Photo: tj.usembassy.gov

Independence is not only about the formal sovereignty of a nation but also about economic structural constraints. In Central Asia, this economic structure is what ANBOUND’s founder Mr. Kung Chan refers to as the “Soviet structure”. Mr. Chan points out that, even today, and perhaps into the future, this “Soviet structure” continues to deeply influence the long-term stability and security of the Central Asian region, The Caspian Post reports citing Eurasia Review.

A significant feature of the Soviet-era economic system was its strong planned nature. In the Central Asian region, Kyrgyzstan is an agricultural country, with agriculture being the backbone of its economy, accounting for 36% of its GDP. Uzbekistan is the world’s sixth-largest cotton producer and the second-largest cotton exporter. According to past data, 28% of Uzbekistan’s workforce was in agriculture, which contributed 24% to its GDP. Tajikistan is the poorest country in Central Asia, with a low GDP; in 2006, its GDP was only 80% of what it had been in 1990. The country’s economy is also heavily reliant on agriculture and livestock. Thus, several key countries in the Central Asian region, influenced by the “Soviet structure”, have their economies and productive forces focused on water-intensive agricultural sectors, and this situation has not fundamentally changed.

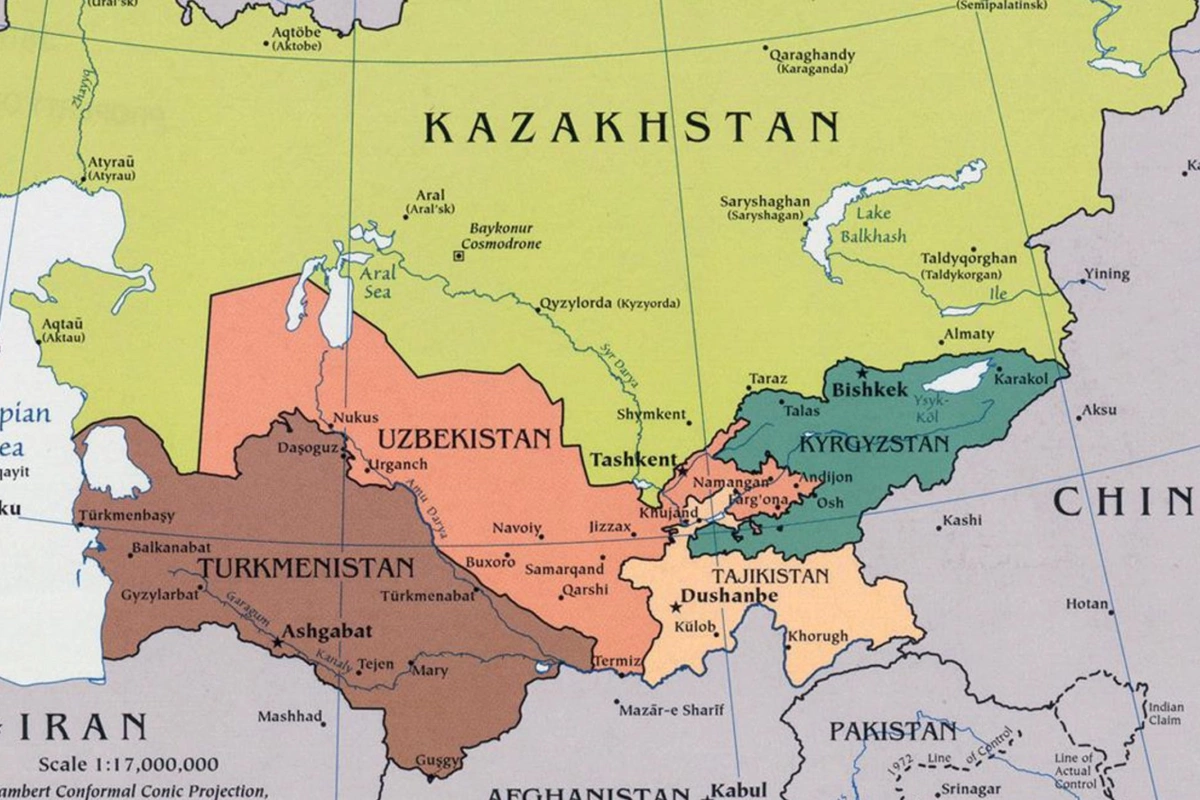

However, since the Soviet era, water scarcity has always been a significant challenge. The five Central Asian countries are located deep in the heart of the Eurasian continent, making it difficult for oceanic moisture to reach the region. As a result, the average annual precipitation in Central Asia is generally below 300 millimeters. In areas near the Aral Sea and the deserts of Turkmenistan, the annual rainfall is even as low as 75-100 millimeters. Only in the mountains and the southern slopes of the Fergana Valley does precipitation increase slightly, reaching 1,000-2,000 millimeters. Along with the low rainfall, evaporation is exceptionally high. For example, the annual evaporation rate from the Amu Darya Delta can reach 1,798 millimeters, which is 21 times the local precipitation.

The five Central Asian countries not only face water scarcity, but the distribution of water resources is also extremely uneven. The southeastern part of Central Asia is home to the towering Tian Shan Mountains and the Pamir Plateau, where glaciers and snowfields serve as the most important sources of water. During the spring and summer, the melting ice and snow feed the Syr Darya and Amu Darya rivers, which flow from southeast to northwest through the Turan Plain, passing through deserts and steppes, and eventually drain into the Aral Sea. The Syr Darya, which originates in the Tian Shan Mountains, is 2,212 kilometers long and flows through Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and Kazakhstan. Its basin area is 219,000 square kilometers, with an average annual runoff of 33.6 billion cubic meters. The Amu Darya, on the other hand, originates in the Hindu Kush Mountains, stretches 2,540 kilometers, and flows through Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. Its basin area is 465,000 square kilometers, with an average annual runoff of 43 billion cubic meters.

Due to differences in the origins and lengths of the countries through which they flow, the two major rivers exhibit imbalances in terms of both flow and hydroelectric potential. In terms of flow, 43.4% originates in Tajikistan, 25.1% comes from Kyrgyzstan, 2.1% is from Kazakhstan, 9.6% is from Uzbekistan, and 1.2% comes from Turkmenistan. The upstream countries of Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan contribute 68.5% of the flow. As for hydropower resources, Tajikistan accounts for 70%, and Kyrgyzstan accounts for 21%, totaling 91%. It is clear that both Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan hold a dominant position in terms of both flow and hydroelectric resources.

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the five Central Asian countries frequently clashed over water resources. Since 1990, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan have fought over land and water in the Osh region, resulting in 300 casualties. In 1992, due to disputes over cross-border rivers between Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan sent airborne troops to the Kyrgyz border, using force to pressure Kyrgyzstan. In the winter of 2000, Kyrgyzstan had to increase the water discharge from the Toktogul Reservoir to meet its domestic electricity needs after Uzbekistan stopped supplying natural gas. This resulted in large areas of Uzbekistan’s cotton fields turning into swamps. In the summer of 2008 and 2009, management failures at the Toktogul Dam caused water shortages in Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, leading to prolonged electricity shortages in Kyrgyzstan. The ensuing instability in Kyrgyzstan ultimately led to the downfall of then-President Kurmanbek Bakiyev, highlighting the highly political nature of water resource issues.

In recent years, disputes over water resources among the five Central Asian countries have been rarely heard of. The five countries have also repeatedly expressed their intention to strengthen coordinated management and use of water resources, as well as to enhance consultation on multilateral platforms such as the United Nations. The situation regarding the water crisis seems to be showing signs of easing. However, researchers at ANBOUND believe that, based on a combination of historical and current factors, the water crisis in Central Asia is far from being truly alleviated. In the current and next 3-5 years, the water crisis will continue to disrupt the stability of the region’s situation.

First, the basic situation of the water crisis in Central Asia has not undergone any real change.

As for the basic water resource situation in the five Central Asian countries, the state of water scarcity and the uneven distribution of water resources has not changed in any meaningful way. This inevitably means that the scarcity of water resources and the competition for them will not see any real easing.

Due to economic development, the water crisis in the five Central Asian countries continues to worsen. The natural population growth rate in these countries is high, and the population structure is young, hence there is a strong and constant demand and consumption of natural resources. Rapid population growth means that there is a decline in per capita resource availability, and the shortage situation is becoming increasingly prominent. At the same time, in recent years, these countries have been actively attracting foreign investment, especially from China, to develop manufacturing industries, with plans for factories such as BYD’s. The call for building data centers is also growing. Industrial production and data computing both require large amounts of water, which exacerbates the already limited water resources in the five Central Asian countries.

Moreover, water pollution in Central Asia has been increasingly severe over the years. Data shows that in 2018 alone, sewage flowing into the Amu Darya River accounted for 35% of its total flow, with an even higher proportion in downstream Uzbekistan. Ecological deterioration means that the already scarce water resources are even less available for human use.

Secondly, there has always been a lack of a strong and comprehensive mechanism for coordinating water resources and addressing the water crisis between the five Central Asian countries. During the Soviet era, through the construction of a series of water infrastructure and coordination of electricity resource distribution, the Soviet Union carried out a series of resource allocations and division of labor among the five Central Asian countries, establishing a water resource distribution mechanism between upstream and downstream regions. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the original coordination mechanism no longer existed, and water resource allocations, once an internal issue, became an international one.

To fill the order vacuum created by the dissolution of the Soviet Union, in October 1991, the five Central Asian countries signed an agreement on cooperation in joint management, use, and protection of interstate sources of water resources. This agreement decided to establish the Interstate Commission for Water Coordination (ICWC), whose main responsibilities included water resource allocation, water body operation and water quality monitoring, and the design and repair of hydraulic facilities in the Syr Darya and Amu Darya river basins. However, the ICWC was unable to intervene in the domestic water policies of the countries, ultimately becoming an organization that only provided water resource information to the countries. Furthermore, the ICWC was not trusted by the other four Central Asian countries, as its personnel was largely from Uzbekistan. The repeated calls by the five Central Asian countries at international forums to address the water crisis in the region also highlighted the weakness of their internal coordination mechanisms. This lack of an effective regional leadership mechanism to address and resolve the water crisis makes it difficult to prevent the issue from fermenting and worsening. At the ICWC conference held at the end of April 2024, after experts from the five countries expressed their views, they have yet to reach a consensus, and an effective coordination mechanism remains elusive.

Furthermore, international forces have long been hindering the efforts of the five Central Asian countries to address the water resource crisis. In recent years, international NGOs in Central Asia have become increasingly active, and most of these organizations have Western backgrounds. When it comes to environmental issues related to water resources, multinational NGOs often focus on aspects such as environmental protection and cultural heritage preservation. For instance, the Kyrgyz government planned to exclude the Chatkal River floodplain from the Besh-Aral State Nature Reserve to build a series of hydropower plants. The “Rivers Without Boundaries” coalition issued a call to the UNESCO World Heritage Committee and the International Union for Conservation of Nature, urging the Kyrgyz authorities to halt the plan. Environmentalists have also expressed concern about the Kyrgyz government’s approval of gold mining and infrastructure development in the protected area. In response to Kazakhstan’s new reservoir construction plan at the end of last year, relevant NGOs have argued from various perspectives that the plan is not feasible, and have organized petitions from local citizens to interfere with the process.

In recent years, the five Central Asian countries have actively sought to attract Western capital, while the influence of international NGOs has steadily grown. The obstructive actions of these NGOs could undermine the efforts of the five countries to tackle the water crisis, further intensifying the situation.

In November last year, the Eurasian Development Bank of Kazakhstan released a report stating that the five Central Asian countries will face a severe water crisis by 2028-29. In February this year, some analyses pointed out that due to increased irrigation demand, outdated infrastructure, and decreased water flow, the water consumption in the five Central Asian countries has risen sharply, surpassing the capacity of the main rivers, and the water crisis is imminent. Uzbekistan and Tajikistan even upgraded their river monitoring equipment in mid-February 2024 to closely monitor changes in flow. In this context, the lack of an effective coordination mechanism, coupled with the disruptive actions of international NGOs, will deepen the existing water crisis, potentially leading to regional conflict or even instability.

The Soviet planned economy shaped Central Asia’s focus on agricultural production, but this “Soviet structure” has been severely impacted by water scarcity. Although the countries have gained independence in terms of national sovereignty, their economies remain tightly bound to water resource issues. This structure has not been loosened, as all the countries are still reliant on the basins of the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers, meaning they remain structurally interconnected. As long as the countries in Central Asia cannot break free from this “Soviet structure”, their independence in terms of national governance will only apply to political power, while their economic integration and shared dependence on water resources will continue to make the region a potential place of conflict and discord.

ANBOUND’s founder Kung Chan pointed out as early as ten years ago that the competition for water resources would become a significant cause of future conflicts. In the five Central Asian countries, where water resources are scarce and unevenly distributed, the combined effects of numerous adverse factors will make this issue highly prominent and will continue to disturb the stability of the regional situation.

Share on social media