Hair flies wildly as dervishes perform trance-like ‘dances’ on the rooftops of a spectacular Kurdish stepped village. Welcome to Howraman Takht’s Pir Shalyar Festival in far western Iran.

Howraman’s most celebrated festival replays the legendary wedding of a hermit-healer. Image: IRNA

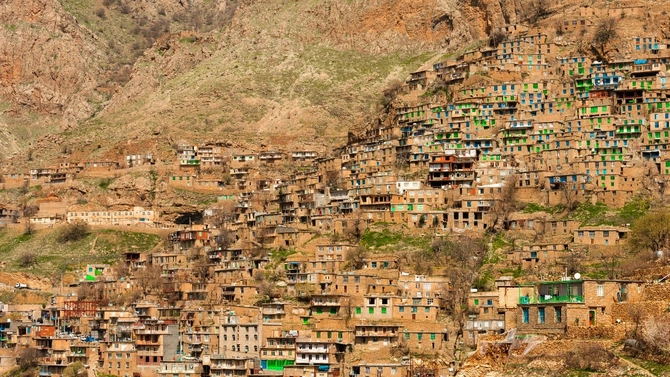

The oversized village of Howraman Takht in Western Iran is an architectural work of art with its earthen-coloured houses stacked almost organically up the side of a craggy hillside. They would be perfectly camouflaged against the dusty mountains were it not for arrays of blue- and green-shuttered windows staring out across the valley like hundreds of eyes. The slope is so steep that the roof of one house often forms the front yard for the house above. In this, it resembles the famous Gilani village of Masuleh in lush northwestern Iran, but unlike the latter, there is virtually no tourism here.

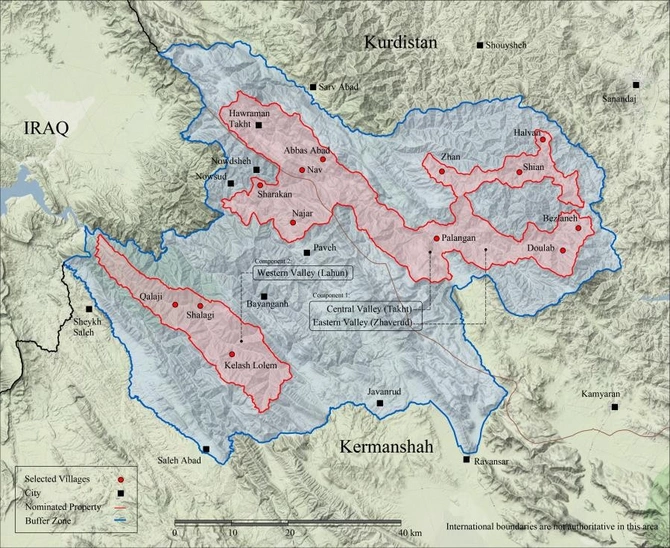

Yet the whole of the Howraman area is sprinkled with similarly memorable settlements - Takht simply means ‘head’ or main village. Culturally it’s hard to find anywhere in the world that’s more authentically Kurdish.

While most Kurds fall into one of two main linguistic sub-groups, i.e. Kurmanji and Sorani speakers, Howraman is home to the Hawrami people – part of the third, lesser-known subgroup, Gorani. Hawrami is considered the most ancient dialect, and it’s sometimes regarded as the classic literary language for Kurds in general, especially in poetry.

Given all this, it’s hardly surprising that the ‘Cultural Landscape’ of Howraman Valleys (also known as Uramanat or Avroman) has been listed by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site, albeit only since July 2021[1].

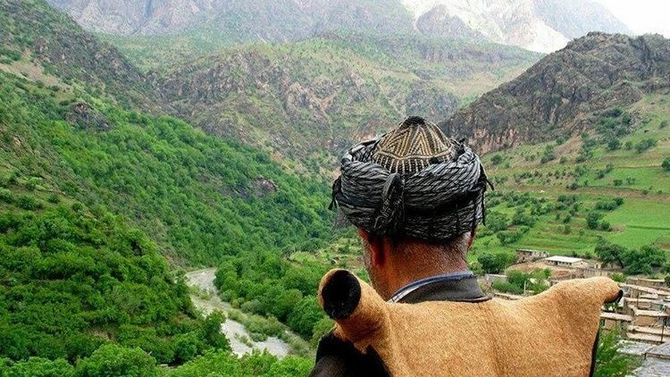

As you’ll find throughout much of this part of Iran’s Kordestan province[2], local men very often wear the typical Kurdish chokho-ranak suits with the super-baggy shalwar trousers and a pshten (cummerbund). Some also wear turban caps.

More specific to Howrami gents, however, is an archetypal winter waistcoat: the utterly distinctive faranji. Also known as a ‘kulabal’ (meaning short-sleeved), these come with eccentric shoulder extensions that create the impression of horns.

Faranji are typically made from rolled felt whose wool comes from the

The Pir Shalyar ‘wedding’ is one of Iran’s most mesmerizing annual festivals. The most visually striking feature is a Sufi dhikr ceremony watched by great crowds of people (almost exclusively men) crammed precariously onto the layered rooftops.

Another rooftop acts as de facto ‘stage’ where several percussionists beat the daf (a local form of large tambourine), and a chant leader rhythmically recites holy phrases.

Meanwhile, a line or circle of other men work themselves into a semi-trance, arms linked and together intoning keywords, most often the name of God – “Allah, Allah, Allah.” All the while, they bow rapidly up and down, some dervishes flexing with such force that their long hair flows wildly.

The festival has roots dating back at least 1000 years, and despite its Muslim overlay, it’s believed to have pre-Islamic roots. Travel guide publisher, Lonely Planet,

With large numbers of people descending on the village, which has fairly minimal commerce of its own,

Though the festival has several elements, the main “wedding” ceremony usually takes place over three days at the end of January. The exact dates vary annually: weather is a major factor as heavy snow can make organizing the event impractical.

Even if you can’t visit for the Pir Shalyar ceremonies, Horwaman Takht remains fascinating at any time of year.

And in March, the town hosts its own distinctive version of Nowruz.

[1] It’s Iran’s 26th World Heritage Site - the application for UNESCO status was first lodged back in 2007.

[2] as well as across the nearby Iraqi border

Share on social media