photo: News.az

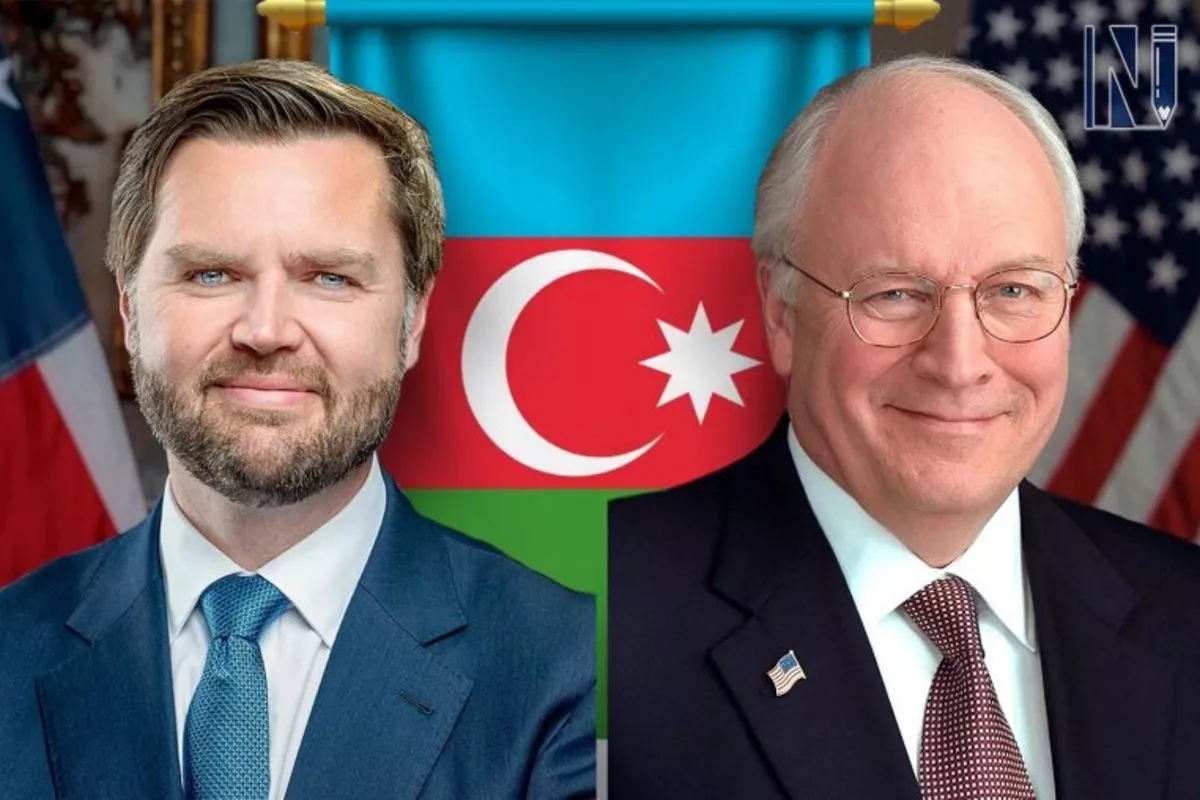

By comparing U.S. Vice President Dick Cheney’s visit to the South Caucasus in 2008 with the recent trip by J.D. Vance, one can trace the evolution of Washington’s approach to the region - and, at the same time, see which elements of that strategy have remained unchanged.

In 2008, Cheney’s itinerary included Azerbaijan and Georgia, but not Armenia. This reflected the rigid and pragmatic logic guiding Washington at the time. Energy and security were at the core of U.S. priorities. The focus was on infrastructure that enabled alternative routes for hydrocarbon supplies to bypass Russia and Iran. The key element of this architecture was the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan oil pipeline. In this context, the Baku-Tbilisi axis served as the backbone of the American presence in the region. Azerbaijan was the source through which the U.S. strategy was realized, while Georgia was the country that allowed this strategy to extend toward Europe. European energy security itself was far from Washington’s primary concern. The real objective was to sideline Moscow and Tehran, and Azerbaijan’s capabilities, combined with Georgian transit, provided a unique opportunity to do so.

photo: AZERTAC

Despite reports by the U.S. State Department, other institutions, and human rights NGOs, Washington has historically tended to favor Armenia over Azerbaijan. Looking ahead, it is worth noting that even today Yerevan’s diplomatic breakthrough across the Atlantic is directly linked to its relations with Baku. In 2008, those relations were openly hostile, and Azerbaijan did not view its neighbor as a potential partner in any regional projects. For this reason, Armenia was of no practical interest to Cheney at the time.

Armenia in that period lay outside the configuration of interest to the United States. Its foreign policy space, defense, and security sectors were tightly embedded in the Russian system, leaving extremely limited room for independent maneuvering. From Washington’s perspective, this meant an absence of practical interest - whether in energy, logistics, or regional security. Even if relations between Azerbaijan and Armenia had been positive at the time, the overwhelmingly dominant Russian factor would still have discouraged the U.S. from engaging with Yerevan.

2026: New Routes, the Same Logic

By February 2026, the picture looked markedly different. J.D. Vance visited Yerevan and then traveled on to Baku. Georgia was not included in the itinerary. What changed? A closer look shows that the principle itself did not change - only the context did. The principle remains that the United States does not conduct courtesy visits; American visits are made where there is a concrete U.S. interest.

This does not mean that Washington has completely lost interest in Georgia. The issue lies elsewhere. Two years earlier, the previous U.S. administration severed relations with Tbilisi over the so-called foreign agents law and what Washington perceived as pressure on democracy and a pro-Russian orientation of the Georgian leadership. The current administration, given its pragmatism and relative immunity to “democratic” hysteria, would likely not have taken such a step. Notably, Washington and Tbilisi have already agreed to begin discussions aimed at restoring relations.

This time, however, the U.S. vice president did not visit Georgia because relations have not yet been fully restored. Moreover, Western interests continue to be implemented through the Baku-Tbilisi linkage, leaving little need for adjustment. In the specific context of Vance’s visit, Georgia was not a key element of the current agenda, underscoring a shift in U.S. focus from traditional political symbols to practical mechanisms of influence.

Washington’s primary interest today is concentrated along Armenia’s southern borders. For the first time, the United States has gained an opportunity not merely to enter the South Caucasus, but to maintain a long-term presence there - directly on the border with Iran. This fundamentally alters the region’s geopolitical landscape. An American presence also neutralizes the threat of Russian interference in Armenia’s affairs and will facilitate the gradual displacement of Moscow’s interests.

As for Azerbaijan, it remains a constant in the U.S. South Caucasus strategy. Just as in 2008, it continues to occupy a central role. In the other two countries, American interests may shift in tone, recede, and later return. Azerbaijan, however, is always present in this framework. It holds a unique position as the country around which a new configuration of security and communications is now taking shape in the South Caucasus. Following the end of the Karabakh conflict and the dismantling of the previous status quo, conditions have emerged for revising the region’s transport and economic geography across the entire space from the Caspian to the Mediterranean.

Today’s agenda includes the unblocking of regional communications, the potential intersection of East-West and North-South land routes in the South Caucasus, and the idea of sustainable regional integration - previously impossible due to the conflict. In this context, Armenia has, for the first time since gaining independence, begun to be viewed not as an isolated element but as a potential part of a broader logistical and political framework.

photo: AZERTAC

Why Washington Turned its Attention to Yerevan

U.S. interest in Armenia is not the result of a sudden shift in American policy or a consequence of internal reforms within the republic itself. It stems from the transformation of the regional environment following the end of the conflict and the advancement of a peace agenda. In this post-conflict setting, Armenia has found a place within discussions on prospective transport corridors through the South Caucasus.

During the years of conflict, these corridors bypassed Armenia entirely, as Azerbaijan was consistently their initiator and investor. The so-called “Trump route,” or TRIPP, would allow Armenia, for the first time, to become part of international transit. Implemented under U.S. patronage and ensuring a long-term American presence, it would also serve as a security guarantee for Yerevan.

MIt is crucial to understand that Armenia has not become an object of attention in and of itself, but rather within a new regional reality shaped by fundamental changes in the balance of power.

Without these changes, Yerevan would have remained, as before, a peripheral element of U.S. policy.

photo: AIR Center

A Recurring Pattern

A comparison of U.S. vice-presidential visits to the South Caucasus in 2008 and 2026 reveals several enduring patterns.

First, the United States structures its South Caucasus strategy around states and routes capable of influencing the region’s overall architecture.

Second, Azerbaijan occupies a central place in this logic in both cases.

Third, interest in Armenia arises only when it is embedded in a broader process of regional transformation.

Conclusion

The visits of Dick Cheney and J.D. Vance, separated by nearly two decades, illustrate not so much a change in the paradigm of U.S. policy as its adaptation to new realities. After the 2020 war, Azerbaijan emerged as a middle power, further reinforcing its leadership status in the region. As Baku’s interests expanded westward, Armenia found itself drawn into this evolving framework and is now being considered, or seeking to be considered by Washington, as part of a Baku-Yerevan linkage. It will take time before such a linkage approaches the stability of the Baku-Tbilisi axis. Nevertheless, Washington’s interest in fostering it is already evident.

The South Caucasus remains a space of interest for the United States, but the form of that interest is determined by the actual distribution of power, control over communications, and the ability to shape the regional agenda. In both 2008 and 2026, it was precisely these factors that defined who stood at the center of Washington’s attention, and who merely followed the changes unfolding around them.

Share on social media