Russia's war in Ukraine is just the latest conflict to afflict one of Europe's least know ethnic groups - the Crimean Tatars.

Image: AndriiKoval/Shutterstock

“Wow – it’s almost totally understandable,” – exclaimed an Azerbaijani friend. He was listening to a report about the situation in Ukraine by Crimean journalists, exiled from their land since the Russian takeover in 2014. The language they were using was Crimean Tatar. Could it really be so similar to Azerbaijani, we wondered? I took a few random paragraphs of text from their agency’s website and pasted them into Google Translate’s Azerbaijani option. Almost all of the results came out with intelligible English. Remarkable.

But who are these Tatars of Crimea? Shamefully belatedly, I was suddenly inspired to learn more about “one of Europe's most misunderstood Muslim ethnic groups.” Despite a fascinating and tragic history, the people had been relatively little studied by Western scholars before the Russian annexation of 2014. Ever since, however, their story has been prey to politicization by both pro- and anti-Russian voices, a situation that’s become all the more pronounced since the start of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine this year.

Today the Crimean Tatars consider themselves comparatively homogenous, bound together by their appalling experience of the later Soviet period. However, historically and genetically, the group is very diverse. Their Turkic language is patched together from once separate regional dialects of Nogayli-Kipchak and Oghuz, plus a recent admixture of Anatolian Turkish. Yet, even this is probably an oversimplification. Like a mini-Caucasus, Crimea’s southern mountains were once seen as a reservoir for peoples of very varied linguistic backgrounds.

…their Turkic language is patched together from once separate regional dialects of Nogayli-Kipchak and Oghuz plus a recent admixture of Anatolian Turkish.

Ismail Gaspirali, the great force behind Crimean Tatar consciousness in the 1870s, had a motto, "Unity in Language, Thought and Deed." For his newspaper, he essentially crafted a hybrid Crimean Turkic language that mixed simplified Oghuz/Ottoman Turkish with a wide sprinkling of Kipchak Turkic vocabulary. This allowed for a tongue that was aimed to be understandable right across the Turkic world but at the very least managed to forge a linguistic bridge between the “Nogai-speaking Tatars of the Crimean steppe [and] the Oghuz-speaking Tat Tatars of the Crimea's southern coast.”

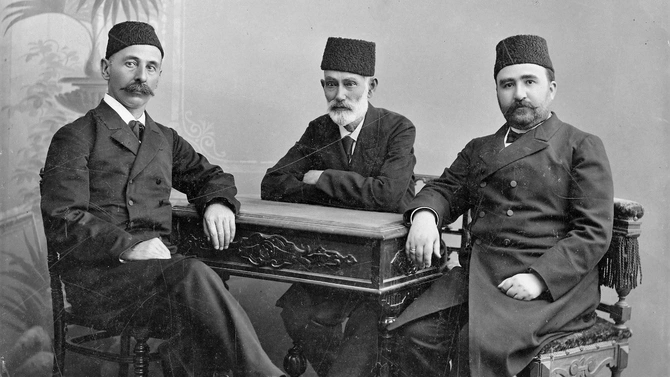

Ismail Gaspıralı (L), journalist Hasan bey Zardabi (C) and politician Alimardan Topchubashov, in Baku, Azerbaijan, 1903.

In the early 1990s, a 31-letter script was designed for use with the language based very closely on Turkish Latin, albeit with an extra “Ñ/ñ.” Within Ukraine, that alphabet’s use for Crimean Tatar was officially side-lined until 2021, when the Ukrainian cabinet changed its mind and proposed that all Tatar educational establishments should switch to it from September 2025. The move was fascinating if very belated, given that by this stage, Crimea itself had been annexed by Russia for many years. So critics might consider the announcement somewhat tokenistic.

The name Tatar is in itself a confusing one. It was once a catch-all phrase commonly used by Europeans for most Turkic Muslim peoples they encountered as they headed east. Some groups retained or re-assumed the term in the period of Soviet national conscious-building, most notably the Siberian Tatars and Volga Tatars (who now refer to their republic as Tatarstan). However, neither group is directly related to the Crimean Tatars.

As with the language, so too the cultural similarities – notably, some Crimean Tatar

The Crimean Tatars have had remarkable history worthy of an article of it's own. However, that has been marked by several attempts to marginalize them in their own homeland - generally, by Russia. The worst by far was in 1944 when the whole ethnic group en masse was deported to Central Asia and the Urals in appalling conditions. Many thousands died. Yet, in 1955, historian Walter Kolarz pointed out that this was by no means the first assault on Crimean Tatar identity. He suggested that "the liquidation of the Crimean Tatars as an ethnic group and their removal from their Crimean homeland by the Soviet government was but the last act of a long process which had started when Empress Catherine II established a Russian Protectorate over the Crimea in 1774 and annexed it in 1783."

There seems to be a fair degree of truth to this. Although other deported peoples like the Chechens, Ingush and Kalmyks were allowed to return to their homelands after Stalin’s death, the Crimean Tatars were not officially allowed back until 1989. By the 1990s, a return trickle had become a flood. Still, while newly independent Ukraine accepted almost 250,000 returnees, the Tatars’ ancestral lands had long since been taken over by Russian or Ukrainian families or converted into big resorts. Many returnees were thus marginalized, living in makeshift settlements with poor sanitation despite some financial help from the UNHCR. Some, who moved too late to make the most of Soviet-era border fluidity, found themselves stateless or with papers identifying them as Uzbek citizens making it doubly hard to find legal work in the new Ukraine.

Questions of cultural diversity and language protection simmered in Crimea until 2004, when frustrations snowballed into widespread demonstrations following the stabbing of a Tatar man by a gang of Ukrainians. Moods softened in the wake of Ukraine’s 2005 Orange Revolution when a new, more liberal government in Kyiv allowed a limited power-sharing deal to create a degree of official representation for the group. In 2006, a Simferopol TV company started broadcasting in Crimean Tartar with programmes including interviews with victims of the 1944 purges

Women walk past graffiti depicting Russian President Vladimir Putin, dressed in a Judogi and sitting next to a girl, on the facade of a children's health centre in Yalta, Crimea, August 19, 2015. The painted word reads "Ours". REUTERS/Pavel Rebrov

The ethnic-Russian majority of Crimea was happy with the 2014 annexation, as reflected in a convincing referendum result. However, for Crimean Tatars, the picture was far less clear. While the community had not been particularly well treated by Ukraine, for many, a new Russian-controlled future raised the potential spectre of history’s many bad experiences returning. Around 20,000 Crimean Tatars are thought to have left soon after annexation. However, for most others, the draw of a motherland to which they had so recently returned was stronger than any qualms over political control.

Things started badly when the new authorities drowned out speeches at the Tatars’ 60th-anniversary marches commemorating the 1944 deportations and started arresting anyone who publically disputed Russian annexation, often describing such a posture as the ‘crime’ of ‘violating Russian state integrity.’ Some who still dared to protest, like Reshat Ahmetov, were tortured and ‘disappeared.’

Independent Ukrainian media was prevented from operating in Crimea. That included the Crimean Tatar outfit ATR, which the new leadership described as an “enemy element.” For the same basic reasons, the Mejlis was dubbed an ‘extremist group’ when it refused to endorse Russian control. Its building was commandeered, and the secretariat fled to Kyiv. Human Rights Watch noted increasing signs of persecution of Tatars in Crimea in 2016-17, while the painful historical issue of the Soviet-era Tatar deportations gained some traction internationally as the subject matter of Ukraine’s 2016 Eurovision winning song,

While a crackdown continues on Crimean Tatar activists, Russia tries to point to high-profile infrastructure investments that it has made in the region, hoping perhaps to win those who might have been less enthusiastic about the annexation. These include two new power stations and the road-rail link across the Kerch Strait. The latter heralds new connectivity with Russia for those in Eastern Crimea. However, by international law, as Crimea remains de jure part of Ukraine, the bridge is in complete contravention of Ukrainian border sovereignty.

The new Kerch Strait Bridge

For Crimean Tatars, one of the most symbolic post-annexation constructions has been Simferopol’s vast new Akmescit Cathedral Mosque complex (Akmescit is the Tatar name for Simferopol). Construction started in 2015 and is now almost finished. The mosque had originally been planned two decades ago, but permission was revoked in 2008, resulting in protests. Its completion allows pro-Russian Tatars to give a very tangible example of ways in which Kyiv proved to have done less than Moscow for the community.

However, the Tatar community remains under pressure. In 2021 Refat Chubarov, the Mejlis leader who fled Crimea in 2014, was tried in absentia by a pro-Russian court in Simferopol in 2021. He was handed a six-year prison sentence on charges of “organizing mass riots” and challenging Russia’s territorial integrity (i.e., not recognizing the annexation). In August 2021, the Council of Europe (the EU’s human rights organization) reasserted its call for, amongst other things, a repeal of Russia’s decision to curtail the Crimean Turks’ Mejlis.

Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine started in February 2022, things have become more challenging still for Crimean Tatars. Of the thousands who had

Further, Tatar ‘activists’ were imprisoned in March 2022 under the accusation of being part of Hizb ut-Tahrir, a non-violent pan-Islamic group that is legal in Ukraine (as well as in the US and UK) but banned in Russia (also in Germany and much of the Middle East).

Crimean Tatars had been amongst the founder members of UNPO (the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization). Since 1991 that organization has criticized the government of Ukraine for failing to give Tatars sufficient autonomy. Nonetheless, according to a 2022 UNPO statement, “at no point did the Crimean Tatar people suffer as they have done since the illegal occupation by the Russian Federation.”

In an open letter published at the start of the Russian invasion of 2022, the World Congress of Crimean Tatars[1] stated that “Crimean Tatars will not kneel, Ukraine will not surrender.”

However, for ordinary Crimean Tatars, a 2019 interview with a BBC reporter may give a more realistic sense of the general mood: a resident suggested that life within Russia was not especially better or worse for average folks than that within Ukraine. Actually, citizenship was of little real concern to her: “I don't care if we're with China! The most important thing is that there is no war.”

For many Crimean Tatars, what really counts above all is simply living on their ancestral lands, a land that most families spent generations fighting to return to. A land that’s as beautiful as it is disputed.

[1] Speaking for 183 Crimean Tatar civil society organisations in 16 countries

Share on social media