Photo: The Kabul Times

When the Taliban returned to power in Kabul in August 2021, many observers predicted that Central Asia would soon be overwhelmed by instability radiating northward. Those predictions did not fully materialize. The region did not descend into immediate chaos, nor did it experience a dramatic surge in cross-border insurgency. Instead, Central Asia entered a more complex and arguably more difficult phase: a prolonged security dilemma defined by uncertainty rather than collapse.

This dilemma is shaped by three interlocking forces. First, Afghanistan’s transformation altered-rather than created-security risks along Central Asia’s southern frontier. Second, domestic politics across the region continue to frame “extremism” in ways that often blur genuine threats with regime preservation. Third, the regional security environment is being restructured by diverging Chinese and Russian approaches to risk management, protection, and control.

The core challenge is not that Afghanistan inevitably “exports insecurity.” Rather, Afghanistan’s instability has amplified vulnerabilities that already existed: porous borders, entrenched smuggling economies, fragile governance in peripheral regions, labor migration pressures, and information environments prone to fear-based narratives. Central Asian states are now forced to pursue three simultaneous objectives: preventing cross-border violence and illicit flows without permanently militarizing their societies; distinguishing real transnational militant threats from politically convenient extremism narratives; and navigating an increasingly competitive security marketplace dominated by Moscow and Beijing, each offering distinct-and sometimes incompatible-solutions.

Photo: TASS

Borders as Systems, Not Lines

For Central Asian states bordering Afghanistan, especially Tajikistan, the frontier is not simply a geographical demarcation. It is a multilayered system shaped by geography, society, and political economy. The Tajik-Afghan border runs through rugged terrain that is difficult to police. It also cuts across communities linked by kinship, commerce, and informal trade networks that long predate modern state boundaries. Economically, it sits atop smuggling routes that have proven resilient across decades of war, regime change, and international intervention.

In this context, border security cannot be reduced to fencing, patrols, or troop deployments. It requires the management of an entire ecosystem: surveillance and rapid-response capabilities, border livelihoods that reduce dependence on illicit trade, anti-corruption enforcement within customs and security services, and intelligence-sharing mechanisms capable of interpreting ambiguous incidents.

Recent events illustrate how volatile and politically charged this environment has become. In mid-January 2026, Tajik border guards reportedly killed four armed individuals crossing from Afghanistan. Afghan officials characterized the incident as a smuggling confrontation, while Tajik authorities framed it as counterterrorism. Such interpretive divergence is not incidental-it reflects a structural ambiguity in which nearly any border clash can be read through either a criminal or militant lens. That ambiguity, in turn, shapes policy responses, public messaging, and external engagement.

An even more consequential episode occurred in November 2025, when a drone attack launched from Afghan territory into Tajikistan killed three Chinese nationals. This incident underscored two realities often overlooked in conventional border analyses. First, spillover threats are no longer limited to small-arms infiltration; they now include technological and targeted attacks. Second, violence affecting Chinese citizens or assets instantly internationalizes local security incidents, drawing Beijing directly into Central Asia’s frontier dynamics.

Elsewhere in the region, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan have adopted a more transactional posture toward Kabul. Rather than emphasizing isolation or confrontation, they have prioritized border trade, energy exports, rail connectivity, and pragmatic engagement with Afghan authorities. This approach deliberately sidelines contentious political questions-recognition, governance, rights-in favor of what policymakers view as stabilizing cooperation. Far from naïve, this strategy reflects a calculated belief that economic interdependence can function as a form of risk management.

Yet connectivity carries its own vulnerabilities. Railways, pipelines, power lines, and logistics corridors raise the economic cost of instability, incentivizing accommodation with whoever controls Afghan territory. At the same time, they create high-value targets for criminal networks, insurgents, and transnational jihadist groups seeking to signal that no route or corridor is secure.

The resulting paradox is stark. Fully sealing borders impoverishes local communities and strengthens smuggling incentives; fully opening them invites predation. Central Asian states are therefore converging on a hybrid approach: selective hardening through checkpoints, drones, and sensors; selective openness through managed trade corridors and border markets; and the externalization of risk via security partnerships-most notably with Russia and China.

Extremism Between Threat and Narrative

Few concepts in Central Asian politics are as elastic-or as politically charged-as “extremism.” Governments across the region routinely invoke it to justify surveillance, regulate religious practice, and constrain opposition. Over time, this has produced a credibility gap. For many citizens, official warnings about extremism are interpreted as political instruments rather than security assessments. For security services, public skepticism raises fears that real dangers will be underestimated or ignored.

This credibility gap is itself a security liability. Effective counterterrorism depends on trust, cooperation, and credible threat communication. When “extremism” becomes synonymous with political control, intelligence quality deteriorates and community cooperation weakens.

Two realities must be held simultaneously. On one hand, Central Asia has experienced relatively low levels of direct terrorist violence compared with many conflict zones. On the other hand, transnational militant organizations-most notably Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISIS-K)-have demonstrated both intent and capability to operate beyond Afghanistan’s borders. These facts are not contradictory. They instead highlight the need for proportionality and precision in policy design.

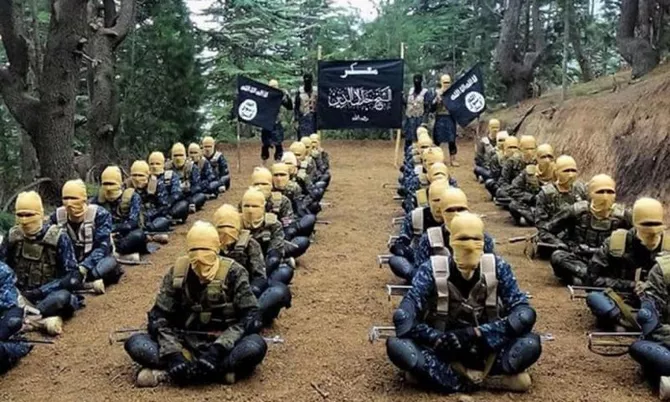

Source: ISIS-K

The Contemporary Threat Landscape

ISIS-K has emerged as one of the most aggressive and outward-facing branches of the Islamic State network. It has carried out mass-casualty attacks, plotted internationally, and deliberately targeted foreigners to maximize geopolitical impact. Its propaganda efforts have increasingly addressed multilingual audiences, including Central Asians, leveraging online platforms that bypass traditional border controls.

For Central Asia, the most acute risks do not involve large formations of fighters crossing mountain passes. Rather, they consist of interconnected threat vectors: criminal networks that overlap with militant logistics; digital radicalization pathways that transcend geography; labor migration circuits that can be exploited by recruiters; and symbolic attacks on infrastructure designed to undermine confidence in connectivity and governance.

Attacks in Afghanistan that target foreign nationals resonate beyond Afghan territory. A suicide bombing in January 2026 at a Kabul venue frequented by Chinese citizens reinforced Beijing’s perception of Afghanistan and Central Asia as a single, interlinked security space. Such incidents increase the likelihood that external powers will treat regional instability as a shared problem requiring deeper involvement.

The Consequences of Inflated Narratives

Alongside these real risks, Central Asia is often portrayed-both domestically and internationally-as inherently vulnerable to jihadist radicalization. A growing body of scholarship challenges this framing, arguing that it exaggerates threat levels and reduces complex social dynamics to a single security label. Studies have criticized longstanding “discourses of danger” that depict the region as an inevitable extremist hotspot, even when empirical evidence does not support such conclusions.

Inflated narratives tend to produce predictable policy responses: broad preventive repression instead of targeted disruption; the criminalization of nonviolent religious expression; politicized arrests that generate more noise than actionable intelligence; and increased dependence on external security patrons to address problems rooted in governance deficits.

When extremism is treated primarily as a legitimacy tool, the security dilemma deepens. Citizens disengage, communities conceal problems, and the space for lawful participation narrows. Ironically, such environments can make genuine radicalization more likely by eliminating trusted channels for expression and grievance resolution.

Photo: AP

Russia and China: Diverging Security Logics

Central Asia’s external security environment is undergoing a quiet but consequential transformation. For much of the post-Soviet period, Russia served as the region’s default hard-security provider, maintaining military bases, training forces, and anchoring collective defense arrangements. China, by contrast, emerged as the dominant economic actor while keeping its security role limited and selective.

That division of labor is eroding. Afghanistan’s instability, ISIS-K’s transnational ambitions, and attacks affecting Chinese interests have drawn Beijing into more overt security practices. At the same time, Russia’s war in Ukraine has strained Moscow’s capacity and altered regional perceptions of its reliability, even as it retains deep institutional and military ties across Central Asia.

What is emerging is not a straightforward rivalry but a competition between models.

Russia’s Security Offer: Institutions and Force Posture

Russia’s comparative advantage lies in institutionalized security cooperation. Through alliance structures, forward deployments, and interoperability frameworks, Moscow offers Central Asian states a familiar and immediately usable toolkit. Tajikistan occupies a central position in this approach, serving as a frontline state in efforts to reinforce the Afghan border.

Collective mechanisms emphasize joint exercises, shared planning, and visible deterrence. Russian narratives consistently highlight Afghanistan-linked threats to justify sustained engagement and military presence. For governments seeking rapid capacity enhancement, this model is attractive: it delivers training, equipment, and a coherent operational doctrine.

Yet the costs are significant. Deep integration with Russian systems can constrain foreign policy flexibility, entrench militarized responses to socio-economic problems, and bind states to Moscow-centric threat perceptions that may not always align with local realities.

China’s Approach: Protection Through Connectivity

China’s security engagement follows a different logic. Rather than alliance commitments, it prioritizes risk management: securing borders, protecting infrastructure, and preventing militant linkages that could affect Xinjiang. Cooperation has increasingly taken bilateral forms, complemented by multilateral counterterror frameworks emphasizing shared threats.

In practice, this translates into training programs, surveillance technologies, policing cooperation, and infrastructure protection measures. The emphasis is preventive and asset-focused, aiming to disrupt perceived risks before they materialize.

This model appeals to governments because it comes bundled with financing, investment, and connectivity projects. However, it also carries risks: the expansion of surveillance states, growing debt dependencies, and a security agenda oriented more toward protecting corridors and projects than addressing everyday citizen security.

Hedging Between Two Patrons

For Central Asian governments, the divergence between Russian and Chinese approaches presents both opportunity and danger. On the positive side, it enables hedging-drawing on Russian military capabilities while leveraging Chinese technology and investment. This supports broader efforts to diversify partnerships and enhance strategic autonomy.

On the negative side, dual patronage can fragment security doctrine. One system may prioritize alliance warfare and territorial defense, while another focuses on internal control and asset protection. In moments of crisis, competing command cultures and intelligence silos can complicate response and politicize threat interpretation.

Photo: avim.org.tr

The Core Security Dilemma

At its essence, Central Asia’s post-Afghanistan challenge can be summarized simply: the region must counter real transnational threats without allowing counter-extremism to substitute for governance, while navigating a security marketplace where Russia offers institutions and force posture and China offers technology and connectivity protection.

Toward a More Sustainable Strategy

A viable regional approach does not require choosing between Moscow and Beijing. It requires choosing principles first and then acquiring capabilities accordingly.

Border security should be treated as a governance project rather than a purely military task. Anti-corruption measures, accountable customs systems, and legal trade channels are as important as patrols and sensors. Threat assessment must be disciplined, separating crime, insurgency, and terrorism instead of collapsing them into a single label. Community trust should be recognized as a counterterror asset, not a vulnerability.

Regional early-warning mechanisms and intelligence fusion-particularly through multilateral and UN-linked formats-can help standardize assessments and reduce politicization. External partnerships should be used selectively, with domestic oversight of surveillance tools and clear legal constraints.

A New Baseline, Not a Temporary Shock

Central Asia’s post-Afghanistan environment is not a passing phase; it is a new baseline. Borders will remain contested spaces where crime, politics, and militancy intersect. Extremism will persist as both a genuine transnational risk and a tempting domestic narrative. Russia and China will continue to offer competing security logics-one rooted in alliances and force, the other in technology and connectivity.

The region’s long-term stability will depend on its ability to treat security not as a permanent emergency but as a sustained governance challenge-while remaining prepared for periodic shocks as Afghanistan’s instability and ISIS-K’s opportunism continue to test the frontier.

Share on social media