Crimean Tatars (2)

Ivan Aivazovsky's painting depicting the arrival of Catherine II in Feodosia. The Crimean Khanate was annexed to Russia in 1783. Image: Wikimedia Commons

The Tatars of Crimea are a Turkic, Muslim yet truly European ethnic group whose culture and current political plight we outlined here. To understand the complexity of the group’s relationship with Russia, there’s a lot of history to get a handle on. It’s an understatement to say that the people’s experience of Russian rule has been painful, but those horrors only started in the 18th century. Before that, there’s plenty more to the story.

Crimea’s ancient history is long and complex, going back to a rich Scythian culture around the 4th century BC. Golden artifacts from the Scythian period are among many strands of the international tussle that has been fought since Crimea’s 2014 annexation. A Dutch museum was ordered to return an extensive borrowed collection to Ukraine rather than to their home institutions in Russian-controlled Crimea.

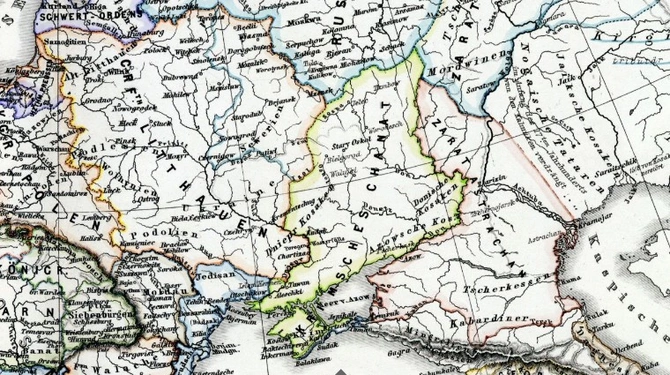

Crimean Khanate (the yellow area mid-image) as it was in 1550. Image: Wikipedia

The geographical area of Ukraine that is currently under Russian occupation[1] and administration is not so very different from the region that medieval maps show as constituting the Khanate of Crimea. This entity, which lasted from the 1440s to 1783 – albeit within frequently varying borders – was one of the most important Muslim remnant states to emerge after the break-up of the empire of the Golden Horde, itself a fragment of the great Mongol empire founded by Genghis Khan. Crimean Khans traced their lineage and thus their legitimacy to a direct Genghis Khan bloodline. As with the Ottoman Empire, to which the khanate was allied and sometimes subordinate, Crimean society was relatively open-minded regarding minority religious freedoms, but the economy relied heavily on capturing and selling slaves. The unfortunate victims were ‘harvested’ from the steppes to the north, with around 2000 a year typically exported via Italian middlemen through the Genoese-founded port of Caffa (now Feodosiya).

Gustav-Feodor Pauli’s 1862 portraits of a group of Crimean Tatars. Image: Wikipedia

After losing the Russo-Turkish War of 1768–1774, the Ottoman Empire accepted that the Crimean Khanate would no longer be under its official suzerainty. The khanate became officially independent but, in reality, a neutral protectorate of Russia. Then, in 1783 Russia marched in and unilaterally annexed the area altogether. No, 2014 was not the first time!

Over subsequent years, Crimean Tatars suffered a ‘slow, steady disenfranchisement’ as outsiders migrated into the area. From the 1830s, Tsar Nicholas I endorsed a report aimed at pushing non-Slavic native inhabitants of the empire to “speak, think, and feel Russian.” Nonetheless, the peninsula was still overwhelmingly populated with Tatars during the Crimean War of 1853-6. That period is best remembered in the West for the Charge of the Light Brigade and the nursing heroics of Florence Nightingale. However, the conflict was a truly bloody affair between Russia and an Anglo-Franco-Turkish alliance that left some 650,000 dead. Caught in the middle, the Tatars of Crimea – Turkic-speaking Muslims – were considered en masse to be a fifth column by the Russian authorities[2].

Meanwhile, Russian landowners took over ever more land, turning once-free farmers into serfs. Over the coming decades, an unofficial ‘cultural war’ pushed some 200,000 Crimean Tatars – over 60% of the area’s remaining population – to leave their homeland for the relative safety of the Ottoman territories. A big spur was that pious Muslim men wanted to avoid facing forced enlistment in the Tsar’s ‘Christian’ army.

For those who remained, however, the 1870s saw a rekindled sense of Crimean Tatar identity thanks to writer-publisher Ismail Gaspirali (Ismail Bek Gasprinskiy, 1851-1914). His mother was from a notable Tatar family, his father was a former lieutenant in the Russian army, and Ismail himself was a remarkable character who at one point worked for the writer Ivan Turgenev in Paris. He travelled to the Ottoman Empire and was inspired to see that entity in the throes of reforms. Ismail became an educational reformer and founded Tercüman (meaning ‘The Translator’), Crimea’s first Turkic-language newspaper. Such was his importance that on his death, he was buried beside the tomb of Haji Giray, the first ruler of the Crimean Khanate.[3]

Seen here on an address signboard is the ubiquitous yellow-on-blue ‘M’ that is generally associated with Crimean Tatar consciousness. Known as the taraq tamğa trident, it was introduced as state insignia of the Crimean Khanate in the 14th century and is itself derived from an earlier motif hailing from the Golden Horde. Image: Wikimedia Commons

1917 was a chaotic period in much of Eurasia, WWI heading towards a climax at the same time as Russia’s imperial structure crumbled in two major revolutions. In Crimea, there was a brief window where Russian power waned, allowing a Tatar-led if multi-ethnic local government to declare itself the Crimean People’s Republic. Numan Çelebicihan (1885-1918) became president and wrote the national anthem,

During WWII, Hitler’s forces took Crimea in October 1941 as part of a move to control the Black Sea. Three years later, the Red Army retook the region, and soon after, brutal purges began. It’s well known that Stalin’s administrators deported a dozen ethnic groups from the Caucasus, but they also removed the Crimean Tartars. The peninsula’s entire Turkic population, then numbering over 190,000, was shipped out

The movie Haytarma/Qaytarma/

Officially the reason for the deportation was that Crimean Tatars had been ‘traitors’ for not having resisted German occupation. While some 20,000 Tatars had ‘volunteered’ to join one of eight pro-Nazi Crimean battalions, the accusation ignores the fact that those folks, languishing in concentration camps, had received a stark choice: to don a German uniform or face almost certain death in captivity. According to Crimean Tatar nationalist leader Edige Kirimal,[4] Stalin’s ‘traitor’ label for banishing the Tatars was a spurious excuse part of a “long-prepared plan devised by Moscow to clear the peninsula completely of the Turkish population.”

Whereas many other ethnic groups – like the Chechens and Kalmyks – were allowed to return to their homelands in the 1950s, for the Crimean Tartars, like the Meskheti Turks, the exile continued far longer. Indeed in a botched attempt to further detach them from their roots, the people became re-labelled as ‘Tatars who formerly lived in Crimea’ while being encouraged to ‘re-join’ other Tatars – a crazy idea as the different Tatar groups had vast cultural differences. There was also an attempt to create a special area of Uzbekistan as a vaguely imagined new homeland. Known as the ‘Mubarek Republic’ or ‘Mubarek Zone,’ from the small city at its centre, it was situated in a bleakly undeveloped area. Those Crimean Tatars who agreed to be relocated were promised positive discrimination and schooling in their mother tongue. However, the plan was a complete failure,[5] and the few Tatars who did move to Mubarak were generally “stigmatized as traitors to the national cause.”

In 1987, some daring Crimean Tatars took a ‘Motherland or Death’ campaign to Moscow, a highly risky move for the era. It produced the largest protest on Red Square since the Russian Revolution of 1917 but had no immediate results. Only from November 1989, with the USSR soon to fragment, were Crimean Tatars officially allowed to return to their homeland, a decision perhaps encouraged by the aftermath of the Fergana Massacre, a bloody riot in Central Asia between Uzbeks and Meskheti Turks. While that generally didn’t affect Uzbekistan’s Crimean Tatars directly, it caused many minorities to feel insecure.

Over subsequent years, some 250,000 of the former Crimean deportees and their descendants would return to their ancestral homeland. And although many thousand left in the wake of the Russian annexation of 2014, the majority remain on the peninsula. Especially since the 2022 Russian (re)invasion of Ukraine, the hitherto little-known plight of the Tatars has become something of an international geopolitical football, as we describe here.

[1] as of May 2022 encompassing Crimea, the Donbas and the north coast of the Sea of Azov.

[2] Recent scholarship examining surveillance documents from the era suggests that there was no evidence of significant wartime collusion between Crimean Tatars and the Ottoman-Turkish military.

[3] The grave would be destroyed in 1944 as part of the deportations and efforts at the erasure of any Tatar presence in Crimea.

[4] As quoted by Brian Glyn Williams in The Crimean Tatars: From Soviet Genocide to Putin's Conquest, chapter 6

[5] Except perhaps for the Uzbekistan party bosses who ‘fleeced’ Moscow of the funds required to build infrastructure in one of their backward provinces under a spurious series of justifications

Share on social media