Made with technology a “good thirty years ahead of its time,” the Soviet MD-160 was a marvel in engineering and aeronautics. Maybe it was too ambitious: the last of its kind is beached as a tourist attraction on Dagestan’s Caspian sea shore.

“Lun,” the Caspian Sea Monster. Image: Vladimir Zhoga/Shutterstock

Ancient Beluga Sturgeon fish, 7m long and weighing well over a tonne, really did once cruise the Caspian – especially in the Volga Delta at the sea’s northern end. However, in this article, we’re not talking about giant fish, nor Loch Ness-style mythical dino-sightings. The real-life Caspian Sea Monster was, in fact, a popular nickname given to the

The ekranoplan developed from an idea by engineer Rostislav Alexeyev who figured that with the right configuration, a hydrofoil ‘boat’ could lift its foils out of the water altogether and simply fly using the lift effect of a cushion of air between short ‘wings’ and the surface of the water. From a military perspective, another significant benefit would have been that, unlike a ship, it was safe from underwater torpedoes, yet unlike conventional planes, it flew too low to be spotted by radar. This meant that it would have had a deadly potential as a missile-gunship defending the Soviet Caspian or Black Seas.

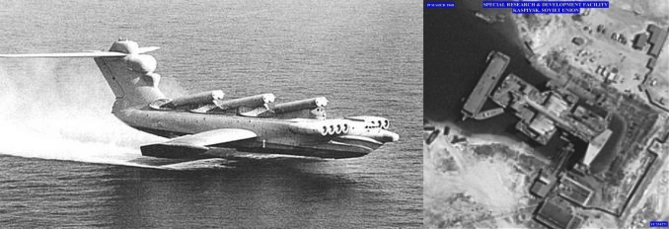

In 1967, a photo from US spy satellites showed the original KM ekranoplan in the harbour of Kaspiysk near Makhachkala in the Russian republic of Daghestan. The CIA dubbed the mysterious new craft KASP A and set off a sense of panic that the USA was getting left behind technologically. It has been suggested that the desire to get a closer look at the KM ekranoplan was the motivation behind the development of early unmanned spy drones through Project Aquiline.

Left: Glory days - The Lun ekranoplan in flight. Image: Soviet Navy. Right: The aerial spy photo of Kaspysk Harbour that first revealed to Western intelligence agencies that an ekranoplan ground-effect vehicle was being developed by the USSR. Image: US Government - National Reconnaissance Office

In reality, KASP A was having teething troubles, and after almost 15 years of testing and tinkering, the original prototype crashed into the Caspian in 1980.

By that time, Brezhnev had reduced funding for the project, but a smaller Orlyonok troop carrier was produced while a 73.8m ‘LUN’ prototype ekranoplan was developed as a fearsome weapon for launching undetected missile attacks on aircraft carriers. Produced through the classified ‘Project 903’ and codenamed the MD-160, one operational version went into service around 1987. However, the USSR had begun to implode by this stage, and funding dried up, so work on these super-expensive creations essentially stopped. In recent years, the principle of hydro-planes has re-emerged both as a useful form of transport in the inaccessible

The ekranoplan being winched inch by inch onto Derbent beach in October 2020. Image: J_K/Shutterstock

The one serviceable MD-160 remained based at Kaspiysk through the 1990s but eventually fell into disuse. A 2019

Share on social media