Growing up in Almaty, Leila Mekhdiyeva started to discover prejudice against her for being half-Azerbaijani. However, rather than giving up her mixed identity, she went on to explore and celebrate her Azerbaijani roots.

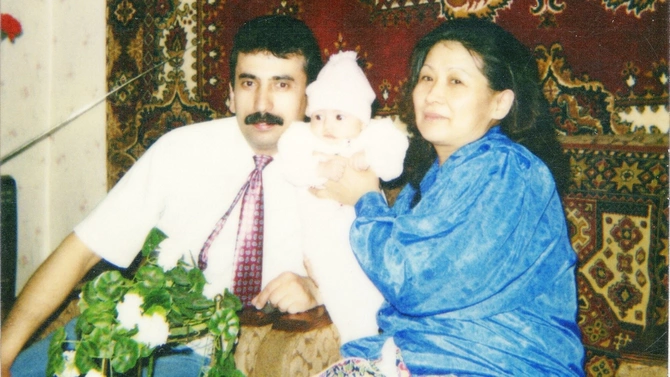

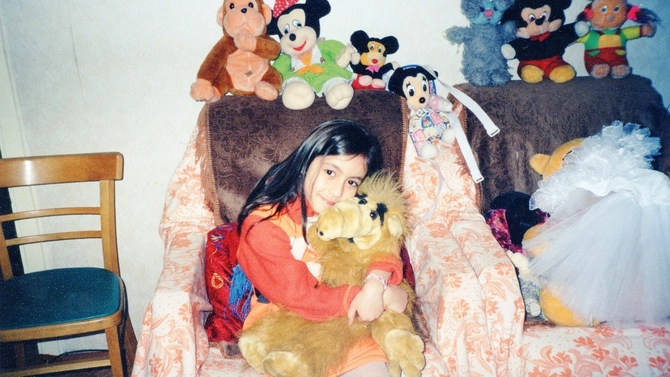

Leila Mekhdiyeva, who now lives in Prague, grew up with two cultural identities, Azerbaijani and Kazakh, in Almaty, Kazakhstan. All images provided by Leila Mekhdiyeva.

The first time I tried dolma, I was nine years old. For those who don’t know, dolma is a prominent Azerbaijani national dish – the best-known version made by wrapping meat into grape leaf parcels. The same dish is typical across much of the Middle East if sometimes named differently. Still, for Azerbaijani households, dolma is especially important – perhaps as archetypal as pasta is for Italians, paella for Spanish, or borsch for Ukrainians. And there I was, a nine-year-old kid on my first trip to my father’s motherland, eating the food of my people for the very first time.

As a mixed half-Azerbaijani and half-Kazakh child born and raised in Almaty, Kazakhstan, in a Russian-speaking family, I’ve had identity issues my whole life.

My Azerbaijani father moved to Almaty at 20, right after serving in the Soviet Army. Like many other Azerbaijanis at that time, he had left his small village in Mingachevir, Azerbaijan, hoping to find a better life. Living under Soviet rule[1] was far from ideal for most Azerbaijanis.

Back then, Azerbaijani immigrants to Kazakhstan and other Soviet Republics were mostly poorly educated people escaping poverty and a lack of opportunities to make a living – and enough extra money to be able to help their families back home.

Without proper education, connections, and knowledge of Russian, the prospects weren’t that promising. Typically most found themselves taking low-income jobs — from selling fruits and vegetables at the bazaars to making shashlik (shish kebab – barbequed skewers of meat) in simple cafes. This created the Soviet-era stereotype of Azerbaijanis as uncultured folk unable to succeed in any intellectual job. They were subconsciously grouped with other diasporas from the Caucasus as “wild barbarians.” The notion was shared across the USSR, not just in Kazakhstan.

Of course, this stereotype was far from true for many Azerbaijanis, and my father’s path was rather different. He worked for four years as a fitter in an Almaty cotton mill before going to the police academy. When the Soviet Union collapsed, he was working as a policeman. He was granted Kazakhstani citizenship, and with that, his connection to Azerbaijan ended. At least on paper.

In reality, I grew up seeing my father longing for his native home, keeping up with a small circle of Azerbaijanis in Almaty. I remember he often drove us to a small Azeri-owned bakery when I was a child, where they made tandir chorek. I remember seeing how excited my father was to share fragments of his national cuisine with me. Now I realize that he was, in some deeper sense, sharing a bit of himself.

From a very young age, I was aware of my ethnicity. I don’t know if it’s common for other diaspora kids, but I believe it was my father’s way of making me aware of my roots and not losing my identity. Or rather, making sure I didn’t lose his.

Many diaspora children probably grew up hearing the same stories of our parents’ tough lives back home. I certainly did. My father would tell me how he and his siblings were sleeping in the same room with their mother while his father – my granddad – had a room for himself because his health had been deteriorating since coming back home from World War II. Many times there would be no prepared food for my father when he came home from school, so he would take a few sugar cubes with bread and sit on a tree stump, passing the time before doing his homework. He told me he loved studying, his favourite classes being geography and history, and growing up, he wanted to become a historian, but there was never time to study formally. He needed all his energy to survive in a distant republic. Yet despite all the hardships he had been through, he never stopped missing his motherland.

I don’t remember when exactly I started feeling ashamed of being Azerbaijani. Was it when I realized that no one around looked like me?

Was it when my father would not allow me to wear short skirts, paint my nails, sport temporary tattoos or have highlights in my hair (all things that I saw my non-Azerbaijanii friends do)?

Or was it perhaps when I saw older Azerbaijani women who had chosen a very traditional path of “wife and mother” and asked myself, “is that all there is for me when I grow up”?

Instead of being raised aware of our traditions, food, celebrations, history, and culture, I was made to feel that being Azerbaijani, specifically a girl, comes with endless rules and prohibitions. In my childhood brain, the only way to avoid endless limitations and traditionalism was to deny my “Azeriness.” I did that for years. I was proud to say that Russian was my native language. I would cringe at my father listening to Azerbaijani songs in our car. I would conspicuously put on my headphones and drown out the noise with loud American music and ask him to turn off his music because it was embarrassing.

In the 1990s and 2000s, racism towards Caucasians in post-Soviet countries was at its peak. There were attacks on Caucasians in Russia by skinheads, offensive jokes on TV mocking Caucasians and portraying us as lowbrow nations, and such racist and derogatory terms as “hach” and “blackasses” were widely used towards Caucasians. People in post-Soviet countries could see no difference between, for example, Azerbaijanis and Chechen or Dagestani and Georgian, so the hurtful stereotypes used to define all of us were interchangeable.

One day something in me switched. At some point during my teenage years, I became more curious about my ethnic background, history, culture, and what it meant to be Azerbaijani. It was as if, by finding an answer to that question, I could maybe find where in the world I belonged. As any other millennial teenager, I turned to my best friend, the World Wide Web.

I’d like to pretend that I learned all about the Safavid Empire and other great facts about Azerbaijan’s history that made me proud to be Azerbaijani. That would make this story truly inspiring, but unfortunately, it was not the case. I didn’t learn much about my people and our history until later. What really influenced an awakening in me was learning about Khojaly, the 1992 massacre of over 600 Azerbaijanis by Armenian separatist militia abetted by troops of the 366th CIS regiment. Although I hadn’t been aware of many things connected to my Azerbaijani background, I did know about Karabakh - mostly because of my father. In 1989, when he was studying in the police academy, he was sent to Karabakh to ensure security during the ethnic conflict between the Azerbaijanis and Armenians of Karabakh. Although I hadn’t even been born at the time, I saw the occupation of Karabakh through my father’s eyes my whole life. What I didn’t know up to that point was to what extent there was such deep hatred toward Azerbaijanis.

The first time I saw photos from that night, I couldn’t stop crying. Learning that the world did nothing when that happened to my people was devastating. All the more so when those responsible for the crimes continued to live unpunished in the areas of Karabakh they had occupied.

As I started to embrace my Azerbaijani origin, I simultaneously started noticing more politically incorrect and sometimes even racist comments regarding “my people” when I was still living in Kazakhstan. There were comments about how lucky I was that my father was sending me to study in Europe, because usually “my people” just marry their daughters off as soon as they turn 18. Some pressured me, saying to succeed in Kazakhstan, I should claim to be an ethnic Kazakh to “open more doors.” And once, during my senior year in high school, I was arguing with my classmate when out of the blue, she told me to “go back to my country.” That day I had been wearing my “I heart Azerbaijan” t-shirt, purchased during a previous trip to Baku. Although I was half-Kazakh, born and raised in Kazakhstan, it seemed like I would never stop facing racist remarks and discrimination. It was no surprise that I decided to leave Kazakhstan after high school.

After I moved to Europe, I met many Azerbaijanis from the Republic. These were not the impoverished Azerbaijani immigrants of my father’s generation. Instead, they were primarily middle-class kids who’d moved to Western countries to study. They were often fluent in three or four languages. They didn’t have to support their families back home, and there were a lot of different career paths for them to choose from. All this has given me hope that the next generation of Azerbaijani immigrants’ children will have an even stronger diaspora with growing opportunities to learn our own culture, history and language.

I started this story by mentioning my first time eating dolma at the age of nine. Since then, I have learned to make dovga, qutab, and pakhlava — although I never made dolma (I’m a vegetarian). I have found so many Azerbaijani songs that I enjoy — although my father and I still have very different tastes when it comes to music. I have a few friends from Azerbaijan with whom I try to practice my Azerbaijani language — although it’s still far from perfect. Today, for me, being Azerbaijani is more than the length of my skirt, my ability to speak the language or to cook dolma. Being Azerbaijani is loving and embracing my roots, and representing my people in every room I enter. Being Azerbaijani means passing to my children this love and feeling of belonging. I no longer let anyone define for me what it means to be Azerbaijani, or what I can and cannot do. It is nobody’s business but my own.

There is a part of me that envies my Azerbaijani friends who grew up surrounded by people who look like them, not feeling judged by others and never questioning their sense of belonging. Sometimes, I wonder how different my life would be if I weren’t a diaspora kid. I also recognize the importance of being a model for other diaspora kids who might feel lost, confused, and lonely, those who will need help creating their identity and not forgetting their origins. If we don’t teach them Azerbaijan’s history or educate them about the richness of our culture and traditions, we leave it for others to define what it means to be Azerbaijani. Instead of being angry or ashamed when others make dishonest stereotypes and offensive portrayals of us, we must create a place where all diaspora kids can learn more about themselves and their origins. With more mixed marriages and more people leaving Azerbaijan due to globalization, it’s an important aspect to bear in mind as younger Azerbaijanis become more progressive.

[1] Or, as I see it, ‘occupation.’

Share on social media