photo: China Academy

Russia’s declaration that it intends to build a nuclear power plant on the Moon within the next decade is not merely a futuristic talking point. It is a statement about how Moscow sees power, permanence, and relevance in the next phase of space exploration. Read carefully, it reveals as much about geopolitics and narrative positioning as it does about engineering ambition.

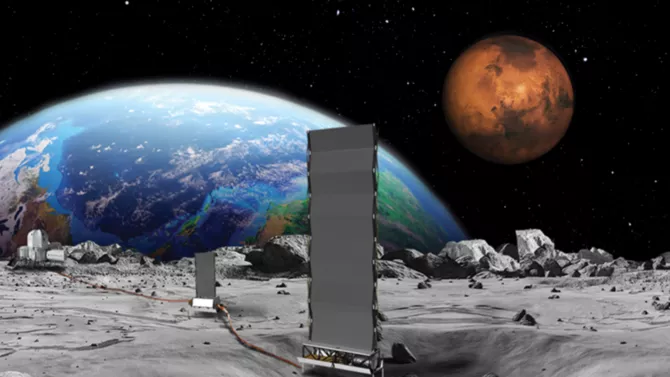

At a practical level, the idea is not irrational. Sustained human or robotic presence on the Moon requires a stable and continuous energy source. Solar power, while useful, is constrained by the lunar environment. Nights last roughly two weeks, temperatures are extreme, and dust degrades equipment. Any base meant to function year-round, support habitation, run laboratories, or enable industrial experiments needs reliable baseload electricity. Nuclear power solves that problem in a way no other technology currently can. In this sense, a lunar reactor is not exotic; it is logical.

Where the claim becomes more complex is in timing and intent. Saying “within a decade” transforms a long-term concept into a political signal. It suggests urgency, capability, and strategic resolve. For Russia, whose civil space program has faced setbacks and growing constraints, such language serves an important function. It reframes the conversation away from missed milestones and toward future infrastructure. It is less about what has been lost and more about what is being built.

photo: BBC

The proposal also cannot be separated from broader alignments. The idea of a nuclear-powered lunar base is closely tied to the Russia-China vision for an alternative lunar architecture, one positioned alongside, and in quiet competition with, the U.S.-led Artemis framework. A nuclear plant implies permanence. Permanence implies rules, standards, and influence. In space politics, infrastructure is authority. Whoever provides power defines what is possible around it.

From a technical standpoint, a lunar nuclear reactor is feasible but unforgiving. The challenge is not theoretical physics; it is execution. A reactor must be compact, passively safe, shielded, and capable of surviving launch, transit, landing, deployment, and long-term operation in one of the harshest environments imaginable. Each stage depends on mature launch systems, precision landers, surface robotics, and sustained funding. Announcing a timeline is easy. Delivering an integrated system on schedule is not.

This is why the decade-long horizon should be read cautiously. It is best understood as an ambition rather than a guarantee. Russia has deep expertise in nuclear engineering and long experience with space nuclear systems, but recent lunar missions have demonstrated how narrow the margin for error is. The Moon does not reward symbolic gestures. It rewards consistency, redundancy, and institutional patience.

photo: Innovationnewsnetwork

There is also a governance dimension that remains largely unspoken. Nuclear power in space, even for civilian use, carries political sensitivity. Questions of launch safety, accident scenarios, contamination, and transparency will inevitably arise. A reactor on the Moon is not a weapon, but it exists in a strategic environment where trust is limited. Without clear international norms and confidence-building measures, such projects risk becoming sources of suspicion rather than cooperation.

Yet even if timelines slip, the announcement itself has strategic value. It signals that the next phase of lunar activity is not about brief visits or prestige landings, but about systems that enable long-term presence. Power generation is the first real bottleneck of lunar settlement. Solve that, and everything else becomes conceivable: extended habitation, resource utilization experiments, large-scale science, and sustained logistics.

In the end, Russia’s lunar nuclear plant plan should neither be dismissed as science fiction nor accepted as an imminent reality. It is a serious concept framed in aspirational terms, shaped as much by geopolitical messaging as by engineering logic. Whether it materializes by the mid-2030s will depend less on announcements and more on steady, verifiable progress. But even as a declaration, it underscores a critical shift in space competition: the race is no longer just to arrive, but to stay, build, and endure.

Share on social media