The Safavids are often associated in Western minds with the 17th-century architectural wonders of Isfahan, Iran. But their roots were Azerbaijani and throughout their long rule, the language used by their bureaucracy was a form of Azerbaijani Turkish.

This now-renowned image of Shah Ismayil was amongst the portraits of key world figures copied from rare 1520s manuscripts by painter Cristofano Dell’Altissimo at the request of Cosimo I de’ Medici in the 1550/60s. Image: public domain

Of all the various imperial dynasties which have left their mark on today’s Iran and Azerbaijan, few are as significant as that of the Safavids. Most significantly, this era (approximately 1501 to 1736) saw the establishment of Shi’ite Islam[1] and the modernization of warfare techniques. Yet if you describe their realm as a ‘Persian Empire,’ you can expect a roar of disapproval from Azerbaijanis and other Turkic groups who are swift to point out that the Safavids originated in Ardebil, a city in one of the Azerbaijani regions of today’s Iran. More importantly, the most prominent Safavid ruler, Shah Ismayil, wrote poetry in the form of Azerbaijani Turkish and is said to have favoured Turkic speakers over Persians at his court in Tabriz.

Ismaiyl’s move to Shi’ism and his break with the Sunni caliphate put the Safavid Empire on a collision course with the Ottoman Empire, leading to the pivotal battle of Chaldiran (near Maku in Iran’s West Azerbaijan province). Ismayil’s army lost, he was personally injured (but escaped), and the Ottoman army briefly occupied Tabriz. However, Ismayil’s army later pushed them back to recapture its capital.

The site of the battle of Chaldiran. Image: Wikimedia Commons

The dynasty survived and made diplomatic overtures to the Habsburgs to help keep the Ottomans in check, but as the Safavid rulers realized the vulnerability of Tabriz - being so close to the border with the Ottoman Empire—Ismayil’s successor, Tahmasib (Tahmasp), moved the capital to Qazvin, in another majority Azerbaijani Turkic speaking region. Around 50 years later, the capital moved again under Ismail’s great-grandson, Shah Abbas I—arguably the greatest Safavid ruler of all. This relocation was to the central Iranian city of Isfahan. However, although Isfahan is in a Persian-speaking region, Azerbaijani Turkic remained the court language, as we shall see. But first, let’s go back to the dynasty’s spiritual roots in the 13th century.

The man for whom the Safavid Dynasty was named is Safi-addin Ardabilli. He was born in 650AH (1252/3 CE) and became one of his era’s great Sufi spiritual teachers. Safi appears to have been a remarkable individual fluent in several languages. Much of what is known of his life and genealogy is due to a book called the Safvat as-safa. Originally written around 25 years after his death, the book is now known in two rather different versions—having been reworked centuries later once the Safavids’ adoption of Shi’ism made some of Safi’s essentially Sunni-based doctrines a little discordant to the state narrative. There is also some disagreement about Safi’s ethno-linguistic background,[2] though such worries are highly anachronistic when referring to a religious teacher in the 13th century. What is more relevant is to examine his spiritual lineage, which can be traced back very clearly to the Lankaran/Astara area of what is now Azerbaijan.

Sheikh Zahid Gilani’s portrait and tomb. Image: Wikimedia Commons

Safi arrived in the Lankaran area as a follower of Sheikh Zahid Gilani (aka Tajaddin Ibrahim/Tacəddin İbrahim, 1215-1300) and would go on to marry Zahid’s daughter Bibi Fatima. Zahid was himself a highly respected Sufi ‘saint’ whose growing influence had led to increasing friction with the Shirvanshahs, rulers of the Shirvan region to the north. They failed in several attempts to have him assassinated, and he lived a very long life, dying aged 85 at Siyavar (just south of Lenkoran). His original tomb was moved many years later due to the rising level of the Caspian Sea, which left the area flooded in the 1650s, and a new version was erected in Hilekaran/ Hilya Karin (now renamed Şıxəkəran), the very place in which Safi-addin is reputed to have first met Zahid. The Soviets destroyed that structure, but a simple brick replacement was restored in 2006.

Sheikh Zahid’s mausoleum in Şıxəkəran following its 2006 reconstruction. Image: azertag.az

Sheikh Zahid drew his spiritual lineage from Sheikh Jamaleddin, whose move to Butasar (now known as Pensar) was arguably the most significant reason that so many of the Gilani spiritual teachers ended up based in this southern region of what is now the Republic of Azerbaijan. Jamaleddin’s once highly revered mausoleum in Pensar was also demolished during the anti-religious era of the Soviet Union, and though locals secretly maintained a small shrine there after Stalin’s death, the current modest replacement only dates from the 1980s.

Gateway to Sheikh Jamaleddin’s mausoleum site. Image: sirat.az

During his lifetime, Safi-addin had nurtured Zahid’s local spiritual order—the Zahediyeh—into a major religious organization within Sufi-Sunni Islam—the Safaviyeh. Control of this group passed to Safi’s son Sadr al-Din Musa/Sheikh Sadraddin (1305-1391), who consolidated the movement with the approval of the great warrior-ruler Timur (Tamerlane) and founded the magnificent shrine to his father that is now Ardabil’s Unesco-listed centrepiece.

The Safi-addin Mausoleum Complex at Ardabil has been expanded many times over its history, becoming a place of pilgrimage for the early Safavids and their holy forebears. Image: Wikimedia Commons

The Safaviyeh passed to his son Khvajeh Ali/Hoca Ali, grandson Sheikh Ebrahim/Ibrahim and great-grandson Sheikh Junaid. Under the latter, the group’s message made a remarkable shift, turning away from one of mystic Sufi-Sunni asceticism to that of military force and a proselytizing ‘ghulat’ form of Shiism. In this new form, imams were seen as divine—including Junaid himself. According to Sunni scholar Ruzbihan Khunji, “the bird of anxiety laid an egg of longing for power in the nest of [Junaid’s] imagination. Every moment he strove to conquer a land or a region.” This mixture of physical aggression and apparent religious heresy led him to be banished from Ardabil. He initially moved west into the Ottoman Middle East and then, after gathering a major following of mostly Turkic devotees, settled in Shirvan (today’s Azerbaijan), where his presence caused friction with the ruling Shirvanshahs. The upshot was a 1456 battle at Hazra on the south bank of the Samur River that now forms the Russia-Azerbaijan border. Junaid was killed, but the momentum of his movement was only partially slowed.

Sheikh Junaid’s 1544 mausoleum at Hazra was built under the guidance of his great-granddaughter around a century after his death. Image: Wikimedia Commons

Based again in Ardabil, Junaid’s son Heydar continued in his father’s footsteps, pushing Shi’ism with military muscle and a strong belief in his own divinity. It was Heydar who started the custom amongst Safaviyeh warriors of wearing scarlet headgear[3], leading to their common moniker, Qizilbash (Red-heads). The name would come to apply to a highly heterodox coalition of many different tribes, all brought together under the spiritual leadership of the Safaviyeh. However, the majority spoke forms of Azerbaijani-Turkic: Rumlu, Shamlu, Ustajlu, Afshar, Qajar, Tekeli, Zulkadar, Bayat, Baharl, Qaramanli etc, the widely used suffix -li/-lu suffix underlining Oghuz/Turkic linguistic lineage. Although over time, the Qizilbash would grow to include people from an ever wider range of backgrounds, including Talish, Persian, Lurish and Kurdish speakers, their lingua franca was Azerbaijani Turkic.

Image: ageofempires.com

Heydar and the Qizilbash helped his kinsmen, the so-called ‘Aq-Qoyunlu’ (White Sheep) confederation, another Azerbaijani-Turkish speaking dynasty, to rise to prominence across much of Eurasia in the second half of the 15th century. However, like his father, Heydar’s campaigning in Dagestan led to conflict with the Shirvanshahs, and having sacked their capital, Shamakhi, Heydar was captured and executed, his severed head being taken to Tabriz.

Sheikh Heydar’s headless body was originally buried in Meshginshahr, where an 18m tomb tower still stands, though his remains were later moved to Ardabil by Shah Ismail and reunited with their skull. Image: Wikimedia Commons

Initially, control of the Safaviyeh passed to Heydar’s eldest son ‘Soltan Ali’ (aka Ali Mirza, 1469-94), the first Safavid leader to take the title Padishah (great king). By this stage, he was a possible challenger for the regional power of the Aq Qoyunlu ruler, who put him to death. However, his younger brother Ismayil (1487-1524)—still only a child—would soon avenge him at the head of a Qizilbash army.

By lineage, Ismail had a fair claim to rule the region. Quite apart from his illustrious father, Heydar, his mother, Halima Beyim, was the daughter of Aq Qoyunlu ruler Uzun Hasan, and his maternal grandmother had been the daughter of the Emperor of Trebizond, a Pontic Greek offshoot of the Byzantine Roman empire based on what today is Trabzon in northeastern Turkey. Still, his ascendancy was far from assured, and he had to fight to assert control over the vast territories that he would come to control. Avenging the deaths of both his father and grandfather, 14-year-old Ismayil’s first major victory was the startling defeat of Shirvan (northeastern Azerbaijan)

In a battle near Shamakhi in December 1500, in which 7000 Qizilbash troops managed to decimate a Shirvanshah force that was almost four times the size. Ismayil moved on to grab Baku, but his military successes attracted the nervous attention of the then Aq Qoyunlu ruler. He sent an army north to attack Ismayil’s forces, but once again, the Qizilbash managed to overcome seemingly impossible odds at the July 1501 Battle of Shahrur, rapidly moving south and taking Nakhchivan then Tabriz, where he declared himself Shah, at the age of 14.

Shah Ismayil initially seemed unstoppable, coming to command an empire of vassal kingdoms that stretched way beyond Iran, as far afield as Uzbekistan, Kuwait, and Georgia. The expansion of the Safavid lands was halted to the West by the Ottomans, who eventually beat the Ismayil’s army comprehensively in 1514 at the turning-point Battle of Chaldiran thanks to greater numbers and the use of then state-of-the-art heavy artillery that Ismail lacked. Nonetheless, Ismayil had already launched the Safavids as empire builders, bringing in Shi’ite traditions that, to this day, give Iran such a distinctive spiritual outlook. Yet despite sharing some of the ‘divinely inspired’ confidence of his forebears, it appears from some of his poetic writings (under his pen-name Khatai) that he remained surprisingly self-deprecating:

Khatai’s of a pedant’s school

Sufi by heart and should know much

Yet tell the truth I’m but a fool

Ismayil’s poetry still resonates with beauty and wisdom to modern Azerbaijani readers. A great example is Şah mənəm (I am King):

Allah-allah, deyin, ğazilər,

Ğazilər, deyin, şah mənəm.

Qarşu gəlin, səcdə qılın.

Ğazilər, deyin, şah mənəm.

Uçmaqda tuti quşuyam,

Ağır ləşkər ər başıyam,

Mən sufilər yoldaşıyam,

Ğazilər, deyin, şah mənəm.

Nerdə əkərsən, bitərəm,

Xanda çağırsan yetərəm,

Sufilər əlin tutaram,

Ğazilər, deyin, şah mənəm.

Inevitably, translation loses the nuances of the original Azerbaijani-Turkish and can’t repeat its rhythm and mesmerising rhyme. However, even in English, the poem still reflects a sense of a great man contemplating the powers that appear to have fallen upon him.

God-God, say, ghazis[4],

Ghazis, say, I am the king.

Come and prostrate yourself.

Ghazis, say, I am the king.

I am a parrot in flight,

I am a head of heavy (strong) infantry,

I am a friend of Sufis,

Ghazis, say, I am the king.

I sprout, where planted ,

I come, when I’m called

Sufis, I will hold your hand,

Ghazis, say, I am the king.

Although generations of Safavid rulers moved their power centres ever further from the dynastic heartlands, Azerbaijani Turkish remained language of the court, the military, and the provincial administration as well as of the official correspondence of the Shah. This was widely attested by the reports of numerous European travellers, diplomats, and missionaries who visited the Safavid state. Perhaps we should not be surprised by this fact—after all, it was the mother tongue of the Qizilbash tribes, which constituted the backbone of the state.

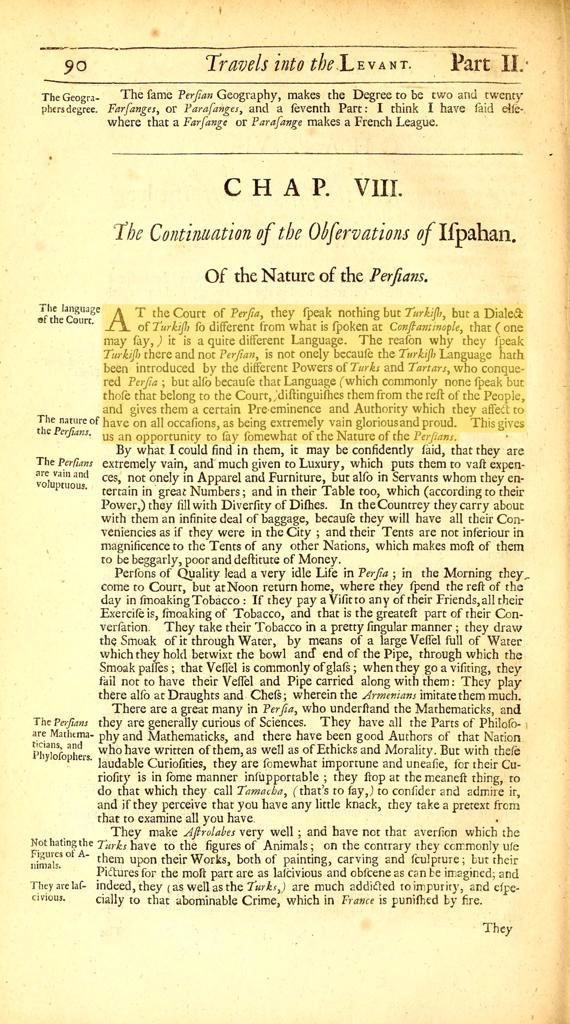

One first-hand source is Jean de Thévenot (1633-1667) in his posthumously published Travels into the Levant (English translation 1687, part II, chapter 8), who recalls that:

In the court of the Persians, they speak nothing but Turkish, but a dialect of Turkish so different from what is spoken at Constantinople that one may say it is a quite different Language. The reason [is partly] because the Turkish language hath been introduced by the different Powers of Turks and Tartars, who conquered Persia.

Image: archive.org

So, was this rarefied form of ‘Turkish’ actually a precursor of today’s Azerbaijani? Many scholars believe so, even if those encountering it used different names for the tongue (including Qizilbashi, Turquesco and Turki).

And evidence suggests that such Azerbaijani-Turkish was used right up until the end of the Safavid Dynasty’s rule, i.e. the 1730s at the hands of Nadir Shah[5], himself a hailing from the Afshar tribe of the Qizilbash coalition.

As we have seen, the Safavids contributed a lasting series of crucial legacies in the Caspian region. It was thanks to this originally Ardabil-based dynasty that Shia Islam took root in what is nowadays known as Iran. And it was the Safavids who popularised the use of Azerbaijani-style Turkish in poetry as well as in military and bureaucratic administration. These links are especially important for today’s Azerbaijan: it reminds the world that just because the country only became a nation-state in 1918[6] doesn’t mean that Azerbaijani history started in the 20th century. To this day, the Safavids and many previous dynastic empires, such as the Ag-Goyunlu, Kara-Koyunlu, Shirvanshahs, Atabegs-Eldegiz, and others, continue to inspire a sense of Azerbaijani pride and the Safavid rulers—especially Shah Ismayil ‘Khatai’—resonate intimately with a sense of Azerbaijani identity.

[1] and more specifically, “Twelver” Shi’ism in which the twelfth imam (divinely ordained leader) to follow the Prophet Mohammad (PBUH) is believed to have disappeared in a mysterious process of ‘occultation’ from which he will one day reappear. Other Shi’ite forms trace different lineages for their imams.

[2] typically cited as Kurdish

[3] Originally, the hats were in 12 segments (or ‘gores’), signifying the 12 imams of twelve Shia Islam

[4] Sometimes auto-translated as ‘veteran’, a ghazi was a heroic Muslim warrior fighting for religion in the early days of Islam

[5] Nadir Shah and the Afshars are typically referred to as ‘Turcomans’ in history books. That is not a synonym for Turkmen in the modern sense but was used in earlier times to refer to Muslin Oghuz Turks, So although Nadir Shah was born in what’s now northeastern Iran, it’s not far fetched to suggest that he too probably spoke a language close to Azerbaijani Turkic.

[6] for two years and then not again until 1991

Share on social media