Kazakhstan’s President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev has publicly stated that he favors an international consortium with participation by comreipanies from China, France, Russia, and South Korea. This option, however, faces logistical challenges, particularly in dividing responsibilities among consortium members and determining the sourcing of critical components.

Image: TCA, Aleksandr Potolitsyn

There are three generally discussed possibilities for construction of Kazakhstan’s newly approved nuclear power plant (NPP). One is that Russia is sole contractor. Another is that China is sole contractor. Each of these choices has its own rationale yet also geo-economic and geopolitical drawbacks for Kazakhstan. Third, Kazakhstan’s President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev has publicly stated that he favors an international consortium with participation by comreipanies from China, France, Russia, and South Korea. This option, however, faces logistical challenges, particularly in dividing responsibilities among consortium members and determining the sourcing of critical components, The Caspian Post reports citing foreign media.

Tokayev has already discussed with France’s President Emmanuel Macron the possible participation of the French companies Orano and EDF in particular. Orano focuses on various aspects of the nuclear fuel cycle, including uranium mining, enrichment, and waste management. EDF specializes in design, construction, and operational management.

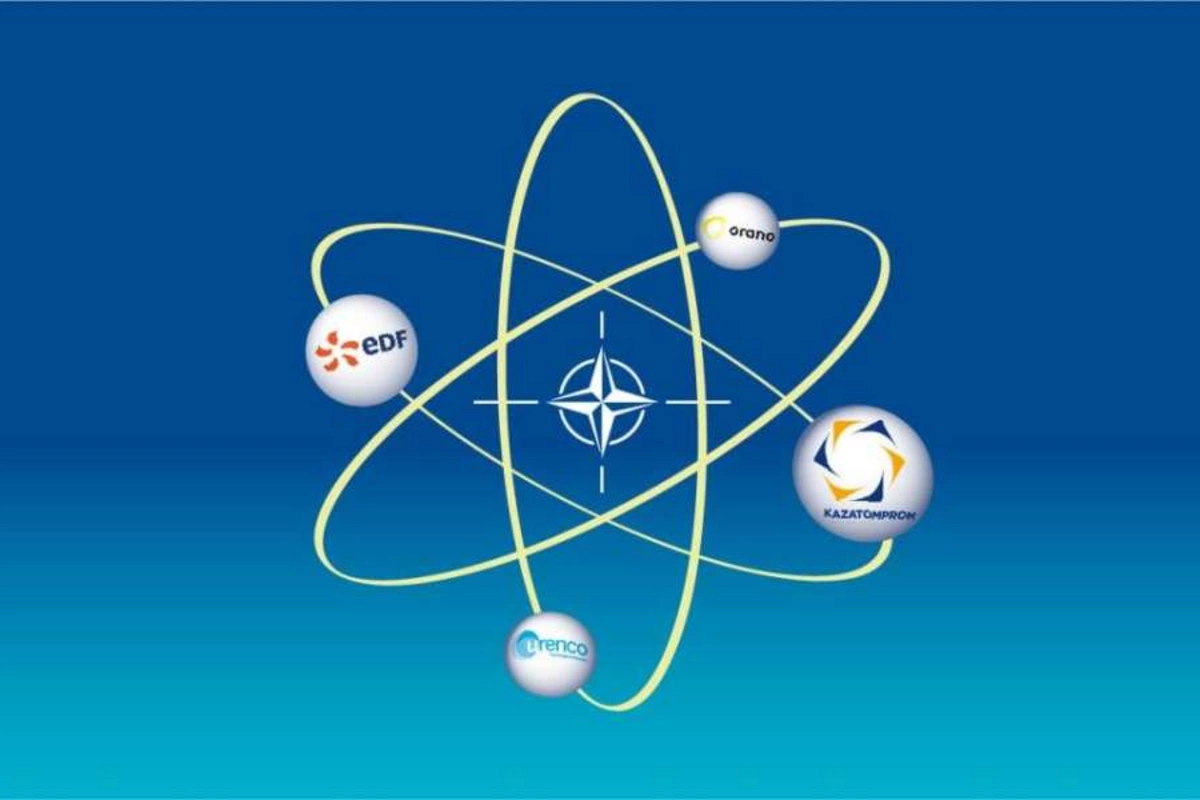

This opens the door to a fourth possibility. Orano, EDF and the British-German firm Urenco together can provide all the NPP construction and management services necessary to realize the project. But Kazatomprom, which focuses on mainly on mining and processing, has not been mentioned in any of these schemes.

Such an alternative approach, involving Western companies like Orano, EDF, and Urenco, could ensure comprehensive services with strong Western involvement, possibly including Kazatomprom, thus boosting local capacity and creating a “demonstration project” for broader natural resource collaboration within NATO frameworks. This kind of partnership could help Kazakhstan reduce its dependency on single external actors, thereby enhancing its strategic autonomy. Moreover, by involving Kazatomprom, the project could focus on knowledge transfer and capacity building, fostering local expertise and reducing external dependencies over time.

It is reasonable that an offer to take Kazatomprom into a Western consortium and to make capacity building in Kazakhstan, at Kazatomprom and elsewhere, an explicit goal of the project, would be welcome in Astana. Cooperation via NATO platforms could likewise offer Kazakhstan access not only to technical specialists from NATO countries but also to more joint training exercises and workshops, to complement an exchange of knowledge on best practices in nuclear safety and energy resilience.

And that would be only a “demonstration project” for the constructive expansion of the energy component of NATO’s Partnership for Peace (PfP) into broader natural-resource and rare-earth domains. Indeed, there is no reason even to wait for the NPP project. Central Asia, especially Kazakhstan, is a periodic table of the elements, especially rare-earth elements, and their exploration and development has been under way for some time.

Building upon the energy-security successes through NATO’s PfP, this proposal suggests expanding cooperation with Caspian region Partner countries into the mining sector, specifically for rare-earth elements critical to defense. Extending PfP to include these resources aligns with NATO’s and Partners’ core security goals, offering broader opportunities to secure the supply chain and enhance collective defense capabilities. This extension also presents a strategic avenue to mitigate risks associated with supply disruptions and geopolitical tensions.

Leveraging the extensive experience of partnership in energy security, NATO and its Partner countries could begin with joint feasibility studies on integrating mining supply chains within the PfP framework, focusing on Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan’s production and transport capacities for strategic minerals. This would start with technical workshops and readiness assessments for pilot projects, potentially leading to robust collaborations. These feasibility studies would consider both economic viability and the political landscape, aiming to create sustainable pathways for resource development.

For NATO countries, securing access to rare-earth resources is crucial for the production of advanced defense technologies, which underpin military readiness and technological superiority. Meanwhile, Partner countries could benefit significantly from improved management and security of their mining operations, enhancing both autonomy and economic development, while also reducing potential vulnerabilities that external actors might exploit.

The mining sector’s inclusion in PfP would also support regional stability by reducing dependence on single-source suppliers and mitigating geopolitical risks. Such diversification is vital in a region where overreliance on specific actors has historically increased susceptibility to coercion and economic instability. NATO’s support would not only help Partners develop their resources but also enhance their defense capabilities, ultimately securing vital supply chains that are integral to both military and economic resilience.

A principal initiative involves extending NATO’s Critical Energy Infrastructure Protection (CEIP) programs to mining infrastructure for rare-earth elements. The CEIP framework can facilitate NATO member states’ technical support for securing these infrastructures along the Middle Corridor, including the establishment of task forces dedicated to safeguarding critical infrastructure. These task forces would have a multifaceted role, from conducting risk assessments to creating response protocols that can be employed during times of increased geopolitical tension. Through collaboration, these efforts would bolster the physical security of mining sites and transport routes, ensuring that critical materials can be extracted and distributed without significant disruptions.

Three subsidiary initiatives could be pursued to strengthen this strategy: improving governance and transparency, aligning regulations, and encouraging investment. The first initiative would use NATO’s Building Integrity (BI) program to enhance transparency in mining contracts, minimizing risks of corruption and mismanagement, which can threaten both economic stability and security. Transparency efforts would ensure that exports of rare-earth elements for military applications are not compromised by inefficiencies or corrupt practices.

The second subsidiary initiative involves harmonizing regulations between NATO member states and Central Asian countries, fostering a cooperative resource management approach and ensuring smooth export processes for rare-earth elements. Regulatory harmonization would also help establish standardized procedures for safety, environmental concerns, and compliance, creating a predictable and conducive environment for long-term cooperation.

The third initiative would aim to encourage member states to invest in Central Asia’s extractive industries via public-private partnerships (PPPs), promoting joint ventures focused on technological advancements and sustainable mining techniques. Such partnerships could introduce cutting-edge extraction and refining technologies, improving yields and reducing environmental impacts, which are often key concerns for local populations and governments.

The partnership’s benefits are mutual: technological cooperation in mining would bolster regional economic growth while simultaneously meeting strategic security goals. NATO platforms could play a crucial role in promoting these efforts, ensuring secure supply chains by leveraging CEIP’s technical expertise. By enhancing regional mining operations through NATO’s existing mechanisms, these initiatives would provide a more diversified supply of critical minerals, benefiting all stakeholders.

Azerbaijan, with its well-established experience in balancing energy export routes and managing complex international relations, could facilitate regional partnerships in mining between Kazakhstan and other Central Asian nations. This aligns with Azerbaijan’s growing strategic role and would support broader diversification efforts, particularly through the development of infrastructure like the Port of Alat.

By building on existing relationships, Azerbaijan could act as a mediator and coordinator, helping align the interests of various Central Asian countries while ensuring that all parties benefit. Azerbaijan could also help mediate agreements, benefiting all parties involved and promoting regional stability.

However, a prompt start is crucial to seize these opportunities. China has recently joined the Middle Corridor and made significant inroads, such as purchasing half of Kazakhstan’s annual uranium ore production, indicating an acceleration in regional dynamics that could undermine NATO’s strategic interests. The Middle Corridor, which has increasingly become an axis of logistical and economic activity, stands at a crossroads between Western and Chinese interests.

The emerging bifurcation of the international system into an Anglosphere and a Sinosphere will likely deepen over the coming years, setting the framework for future international interactions. The decisions taken now will be pivotal in determining whether the region will prosper with a balance of power or become dominated by external pressures from more assertive actors. Engaging now, with a proactive and comprehensive strategy, will help set the groundwork for a resilient regional structure that benefits from diversified support, thereby resisting potential monopolistic influences.

Things are moving rapidly in Central Asia, and decisions made in the next few years will shape the trajectory of the region for decades to come. The structural bifurcation of the international system, marked by an intensifying divide between the Anglosphere and the Sinosphere, calls for prompt action. The development and control of critical infrastructure and resource supply chains in Central Asia will play a defining role in this emerging order, making the timing of NATO’s involvement crucial. By building these frameworks today, NATO and its Partners can ensure a stable, prosperous future that supports not only regional players but also the security and strategic needs of the broader international community.

Share on social media