February 26 marks the 30th anniversary of the horrific Khojaly Massacre. In 1992, Armenian forces attacked the Azerbaijani town of Khojaly, brutally ending the lives of 613 people.

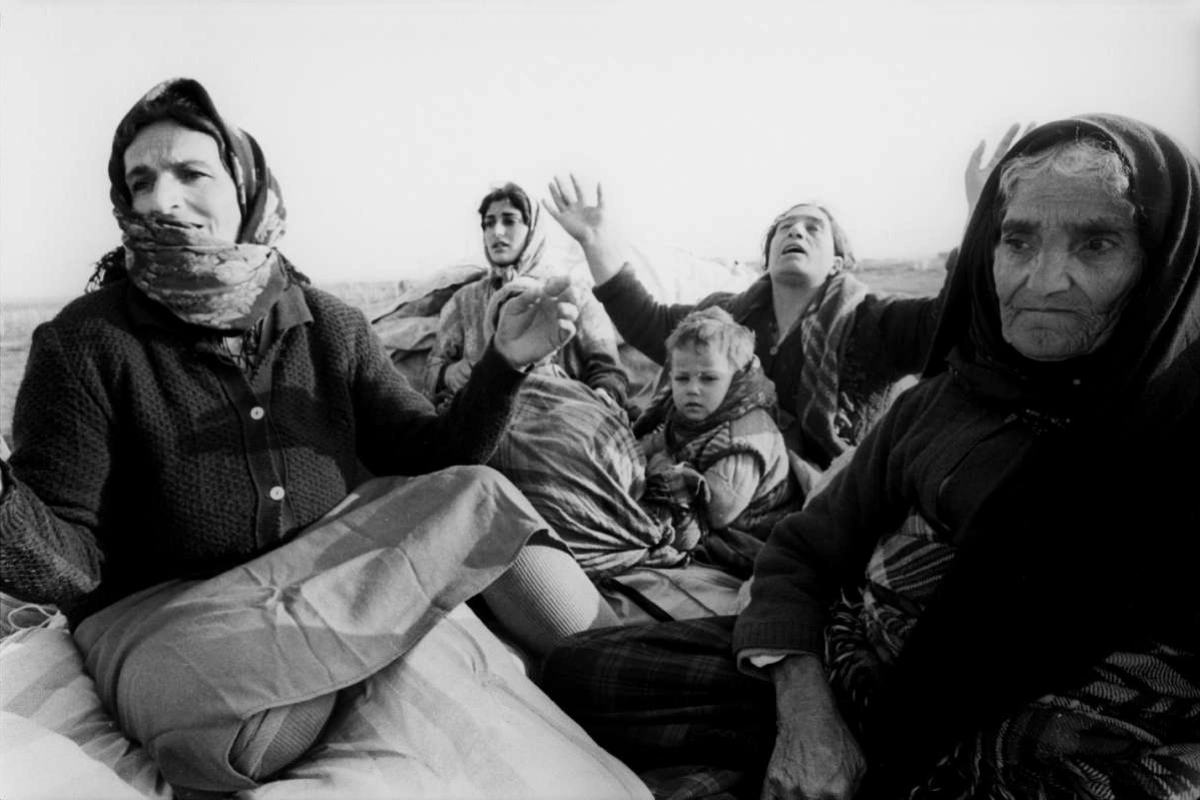

Many scenes were captured on film of desperate Khojaly survivors and of the massacre victims’ mutilated corpses - evidence that caused shockwaves in Baku and beyond. Image: Wikimedia Commons

It was the single worst atrocity of the First Karabakh War: the massacre of over 600 Azerbaijanis in the early morning of February 26, 1992. Almost all of these were civilians fleeing the small town of Khojaly, which had come under sustained attack from Armenian forces. Thirty years later, memory of the event remains an emotional lightning rod for Azerbaijanis worldwide. Monuments and an annual series of international events ensure that Khojaly is not forgotten. Though it was just one of many horrific chapters on both sides of a nasty conflict, Khojaly remains a particularly vivid symbol of the nation’s suffering.

Geopolitically, the Second Karabakh War of October-November 2020 has recast Azerbaijan from victim to victor. Some might say that this reduces the significance of the Khojaly Massacre – would it not be to Azerbaijan’s advantage to start downplaying such events to smooth relations with Armenia in the hopes of normalizing relations? The answer is no for two key reasons.

First, on a purely human level, the event is not just history but a lived experience for many and a life-changing reality for the relatives of those who died. For them, it is personally important not to de-value the memories, however painful.

The second reason is more subtle. On a geopolitical level, a ‘battle of sympathies’ is being played out on the international stage between the antagonists in the long-running Azerbaijan-Armenia saga. The Armenian people endured a huge and undeniable history of suffering with the mass deportations and massacres of 1915. Armenians receive a high level of compassion from almost all outside observers for such horrors, which are kept in the public imagination by a large, vocal diaspora. From the 1990s, however, this deep sympathy was tempered by the fact that Armenians had themselves occupied large swathes of Azerbaijani lands, defying UN Security Council rulings and all internationally accepted norms. After 1994, Armenia rejected any solution to the ‘frozen’ conflict that involved returning such territorial gains. This gave Azerbaijan a real sense of victimhood – the appearance of a plucky underdog dealing with a constantly weeping geopolitical sore.

The exact number of those who died in the massacre is disputed, but Azerbaijani sources generally put the figure at 613 including 63 children. Image: Ruad/Shutterstock

The country’s comprehensive victory in the Second Karabakh War, however, removed this more pronounced sense of grievance. In this light, it is understandable that Azerbaijanis feel a strong need to remind the world of the Khojaly atrocity. Indeed, the members of the Network of Azerbaijani Canadians, a grassroot advocacy organization of Azerbaijani community in Canada recently launched.

The Azerbaijani town of Khojaly was the site of the only airfield in the Nagorno Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (NKAO), an Armenian-administered but ethnically mixed region of Soviet Azerbaijan. It was thus a very strategic site during the brewing conflict of the early 1990s. Khojaly lies less than 10km northeast of the region’s central city, Khankendi (known as Stepanakert in Armenian), a city which had – by 1991 – ejected its ethnic Azerbaijani community as part of a wider ongoing process. By then, onlookers had already seen Armenians flee other parts of Azerbaijan and Azerbaijanis flee Armenia due to interethnic conflict. In October 1991, Armenians cut the main road linking Khojaly via Agdam to the rest of Azerbaijan. That left overloaded helicopter hops as the only way in and out of town for those sensibly afraid of passing through hostile Armenian checkpoints. As it was, helicopters were themselves frequently shot at, making the journey perilous – as described very vividly by American journalist Thomas Goltz in his Azerbaijan Diary.

In the aftermath of the massacre, journalist Thomas Goltz dashed to Agdam where he encountered “ten, then twenty then hundreds of screaming, wailing residents of Xodjali [ie Khojaly].” Image: Wikimedia Commons

It was clear to Goltz from his own visit in January 1992 that Khojaly was woefully lacking in defenders and that Baku was making no apparent attempts to reinforce the encircled town. The last helicopter flew out on February 13, leaving an estimated 3000 Azerbaijanis in Khojaly. They were without heating or electricity to deal with the cold and had barely 160 lightly armed militia-men to prevent what now seemed an inevitable Armenian attack.

The attack came on the night of February 25, as armoured vehicles from the Soviet 366th Regiment supporting the Armenian attack surrounded the town. According to two reliable witnesses from that same regiment,[1] the attack sealed off three sides of Khojaly but left an ‘escape route’ for the population to flee east through snowy forests towards Agdam. However, as dawn broke, many of the fleeing inhabitants found themselves under a hail of gunfire as they emerged onto open ground near the village of Nakhchevanik. The Azerbaijani militiamen who returned fire were swiftly killed, but the carnage of unarmed civilians continued. Evidence suggests that many people were shot at close range, and bodies were found mutilated. Some survived and were taken hostage. Others avoided what Goltz called the “turkey shoot” only to get lost in the forests and die of hypothermia. The exact number of those who died is still disputed, though Azerbaijani sources generally agree to a total of 613. A document from the Azerbaijan Presidential Library gives 503 names of Khojaly residents who perished, including 63 children, but suggests that this misses around 100 more who had not been registered locally. Some of these had recently fled from Khankendi, and others were Ahiska (Meskheti Turks) who had recently been resettled, having fled a previous pogrom in Uzbekistan.

New of the massacre led rapidly to a loss of confidence in the Azerbaijani government, then led by Ayaz Mutallibov. Why, people asked, had so little been done to ensure the defence of Khojaly when the signs of a brewing Armenian attack had been evident for months in advance? The government’s Soviet-style attempts to deny or downplay the disaster were foiled by

The massacre also caused a massive sense of insecurity for other Azerbaijani communities in Karabakh. This, in turn, led to the rapid evacuation of large swathes of the region as it became increasingly threatened by Armenian military advances over the months that followed. The importance of Khojaly in facilitating the ethnic cleansing of Azerbaijanis from the region was not lost on Serzh Sarkisian, who would become President of Armenia. In a remarkably frank interview in 2000, he told researcher Tom de Waal that it was only after Khojaly that Azerbaijanis realized their Armenian foes were not joking with them and would be prepared to “raise their hand against the civilian population.”

Although there were many appalling chapters to the First Karabakh War, Khojaly would prove the conflict’s single worst atrocity in terms of both numbers killed and psychological significance.

There are now memorials to the Khojaly massacre in many countries beyond the Caucasus. This one is in The Hague, Netherlands. Image: Wikimedia Commons

Khojaly has many sad parallels. Perhaps the most obvious is that of the Srebrenica massacre three years later during the civil wars in Yugoslavia. Like Srebrenica, Khojaly is justifiably remembered, but many, many other atrocities on all sides are largely forgotten, to the chagrin of those whose loved ones were victims. The massacre at Khojaly, like that at Srebrenica, needs to be remembered and its victims commemorated. Still, the many deaths, horrors and forced population movements that happened on both sides in the same conflicts should also be recognized to allow a more general chance for remembrance and reconciliation. Only then can communities hope to heal the wounds and start to rebuild the bonds of trust and friendship required to foster true peace.

Meanwhile, we should perhaps listen to the words of Yasemin, one of the Khojaly survivors interviewed by Ian Peart. As

[1] The Soviet army was multi-ethnic but the two deserters were from Turkmenistan and reported having been beaten by their peers for being Muslims. Ironically they fled to Khojaly where they became witnesses to the attack, and survivors of the danger-filled exodus.

Share on social media