All images: Ralph Fox

A century ago, in 1925, British historian, writer, and revolutionary Ralph Fox published People of the Steppes, a compelling account of his travels offering rare insights into the life and culture of the Kazakh people. Fox (1900-1936) was no ordinary observer.

A journalist, Marxist, and author of biographies on Lenin and Genghis Khan, he traveled through Soviet Central Asia in the early 1920s and spent his final years working at the Marx-Engels Institute in Moscow, where he wrote his last major tome, The Caspian Post reports citing The Times of Central Asia.

In the foreword to People of the Steppes, Fox states that his aim was not political propaganda but to record what he had witnessed. His observations, written as he journeyed through the steppe from the Orenburg region to the Aral Sea, provide a vivid portrait of nomadic life.

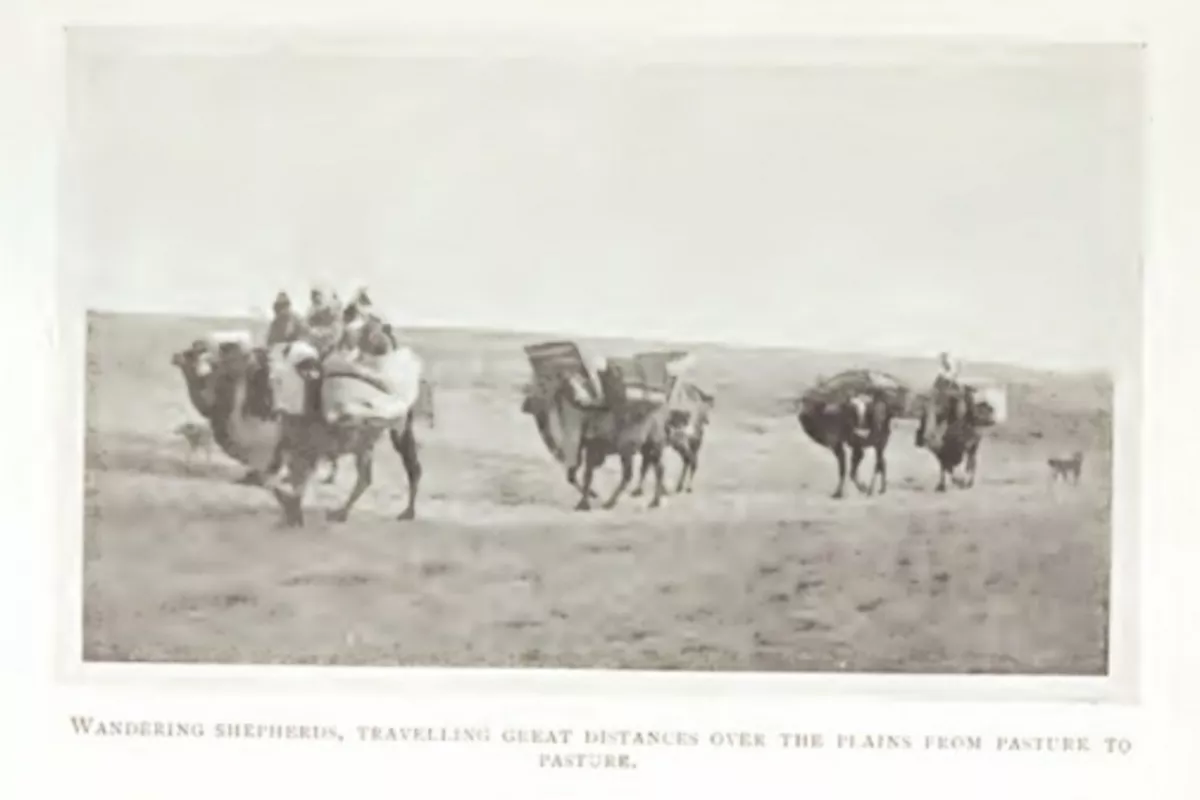

As the train carried him across Turkestan, Fox was struck by the sights outside his window: “For the first time I see, through the train windows, the round black tents of the nomads, shaped like broad beehives, and I whisper to myself that under just such a tent was Chingiz Khan born… Sometimes there passes a family on the march, the elders and children perched above their household goods on the beautiful shaggy Bactrian camels, the youths on horseback, small, sturdy ponies. It is all strange to me and I feel a beauty of slowness and order in their movements, the eternal rhythm of a wandering shepherd’s life.”

Fox shortly visited a nomadic camp, recording his impressions in the sub-section “The Tents of the Kazakhs”.

“We sat on some empty crates and watched the hens scutter across the floor,” he wrote, “while his wife, a quiet, kindly woman, brought us a bowl of Kummis (Mare’s milk) to drink.”

The hospitality of the Kazakhs left a lasting impression: “ They roused me when the meal was ready. ‘The Kazaks, men and women, sat round the pot in the dim tent, for smoke filled all the upper part now, and the sun had set. Brown arms were thrust into the mess, or painted wooden spoons, while we dainty whites were given wooden bowls. ‘The meat was tough and greasy, and to me only the little cakes of dough were palatable, though they were gritty with sand, so I did not eat much… It was all fantastic around that evil-smelling fire.”

The next day, Fox encountered a group of Lesser Horde Kazakhs migrating from Siberia along the Syr Darya River. He noted that some had already settled in Torgai, while others aimed to reach the Urals. “ Once there, they would willingly sell off their surplus stock to buy their necessities on the bazaars to last them through the following year, at Kazalinsk, at Jussali, at Perovsk and ‘Turkestan, the great bazaars of the Syr Daria.”

Fox also explored the broader historical and cultural context of the Kazakhs, noting that their nomadic lifestyle limited the development of written literature but fostered rich oral traditions and epic poetry: “It is hard to unravel their history from songs and legends, and the very nature of their nomadic life has perforce prevented the making of more certain records.”

Perhaps most striking is Fox’s clarity in using the correct national name instead of the commonly misused “Kirghiz Kazak,” a misnomer often repeated by Western writers of the time. Fox explicitly states that the “Kirghiz Kazaks have no connection with them and no right at all to the name Kirghiz. Nor do they themselves use it, but speak of their nation as Kazaks only, and so they are known by all the peoples of Asia.”

This detail is highly significant. At the time of Fox’s writing, the name “Kazakh” had only recently been officially restored in 1923, replacing years of historical misnaming. That Fox recognized this signals his careful attention to facts and respect for cultural identity.

Fox also wrote about Kazakh customs, including the baibishe-tokal (senior and junior wives) tradition, the people’s devotion to Islam, and the impact of Bolshevik policies on traditional life. His reflections end with a haunting question: “So for months we knew and loved the people… What will become of them and their steppe? Are they doomed to a sordid extinction like the [natives] of America? Or does the future still hold for them some fate not altogether unworthy of their past?”

Fox’s century-old observations remain a valuable window into the life, culture, and historical self-awareness of the Kazakh people. In our modern age, as we reclaim and re-examine our past, his account deserves renewed attention.

Share on social media