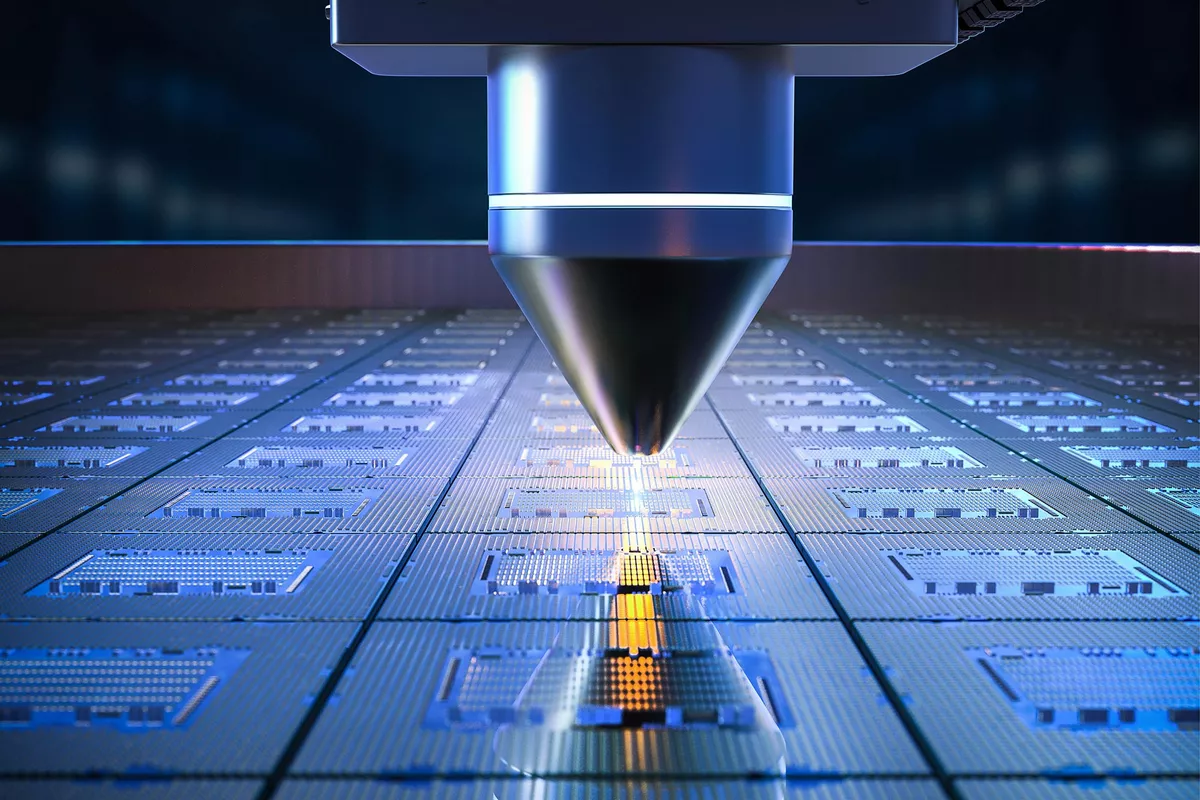

photo: SciTechDaily

The statement made by U.S. Vice President J.D. Vance in Yerevan became one of the most widely discussed moments of his visit to the region. According to the American official, the U.S. administration has approved plans by NVIDIA to establish chip production in Armenia - chips that, in his words, “do not exist in most countries of the world.”

For a South Caucasus state situated in a complex geopolitical environment and possessing a limited industrial base, such a statement appears not merely unexpected but fundamentally unconventional. For that very reason, it calls not for an emotional reaction, but for a thoughtful and multilayered analysis.

The region in which Armenia is situated has traditionally been viewed as an arena of competition among external centers of power, rather than as a space for hosting elements of critically important global technological infrastructure. The South Caucasus is characterized by unresolved conflicts, closed borders, fragile alliances, and constant pressure from larger actors. In this context, the launch of a high-tech production facility linked to microelectronics and artificial intelligence appears either as an extremely risky step or as part of a much broader and carefully calculated U.S. strategy.

Armenia is a country that hosts Russian military bases, where border security is partially carried out by structures affiliated with Russia’s FSB, and where the influence of both Russia and Iran remains a systemic factor in domestic and foreign policy alike. These circumstances create a unique yet simultaneously vulnerable environment. Any project involving sensitive technologies automatically falls under heightened scrutiny - from U.S. allies as well as from Washington’s strategic adversaries. Therefore, American investments in high-tech manufacturing in Armenia cannot be viewed solely as a commercial initiative.

What chips might be produced

It is important to establish a basic clarification from the outset. The term “chip production” covers a wide range of technological processes and does not necessarily imply the manufacturing of the most advanced microchips using 3-5 nanometer process nodes. Such technologies are currently concentrated in a very narrow circle of countries and companies, primarily in Taiwan and South Korea, and are subject to strict U.S. export controls and political oversight. With a high degree of probability, more realistic and politically safer options are being considered for Armenia.

First, this may involve specialized accelerators and related chips. These would not be flagship, next-generation GPUs, but auxiliary processors, controllers, networking solutions, and components for data centers and server systems. Such microchips play an important role in digital infrastructure while not belonging to the most sensitive elements of military development.

Second, production could focus on “second-tier” AI infrastructure chips. These are microchips used in cloud platforms, data storage and processing systems, AI training clusters, and corporate computing environments. While these technologies are dual-use in nature, they are often formally classified as civilian.

Third, Armenia may be of interest as a platform for research and development, assembly, testing, and advanced packaging, as well as for the creation of engineering centers and pilot production lines. In this case, the focus would not be on a full lithography cycle, but on critical stages without which modern microelectronics cannot function. Thus, even if the chips produced are indeed “absent in most countries of the world,” this does not imply a level comparable to the most tightly controlled and strategically sensitive U.S. developments.

Where such chips are used

Even microchips that do not belong to the absolute technological cutting edge have critically important applications. They are used in artificial intelligence and machine learning systems - from big data analysis to forecasting and recognition technologies. They underpin cloud services and data centers, without which the modern digital economy cannot exist. They are employed in defense and dual-use technologies, including logistics, modeling, cybersecurity, and the management of complex systems. Finally, they are used in autonomous systems and robotics, including unmanned platforms and industrial solutions. Therefore, the key issue is not only the technological level of the chips themselves, but also who controls the infrastructure, the personnel, the supply chains, and the channels of access to these technologies.

Why Armenia?

The United States may view Armenia through several different lenses simultaneously. The first factor is human capital. The country does indeed have a strong engineering and mathematical tradition, a developed IT sector, and comparatively low operating costs relative to the EU or the United States. The second factor is geopolitical. Launching American high-tech production is not merely an investment - it is an anchor of influence. Such projects inevitably require a reassessment of security arrangements, access to strategic infrastructure, and the role of third-country presence. The third factor is political signaling. Even the public announcement of NVIDIA’s plans serves both as an element of pressure and as a test of Yerevan’s readiness for a potential shift in its foreign-policy balance.

Two possible scenarios

As a result, two basic scenarios emerge. The first is technologically limited. In this case, the project would involve chips that do not represent critical strategic value, and production would remain within the realm of civilian and commercial technologies. The second scenario is politically assertive. Here, Washington operates on the assumption that Armenia may, over time, be drawn out from under dominant Russian and Iranian influence, with chip production becoming part of a long-term strategy to entrench U.S. presence in the South Caucasus.

It is no coincidence that Azerbaijani political analyst Rasim Musabayov directly points to the paradox of the situation: such statements are being made in a country saturated with Russian and Iranian presence. This suggests either that the chips in question are not among the most technologically sensitive, or that the United States is preparing for a radical shift in the balance of influence in Armenia.

Chip production is not merely about economics or technology. It is a matter of sovereignty, security, and strategic choice. If NVIDIA’s plans in Armenia are implemented, they will become one of the clearest signals of how the United States intends to reshape the architecture of influence in the South Caucasus, and what role it envisions for Yerevan in that process. The only remaining question is whether Armenia itself is prepared for the consequences that inevitably follow such decisions.

By Tural Heybatov

Share on social media