The idea of submerged cities has always fascinated the human imagination. Just think-right nearby, beneath your very nose, lie treasures that have remained silent for centuries! Eager to investigate this question as thoroughly as possible, we decided to interview a professional who has spent many years working in underwater archaeology.

Meet Alexander Volovik-a diver and native Bakuvian, belonging to the third generation of his family to live there. We met him in the Old City (Icheri Sheher) at a cozy café near an 11th-century mosque, and here is what he told us:

My grandfather moved to Baku in 1913 and worked as a manager at a printing house that belonged to Zeynalabdin Taghiyev. We lived in a house on Bolshaya Krepostnaya Street, formerly a 14th-century caravanserai. Forty other families also lived in our courtyard. My mother worked for many years as a primary school teacher at School No. 189, which is why in 1954 I started first grade there. During my youth, the interior of the Maiden Tower only had old wooden walkways in a terrible state of disrepair, so the tower was closed to visitors. An elderly man, Uncle Yunus, worked there as a guard. He kept pigeons on the observation deck, and my friends and I would steal his pigeons. We climbed up the exterior wall of the tower in the evening, gripping a gas pipe and stepping on the protruding stones in the masonry, stuffed the pigeons under our shirts, and climbed back down. We were quite the hooligans back then!

- Could you share more about what life was like in the Old City at that time? What unique sights, sounds, or customs shaped your childhood experiences?

- From my early childhood, I was enthralled by the sea and dreamed of enrolling in a maritime college. However, they only accepted applicants who were 18, and I was only 16. So I became a cabin boy on a hydrographic ship that conducted work for the Geophysics Institute, and I stayed on board until I was drafted. Since we spent months at sea, I was quite a negligent student, and it was only after joining the army that I realized the importance of studying! I served as a radio operator in the Baltic, in a closed city called Baltiysk, at one of the most well-equipped naval bases, originally built by the Germans. Our unit carried out special underwater operations, worked on raising sunken vessels, and provided assistance to submarines.

- What were some of the biggest challenges of working on special underwater operations in the Baltic? Were there any moments that particularly tested your courage or skill?

- Over time, thanks to my background in underwater sports from my maritime school days, I became a trainer-instructor at DOSAAF’s Marine School (the ‘Voluntary Society for Cooperation with the Army and Navy,’ a sports organization). During my work there, I trained around 400 divers. I served as the coach of the republic’s spearfishing team and as the assistant coach for underwater orienteering. Of course, this was quite an interesting job, but at a certain point I realized I needed to move on and so I became a professional diver.

- How did your experience as a trainer at DOSAAF influence your later work as a professional diver?

- For many years, I worked as the senior rescue diver at the Shikhovo-1 beach, and also at the Oil Rocks and Zhiloy Island. Within my section, there was a group of young people who founded the club ‘Nayada.’ We were so passionate about underwater research that we wrote a letter to Jacques-Yves Cousteau saying that here in Azerbaijan we were following in his footsteps and that we welcomed the dawn of a new underwater era for humanity. And Cousteau wrote back! He sent us an autographed photo and his business card. From that point on, for many years, we gathered on November 19 and took a boat to Vulf (Wolf) Island to celebrate Cousteau’s era.

- What was it like receiving a response from Jacques-Yves Cousteau himself? How did that motivate your underwater exploration efforts in Azerbaijan?

- At one point, I also collaborated with the Museum of the History of Azerbaijan, where Viktor Kvachidze (a well-known marine archaeologist, senior researcher at the Museum of the History of Azerbaijan, and the Institute of Archaeology at Azerbaijan’s Academy of Sciences) had created an underwater archaeology group. I participated in several underwater expeditions. One of these took place at the mouth of the Kura River, where we explored quarters of an ancient city that had sunk below the water’s surface. There was also a very interesting expedition to Svinoy Island (now called Byandovan). Incidentally, Stepan Razin gave it the name Svinoy [meaning ‘Pig’ Island], as he used that island to launch raids on Baku, where he fought the Persian fleet and burned it. We even found remnants of his boat there.”

- Why did he call it Pig Island?

- During Stepan Razin’s time, the water level was low. Wild boars would run there from other islands along the chain of rocky ledges and stones to drink water. But they were not the only creatures. The island is located near the Shirvan Reserve, which is home to many different animals. In its marshy areas, various rare migratory birds either spend the winter or nest. Apart from gazelles, you can also find nutria, steppe boars, hares, Caspian seals, wolves, jackals, foxes, and badgers. These animals drink seawater, which is not as salty as elsewhere, because this is where the Shirvan Canal and, further south, the Kura River flow into the Caspian. As a result, the water here is practically fresh.”

- What do you know about the submerged cities now scattered across the entire area of Baku Bay?

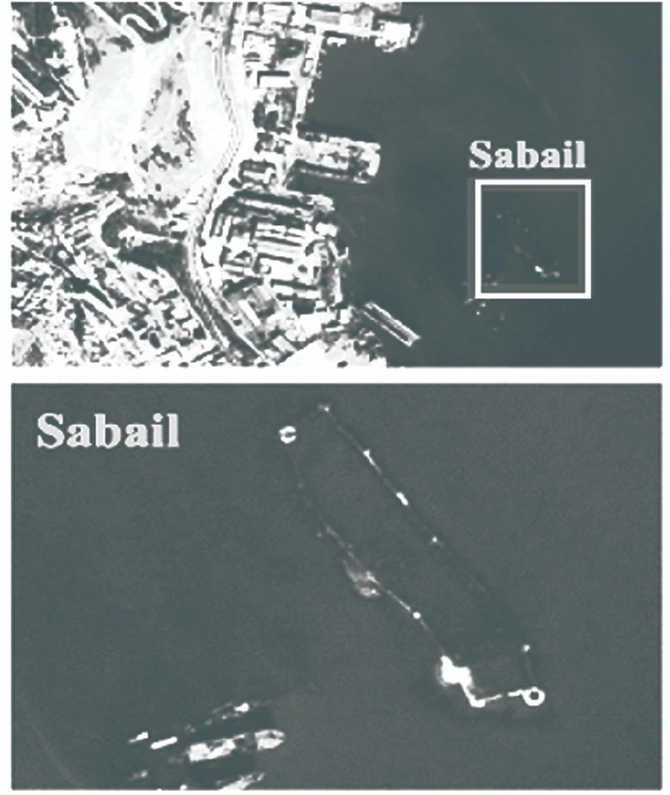

- My mother told me that when they were children, they were taken through an underground tunnel from the Maiden Tower that ran under the sea to the Sabayil Island. This is approximately the spot where the large Ferris wheel (known locally as the ‘Devil’s Wheel’) stands today. It used to be the site of a shipyard named after the Paris Commune. When I was about 13 or 14, I practiced rowing in that same area, and we would take our kayaks to the island. We saw ruins of walls and foundations of some structures. In 1965, DOSAAF’s sports section asked us to assist with underwater work to raise stones with inscriptions from that island. (Some of these stones are now on display in the Palace of the Shirvanshahs; others are kept in the National Museum of the History of Azerbaijan.)

That project did not last long because the area was heavily polluted with oil residue, and our coach eventually refused to continue. However, in the 1980s, I was fortunate to work again with Kvachidze, who, under the supervision of the Museum of the History of Azerbaijan, led research on submerged settlements using scuba gear at depths of 4-20 meters between the islands of Oblivnoy and Banka Pavlova, south of Banka Kumani, in the area of Plita Pogorelaya Banka, and along the Pirsagat rocky ridge. We surveyed the seabed and coastal strip from the settlement of Nord Ost-Kultuk to Cape Byandovan. Along the coast, we discovered remnants of a cultural layer whose archaeological material included coins, pottery, bricks, pottery nails, fragments of clay with traces of wicker and reeds, and bones of animals, birds, and fish. These dated no later than the 11th-14th centuries. On the bottoms of many fragments of glazed pottery and on the surfaces of dishes, there were stamps and inscriptions in Persian. Two of them mention a master named Yusif. The wide extent of this cultural layer led us to suspect the remains of a sizable medieval city submerged by the rising Caspian Sea. Later research uncovered two medieval urban-type settlements, provisionally called Byandovan-1 and Byandovan-2, which are about 20 kilometers apart. Dr. Rauf Mamedov, head of the Medieval History Department of the Museum of the History of Azerbaijan, and Viktor Kvachidze proposed identifying them with two medieval cities-Gushtasfi and Mugan.

- During these expeditions, what kind of technology or equipment did you use to study and recover these artifacts under such challenging conditions?

- Among the discovered artifacts were both plain and glazed pottery dating back to the 11th-13th centuries. Some of the fragments contained inscriptions in Persian-lines of lyrical poetry. So, there you have it, poetry from the underwater world! On Byandovan, we also came across a hearth containing charred grains, as well as a large accumulation of animal, bird, and fish bones. At one point, a colleague working off Severnaia GRES, around the lighthouse area, explored the seabed and stumbled upon the remains of an enormous frigate. It turned out to be a ship called Kuba, belonging to the Russian Geographical Society, dating to the early or mid-19th century. All in all, I must say that Absheron still has many undiscovered artifacts that are periodically revealed by the now-receding Caspian. I believe that future generations will be able to unearth a great deal more about our history, still hidden beneath our sea to this day.

Share on social media