Photo: themuslimkit.com

It so happened that all great poets, musicians, and artists belonged not only to the nation whose roots had nourished them, but also to the entire world. By changing and transforming it, they became a kind of bridge that often linked civilizations and cultures that were polar opposites.

The great poet Nasimi, having outpaced his contemporaries by several centuries and having mastered the finest traditions of Eastern literature, created a fundamentally new kind of poetry. In it, with the passion characteristic of poets, he championed the power of the human spirit and the power of consciousness, equating human capabilities with the divine. For this, he was persecuted all his life and ultimately subjected to a horrifying execution in Syria (Aleppo).

Nevertheless, this article is not only about him, but also about many other outstanding sons of the Azerbaijani people who, by force of circumstance, found their final resting place in foreign lands.

In the Middle Ages, the East formed a single community, reminiscent in some ways of today’s European Union, where poets, scholars, artists, and people of the arts could freely travel, exchange experience with colleagues from other countries without any visas, and discover the world through the prism of another culture. In those days, the languages of communication were Arabic, Azerbaijani, and Persian. Europe, slumbering at the time under the yoke of the Inquisition’s obscurantism, knew not even a fraction of the splendor and luxury that reigned in the palaces of sultans, caliphs, and shahs. Calligraphy, poetry, architecture, astronomy, mathematics, and medicine in the East of that period reached an extraordinary level of development. An era of rebirth had dawned-a veritable Renaissance. Yet the fate of its architects was far from easy.

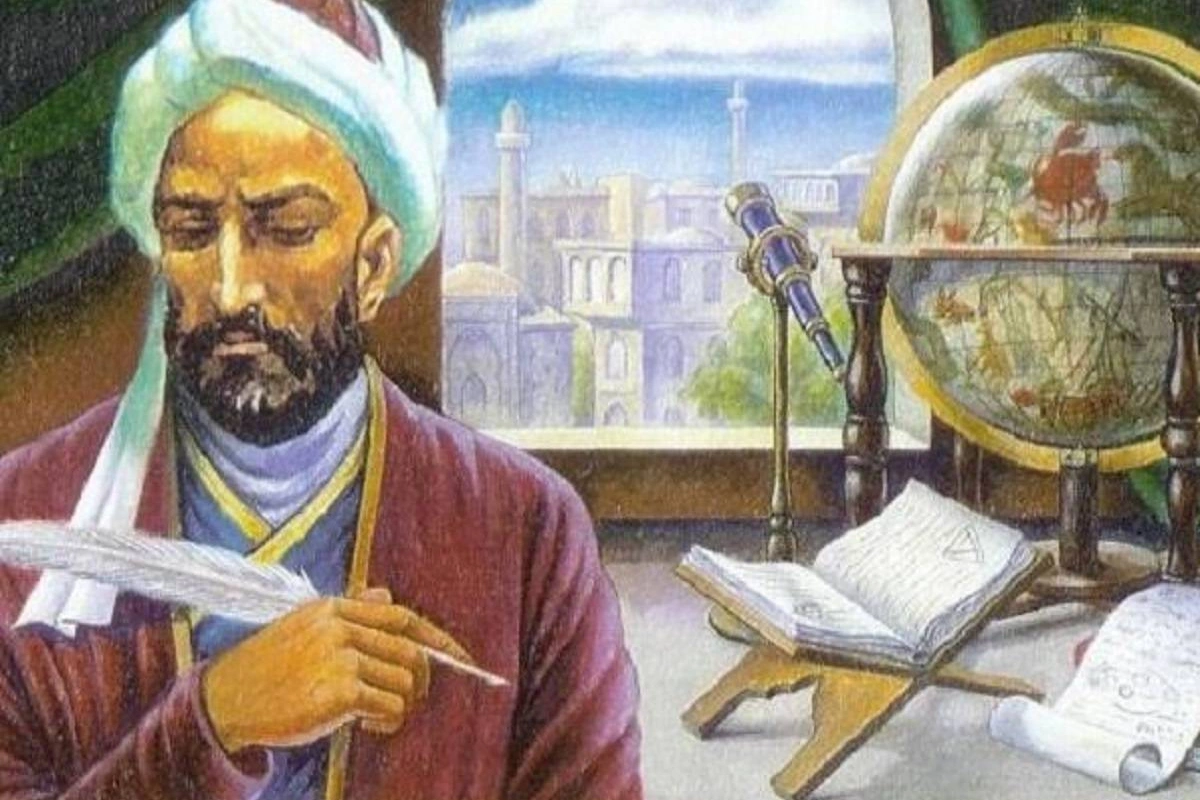

One could say that the most fortunate of them was the great scholar and astronomer Nasir al-Din Tusi. Born in 1201 in the city of Hamadan, like many scholars of his time, he was a polymath. He authored more than a hundred substantial scientific works on astronomy, mathematics, medicine, philosophy, and ethics. Incidentally, most modern researchers believe that he was first and foremost a mathematician. His works played a major role in the development of modern geometry and trigonometry. Likewise, his scientific treatises on history, medicine, music, economics, and geography are widely known. Tusi’s manuscripts are scattered all over the world-in Oxford, Leipzig, Munich, Paris, Cairo, Istanbul, Moscow, St. Petersburg, and Kazan. Despite his fame, this great scholar fully experienced the wrath of the powerful of his day. For his work, Akhlaq Nasiri-which brought him worldwide renown and was translated into many languages-the ruler of Kuhistan, Nasreddin, considered the book highly offensive and ordered Tusi’s arrest, imprisoning him in the impregnable mountain fortress of Alamut (“Eagle’s Nest”).

Tusi lived in that fortress, in exile, for over twenty years, under incredibly difficult conditions yet never ceasing his scientific endeavors. There he produced an entire series of scholarly works. In 1253, Hulagu Khan-the grandson of Genghis Khan-embarked on a campaign to the Near East. His troops captured the fortress, freed the prisoners, and Tusi was appointed as the Khan’s personal advisor.

Artistic depiction of Nasir al-Din Tusi by Najafgulu Ismailov, medieval scientific manuscripts, and choghur. Museum of the History of Azerbaijan, Baku. (Wikipedia)

Over time, the scholar’s authority grew so great that he often had to assume responsibility for major political decisions. Hulagu Khan, for instance, hesitated for a long time before storming Baghdad-Islam’s holy city-yet Tusi’s scientific arguments convinced him to take that step, which ended the five-centuries-long Abbasid rule. After conquering Baghdad, Hulagu Khan made Azerbaijan the center of his vast empire, initially making Maragha its capital and then later moving it to Tabriz. During that period, Tusi realized his dream of building an observatory in Maragha. The story of how it was constructed is quite fascinating. When Nasreddin Tusi presented the estimated costs to the ruler, Hulagu Khan questioned the feasibility of the observatory because of the staggering sum. To illustrate the importance of his project, Tusi suggested rolling an empty washbasin down a steep mountain without warning anyone in advance. This was done. The basin barreled down the mountain with a tremendous clamor, causing Hulagu’s troops to panic. Tusi then remarked, “We know the cause of the noise and remain calm; the troops do not. Thus, knowing the causes of celestial phenomena, we will remain calm on earth.” These arguments convinced the descendant of Genghis Khan, and the scholar began creating the observatory.

Nasreddin Tusi personally chose the instruments, designed the building, and gathered the most capable and forward-thinking scholars from Damascus, Mosul, Tiflis, Shirvan, and China. The observatory featured a library of over 400,000 books and a school for training new scientists. The staff was international: Turks, Persians, Arabs, Tatars, Georgians, Jews, Mongols, Chinese, and others. There were more than a hundred scholars in total, and Tusi secured a stable salary for all of them. The Maragha Observatory played a critical role in the development of practical astronomy.

The great scientist died in Baghdad. His gravestone bore the inscription: “Helper of religion and the people, Shah of the land of science.”

Thus, fate and fortune, one might say, smiled upon this great scholar. Yet there are other, more tragic examples of exceptional figures of science and art from that era. One such individual is the brilliant musician and composer Safiaddin Urmavi (1216-1294), who spearheaded a revolution in musical notation of his time. By the end of his life, though, he had fallen out of favor with the ruler and spent his final days in a debtor’s prison in Baghdad. Legends circulated about him during his lifetime: on one occasion, while Urmavi was playing the oud in the garden of Baghdad’s ruler, his music attracted a nightingale that, losing all fear of humans, flew right up to him and began to sing in harmony with the music.

Legend aside, Urmavi’s achievements as a musical theorist are undisputed. He was the first in the East to formalize and refine a system of musical notation that was in use until the end of the 19th century. Letters from the Arabic numeral system denoted the pitch, while numerals indicated the duration of the note. This system was convenient because it could capture intervals smaller than a semitone. As is well known, modern Western notation cannot record intervals smaller than a semitone and thus cannot convey all the nuances of mugham or Eastern music in general. Over time, however, from the late 19th century into the early 20th century, an alternative quarter-tone system emerged in Europe, enabling the recording of quarter tones. Modern musicians still actively use this system today. Two prominent European musicologists-R. Erlanger and J. Farmer-independently succeeded in transcribing Urmavi’s works into modern notation. Thus, a melody that had fallen silent for more than seven hundred years finally came to life once again.

Another noteworthy figure is the Azerbaijani musician Abd al-Qadir Maraghi, who was born in the 14th century in the city of Maragha. He was also a talented artist, calligrapher, and poet, writing in Azerbaijani, Farsi, and Arabic. As a court musician under Sultan Husayn, Maraghi commanded significant recognition and respect. After Tamerlane’s arrival in Azerbaijan, many of the country’s leading artists were taken to Samarkand, including Maraghi. Twice he miraculously escaped execution. The first time, he was spared because he addressed the “Ruler of the Universe” in the Turkic language; the second time, Timur’s anger was assuaged by Maraghi’s masterful chanting of a sura from the Quran. He died in 1436 in Herat.

Photo: dailysabah.com

It is telling that most art was created within palaces, where an artist’s life often hung by a thread. Palace intrigues spared no one-not Khagani, who spent a long time in the shah’s dungeon, leaving behind his “Habsiyyat” cycle of prison elegies as testimony to that era, nor Habibi, who was exiled to Turkey following Sultan Selim’s conquest of Tabriz and died there. Incidentally, Khagani’s very dungeon still exists to this day, a silent witness located near Siyazan, on the grounds of the ancient settlement of Shabran.

Just as rulers’ wrath was not always just or timely, neither was their mercy. The painter Sadiq-bey Afshar, who was renowned not only in his homeland but also in Isfahan and India, served under Shah Abbas as a librarian, receiving a pittance from the state chancellery. Many of the portraits he created have survived to this day and are housed in museums in Istanbul, Paris, St. Petersburg, and Boston. Experts believe his work strongly influenced the Iranian school of miniature painting.

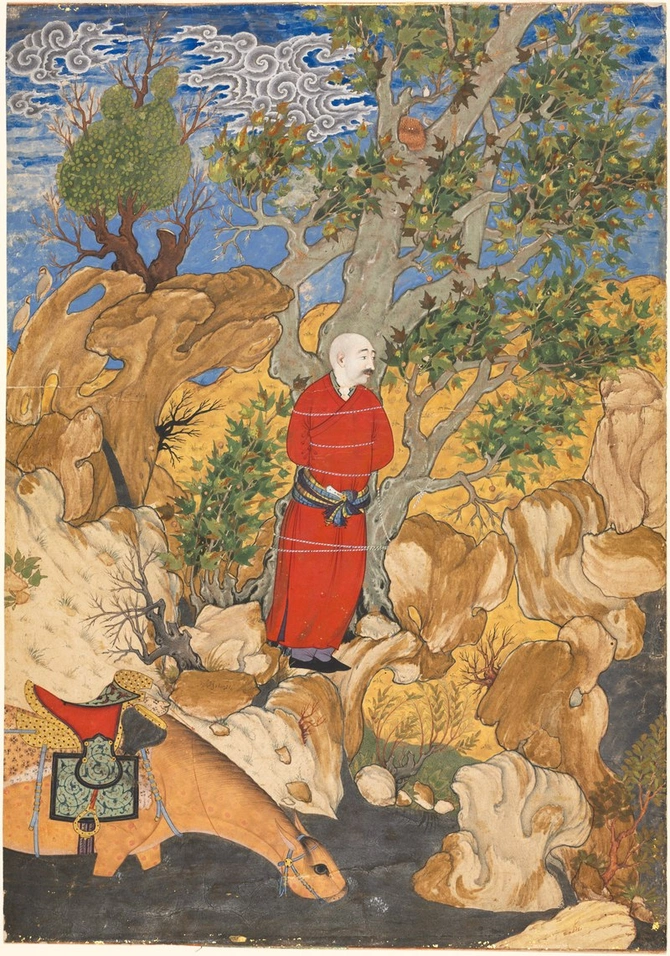

Painting by Sadiqi Bey titled Aulad Tied to a Plane Tree, from a Shahnama by Firdausi (Wikipedia)

Meanwhile, his colleague, the great artist Mir Sayyid Ali, left his homeland in anger and moved to India, where he enjoyed universal respect and fame at the Indian court. Today, the British Museum in London preserves a manuscript of Nizami’s Khamsa created for Shah Tahmasp between 1539 and 1543. It is adorned with fourteen large-format miniatures painted by the most outstanding Azerbaijani artists of the 16th century: Sultan Muhammad, Agha Mirek, Mir Musavvir, Mirza Ali, Mir Sayyid Ali, and Muzzafar Ali. One of the finest miniatures-Majnun by Layli’s Tent-was done by Mir Sayyid Ali. His works are housed in the world’s leading museums. It is widely accepted that Mir Sayyid Ali’s oeuvre and the Tabriz school he represented influenced the development of the Mughal school of miniature painting in India, just as the Tabriz artists Shah Quli Tabrizi, Veli Jan, Kemal Tabrizi, and others shaped the rise of the Turkish miniature school.

Of course, there were always masters who preferred freedom to the dangers of a comfortable life at court. Fuzuli, despite his fame and acclaim, refused to become a court poet, believing that “he could not bear the burden of gratitude to the shahs.”

Poverty dogged him his entire life, and Fuzuli ended his days in Baghdad-then considered the Eastern Rome. Perhaps the suffering one endures in life and the recognition one receives posthumously partly compensate for the injustice and imperfections of our world. But not everyone had even that small measure of luck. A prime example is the fate of the poet Mirza Shafi Vazeh. The German writer Friedrich von Bodenstedt became Mirza Shafi’s student, receiving from him a notebook of poems as a gift. Bodenstedt successfully translated these verses into German. The book’s release caused such a furor in Europe’s literary circles that Bodenstedt was overwhelmed by his sudden fame. Inspired, the triumphant translator appropriated the authorship of these works-he got so carried away that he even began signing everything with the name “Shafi Vazeh.” Within a single year, multiple editions of The Songs of Mirza Shafi had to be printed, and the books sold out instantly. In 1887, an operetta about the popular poet, titled Die Lieder des Mirza Chaffee, was staged in Berlin. Meanwhile, the true author died in obscurity and poverty in Tiflis. Deprived and forgotten in life, he was robbed even after his death. The Azerbaijani cemetery behind the Tbilisi Botanical Garden was demolished following the war, and no one in the poet’s homeland raised a voice to defend the memory of their illustrious countryman.

Illustration of Vazeh in Tausend und ein Tag im Orient by Friedrich von Bodenstedt (Wikipedia)

There is a famous saying: “One man in the field is not a warrior,” yet the self-sacrifice of our poets, artists, and scholars-fated to live in foreign lands-who inscribed their names in golden letters in the history of other peoples’ science and art, proves otherwise. We have no right to forget them, if only because we continue to benefit from the fruits of their labors, reflected in and giving a powerful impetus to the development of many fields of science and art.

And today, when we hear the sound of genius in young, still-maturing talents, we should not be surprised, for with such an inheritance, it could hardly be otherwise. Our history and spirituality are like a carpet woven of countless silken threads of numerous talents whose names are too many to list. We have every right to be proud of them and, above all, we must remember them!

It was once said in conversation by Goethe that he was very fortunate not to have been born in the East:

“You know, next to such towering figures of poetry as Saadi, Omar Khayyam, Nizami, and Fuzuli, I would simply have gone unnoticed…”

Share on social media