reality, the place didn’t seem excessively opulent compared to stately homes in the UK.

Afterwards, I asked Nasser what he thought about the Shah and his entourage. Were they really the indulgent, opium-smoking tyrants that the guide had portrayed?

“Frankly, I hated him,” Nasser replied. “I hate Khomeini too, of course. I never wanted an Islamic Republic. But the difference is that I can tell you that. If I had expressed any opposition to the Shah, I’d have been in jail.”

[1] Though a little worse for wear in 1984, the hotel was extensively restored in 2017 regaining much of its former grandeur.

Share on social media

Mark Elliott remembers his first visit to the Caspian and ponders the apparent contradictions of seaside resorts where attractions include rain and the chance to swim fully dressed.