Middle Corridor. Photo credit: TITR

The latest launch of a multimodal transport route linking China, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan marks another decisive step in Beijing’s grand effort to redraw the map of Eurasian connectivity.

The October 15 ceremony in Kashgar, China, was not just a logistical milestone; it symbolized the steady materialization of China’s strategic ambition to weave Central Asia ever more tightly into its orbit through trade, infrastructure, and transit corridors.

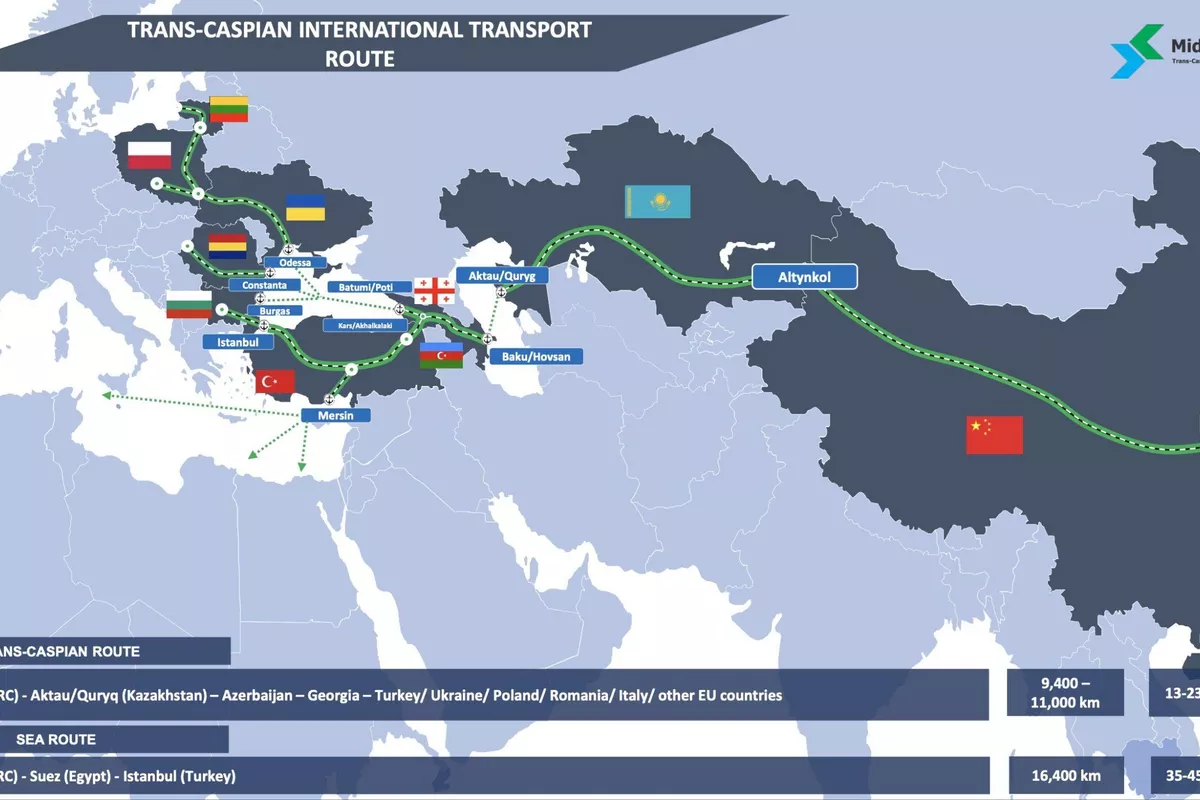

The convoy of seven trucks that left Kashgar, carrying lighting equipment and consumer goods toward the Kyrgyz border, represents more than routine commerce. It is the visible expression of Beijing’s vision for the Middle Corridor, a trade artery designed to bypass Russia, diversify export routes to Europe, and create new economic lifelines across the heart of the continent.

According to Cai Tuanjie, Director of the Department of Transport Services at China’s Ministry of Transport, this new corridor reflects the political will of both Central Asian states and China to deepen practical cooperation.

Photo credit: uzdaily.uz

Indeed, the route opens not only to Europe but also to markets in South Asia and the Middle East, reinforcing Beijing’s flagship Belt and Road Initiative.

But this project is also about timing and opportunity. As global supply chains shift and sanctions reshape trade patterns, China is filling the void with infrastructure diplomacy. The new Kashgar-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan-Turkmenistan route will eventually link up with Azerbaijan via the Caspian Sea, providing a seamless land-sea bridge that trims delivery times from 20 to just 10 days and slashes transport costs by nearly a third.

Beijing’s commitment to strengthening regional logistics is unmistakable. In recent months, new railway lines have been opened across China’s interior, while older ones have been modernized to serve the growing Central Asian demand. The new Tianjin-Tashkent branch alone has shortened transit by over 800 kilometers, cutting delivery times by up to three days.

Meanwhile, trade between Hubei Province and Central Asia continues to surge. Since 2021, Wuhan has evolved into a key logistics hub, dispatching regular trains to Almaty and beyond. By April 2025, freight services from Wuhan to Central Asia reached a monthly capacity of 440 TEUs (7,500 tons of cargo), underscoring the intensity of trade across this emerging corridor.

Statistics tell a clear story. In 2024, rail freight between China and Kazakhstan hit a record 32 million tons, a 13-percent increase from the previous year. That figure is expected to climb beyond 33 million tons this year, with Kazakhstan exporting nearly twice as much to China as it imports. Raw materials continue to dominate outbound traffic, while consumer goods flow in the opposite direction.

For the smaller Central Asian states, these routes are lifelines. Kyrgyzstan, long dependent on overland trade through Kazakhstan, now sees the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway, whose construction began in December 2024, as a game-changer. Backed by 51 percent Chinese investment and the remainder split between Bishkek and Tashkent, the line will finally give landlocked Kyrgyzstan direct access to the Belt and Road network.

Photo credit: railwaygazette.com

This is not simply a matter of logistics. It is about strategic balance in a rapidly changing Eurasia. Every kilometer of the new track and every shortened delivery time strengthen China’s role as the central economic engine of the continent. For decades, Russia was the undisputed transit power of the post-Soviet space. Now, Beijing is quietly and methodically redrawing those routes - one railway, one corridor, one partnership at a time.

If completed as planned, the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway could become one of the defining infrastructure projects of the 21st century, reshaping trade, accelerating growth, and reconfiguring geopolitical dependencies from the Caspian to the Pacific. For the nations of Central Asia, it offers opportunity; for China, it represents enduring influence. And for Eurasia as a whole, it marks yet another step toward a future where all roads and railways lead to Beijing.

Share on social media