Azerbaijan - Iran - Culture

Making movies has changed a lot over the years, and Azerbaijani Turks in Iran have been around for all of it. Image: yotanan chankheaw/Shutterstock

The widely anticipated release of Tarlan, a film made by Mohammad Hosseini, is the latest of several big-name Iranian Azerbaijani movies to emerge in recent years. Given Iran’s large Azerbaijani-Turk population, it is understandable that the country’s cinema, like many other cultural fields, has been influenced by Azerbaijanis. However, it has been a struggle. For most of the 20th century, Iranian filmmakers of any linguistic group were obliged to make their movies in Farsi. And even in that language, Azerbaijani Turkish accents were all too often used to suggest that a character had lower status. It has been a long time coming, but that has started to change significantly in the last few years.

The country’s first cinematograph was introduced in 1900 by Qajar Shah Mozaffar al-Din, who had spent his younger years as titular governor of Azerbaijan Province. After 1925, when Reza Shah Pahlavi took power, non-Persian languages were officially outlawed in Iran, so early Azerbaijani-Iranian films were written and spoken in Farsi.

Qajar Shah Mozaffar al-Din (ruled 1896-1907) is generally remembered as an incompetent ruler better suited to pleasure than management. Still, under his rule, one of the positive things was the arrival in Iran of the first cinematograph. Image: public domain

A key figure in cinema and theatre linking the two Azerbaijans was Samad Sabahi (1914-1978). Born on the then Russian-side of the border in Ganja and graduating in theatre studies in Baku, Sabahi emigrated to Tabriz in 1932. There, and in other important cities of Iranian Azerbaijan, he played an important role in the development of theatre, notably through his 1941 play Od Gelini (Bride of Fire). 1941 was when the British and the Soviets informally divided Iran between them under the guise of WWII. One side effect was a greater sense of cultural freedom for non-Persian citizens. As the war ended and the Red Army withdrew from northern Iran, the USSR tried to retain a degree of leverage by supporting two breakaway republics. The bigger of these was an autonomous ‘People’s Government’ under the Azerbaijan Democratic Party of pro-Soviet Jafar Pishevari. During this short window of opportunity (November 1945 to December 1946), Sabahi founded several theatrical groups and staged many Tabriz productions in his mother tongue. These included the classic Uzeyir Hajibeyli operetta Arshin Mal Alan and the play Qacaq Kerem, a historically based folktale of the courageous son of a peasant revolt leader. He spends 15 years as a fugitive after fleeing a blood feud in Western Azerbaijan.

In 1946 Samad was joined in temporarily autonomous Tabriz by his brother, the prominent writer Ganjali Sabahi, who had till then been in Soviet Azerbaijan. However, the Azerbaijan People’s Government fell later that year, and the ban on performances and publications in Azerbaijani was reinstated. Ganjali Sabahi, accused of being an illegal immigrant, was sent to a two-year exile in a ‘deprived village’ of the Lorestan region. Samad Sabahi’s unsanctioned productions of the previous year meant that he too was punished – banned from artistic activity for three years. After that, he was allowed to work again but only on the condition that he leave the Azerbaijani region of Iran.

Now based in Tehran, Samad Sabahi took to cinema, directing a film version of Arshin Mal Alan and in 1953, Mashhadi Ebad, another satirical musical comedy also based on a 1910 Hajibeyli original. However, all the words and even the song lyrics were performed in Persian, so even though the movie is said to be the first to make a direct connection between the two Azerbaijans, the film is probably less celebrated today than the 1956 version made in Baku in the original Azerbaijani.

Ganjali Sabahi (On the left) and Samad Sabahi (On the right). Image: public domain

After the 1979 Islamic Revolution, Azerbaijani cinema in Iran entered a new period. Several film companies were established in the Iranian Azerbaijani cities of Urmia (Orumiyeh) and Tabriz, with films directed by Rasoul Malakalipour, Yadollah Samadi, Yadollah Navasari, and Hassan Mohammadzadeh. However, cultural inequality and racial discrimination continued, and the use of the Azerbaijani language was still not a possibility for many years.

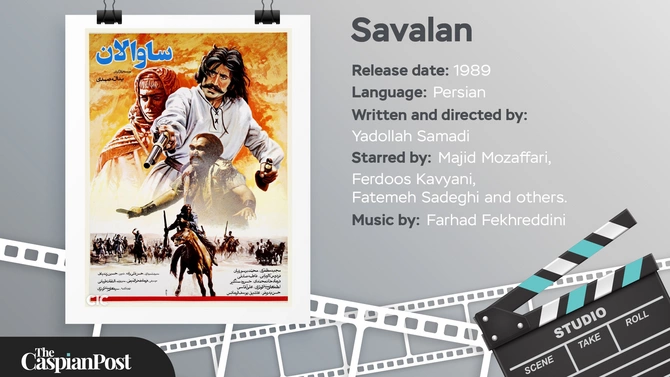

Instead, directors like Yadollah Samadi (1952-2018) focused on Azerbaijani culture, especially folklore. Such movies included Dümrül (1993), a heroic tale based on sections of the Turkic epic Dede Qorqud,Savalan (1989), the story of Azerbaijani-Turkish villagers resisting bandit attacks, and the tyrannical tragedy Saray (1997). All were initially filmed in the Persian language, but eventually, Saray was dubbed into Azerbaijani Turkish – a move widely welcomed by Azerbaijani audiences in Iran.

In the 90s, there was an increasingly intense fight against linguistic and cultural discrimination against minorities in Iran. Meanwhile, the regaining of independence by the Republic of Azerbaijan on the north side of the Aras River helped raise cultural awareness among Azerbaijanis in Iran. As the decade proceeded, Iran at last witnessed Azerbaijani Turkish language film production and TV programming for channels in Tabriz, Ardabil, Urmia and Zanjan.

Though broadcast on television rather than on the big screen, Vüsal Günləri (The days of Unification), directed by Reza Siami, was the first such film. Then in 1995, cinemas screened Rahbar Ghanbari’s O (S/he), set in a village of the Ardabil region of Iranian Azerbaijan. It went on to win awards at many domestic and international festivals. A year later, Ghanbari headed north of the border to make Wishes about refugees in the Republic of Azerbaijan displaced by the First Karabakh War. Other Azerbaijani-Iranian filmmakers such as Hassan Najafi, Babak Shirin Sefat, Vahid Azar and later Ali Abdali all made feature films in the Republic of Azerbaijan and/or Turkey, but – apart from one of Ghanbari’s films – none of those movies were screened in Iran.

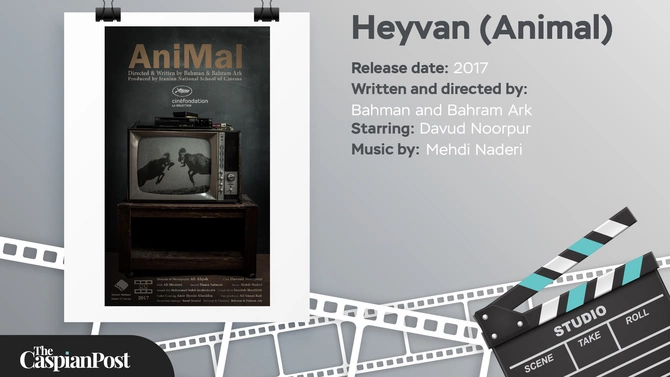

The situation was better for shorts. In the post-revolutionary years in Iran, short films became popular as the government attempted to nurture young filmmakers who could launch Islamic cinema. In the meantime, many young Azerbaijani Turks took advantage of this opportunity to enter the film industry and continue to make shorts in their mother tongue. Success stories include Reza Jamali, Ismail Monsef, Farhad Eivazi, Shahzad Qureshi and the Ark brothers (Bahman and Bahram). The latter’s AniMal investigates the limits of humanity in a 15-minute tale of a man ‘becoming’ a ram in an attempt to sneak across a border. It won several awards, including a second prize at the prestigious Cannes Film Festival in 2017.

Although serious barriers remain, Azerbaijani independent cinema in Iran is growing. Difficulties remain in finding investors, finding screening opportunities, and various bureaucratic problems. Still, there has been much progress in the number and quality of movies made in recent years, along with the freedom to celebrate the Azerbaijani language. These days, home-grown Azerbaijani-Iranian cinema offers a form of cultural resistance that helps preserve and re-honour the mother tongue.

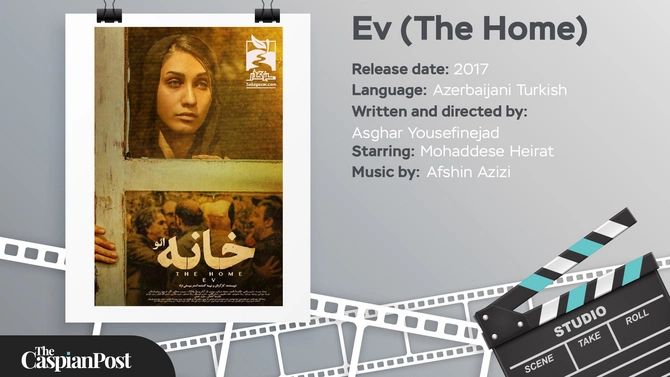

The 2016 feature film"Ev" (The Home), directed by Asghar Yousefinejad, attracted the attention of Iranian film critics. Produced in Tabriz in Azerbaijani Turkish with Persian subtitles, it hangs on the dilemmas of a traditional family. They want to bury their dead father but discover that his wish had been to donate his body to medical science. That’s problematic, it turns out, as it would reveal that his own daughter and son-in-law had murdered him. Ev won the Simorgh Zarrin and Simin awards for best screenplay and best film at Iran’s 35th Fajr Film Festival, along with the Netpak Award (Development of Asian Cinema).

The film’s success led to a flurry of activity for independent Azerbaijani-Iranian cinema. First, Ismail Monsef produced Kömür (Charcoal), in which a charcoal-burner’s son evades prison and escapes across the border into the Azerbaijan Republic, causing a spiral of tragic events for his father. Then Reza Jamali won the Asian Spirit award at the 2019 Tokyo Film Festival with Old Men Never Die. That’s a mesmerizing, if slow-paced tale of a man whose past life as an executioner has, he believes, frightened away the spirit of death and left the white-beards of the village immortal. It’s a benefit that they start to rue. The magnificent choice of very genuine old characters adds to a deadpan humour that feels like a darker take on Jaco Van Dormael’s Le Tout Nouveau Testament – albeit based in Azerbaijan rather than Belgium. You can get the idea from a 10-minute version that’s available online.

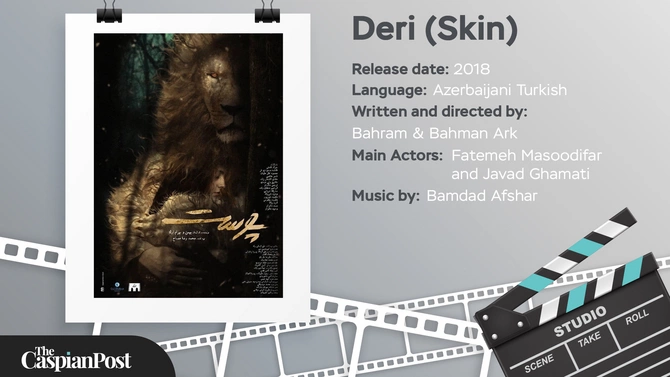

At the 2020 Fajr Film Festival, Nikki Karimi's Atabay was a prominent Azerbaijani-language success, while the Ark brothers' Deri (Skin), based on a theme from Azerbaijani mythology, won best movie and the best soundtrack in two categories. Very unusual for Iranian cinema, Deri is in the horror genre.

Released online in 2020, Tarlan is the latest movie to come out of Iran’s ever more vibrant Azerbaijani independent cinema movement. A social commentary, it revolves around a shepherd boy who seems to have a supernatural ability to predict when wolves are threatening his flock. He tries to persuade villagers that this is simply a learned skill, but they are convinced he has extraordinary powers and demand he work a miracle for them too. Trailers for the film have been widely shared on social media by Azerbaijanis around the globe suggesting that it will have a significant audience on both sides of the Araz River – in independent Azerbaijan as well as the Azerbaijani regions of Iran and well beyond. And to make it easier for international audiences, the pay-to-view online service is now available through an English language portal for just 15,000 Iranian Rials (around 40 US cents).

Share on social media