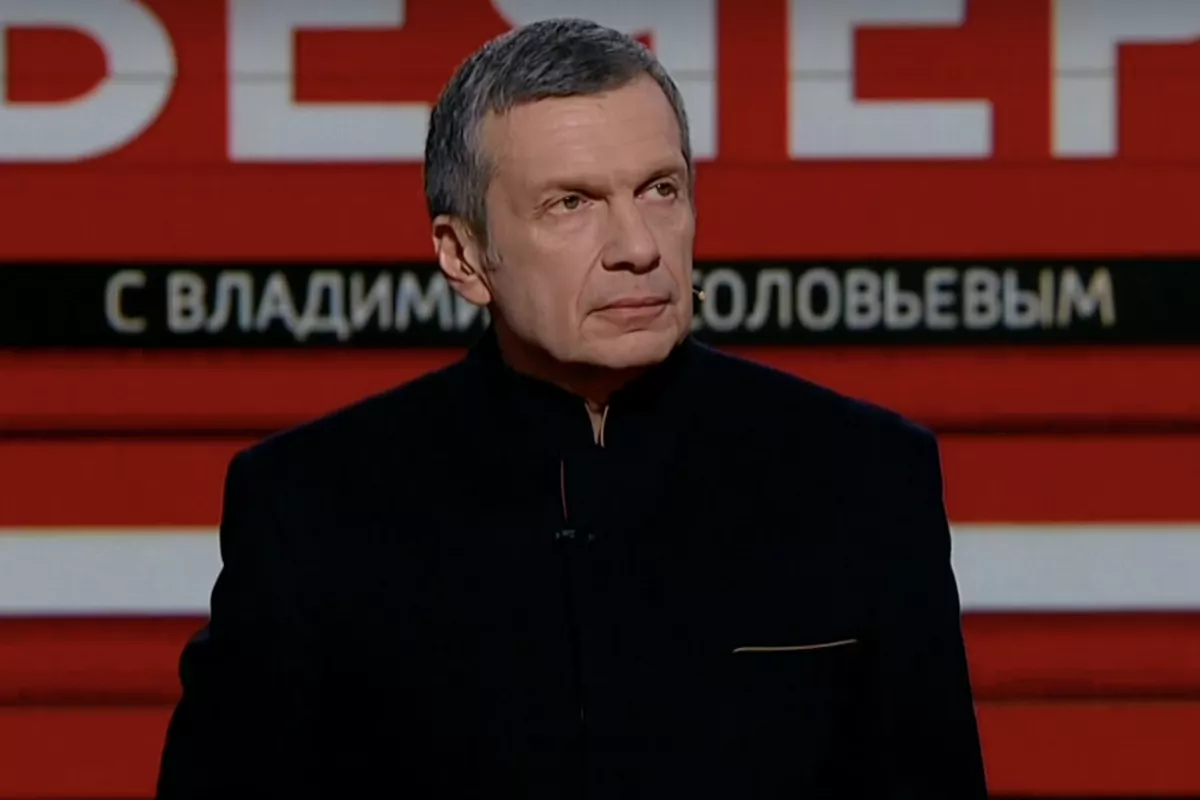

Photo credit: Russia1

Vladimir Solovyov, the Kremlin’s most recognizable television propagandist, has long functioned more as a political shock instrument than as a journalist. His role is not to inform, but to test how far the boundaries of acceptable rhetoric can be pushed before real consequences follow. Most of the time, his outbursts are dismissed abroad as domestic theater - a grotesque spectacle intended for Russia’s internal audience. At times, however, Solovyov crosses the line between propaganda and what begins to sound uncomfortably close to policy.

That moment came in his latest broadcast, when he openly discussed the possibility of launching so-called “special military operations” not only in Ukraine, but also in Armenia and across Central Asia. In doing so, Solovyov did more than offer another inflammatory soundbite. He articulated a worldview in which large parts of Eurasia are treated as Russia’s colonial possession - a “zone of influence” where international law, sovereignty, and diplomatic norms simply do not apply.

Even more revealing was the justification he chose. Solovyov argued that Moscow should take inspiration from the United States, which, in his view, ignored international law when it acted against Venezuela. According to this logic, if Washington can impose its will beyond its borders, so should Russia.

“What is happening in Armenia is far more painful for us than what is happening in Venezuela. The loss of Armenia would be a gigantic problem. Problems in Central Asia could also be gigantic for us. And we must clearly define our goals and objectives… Hell with international law. If it was necessary to launch a special military operation in Ukraine for national security, why can’t we launch one in other parts of our zone of influence?” Meduza quoted him as saying.

This was not a slip of the tongue. It was a carefully structured argument designed to normalize the idea that military force is a legitimate tool for keeping former Soviet states in line.

Solovyov has made similar statements before, including open calls for military action against Azerbaijan during periods of tension between Moscow and Baku. What makes this episode different, however, is the geopolitical moment in which it occurred. Donald Trump’s controversial intervention against Venezuela, widely criticized for violating international norms, has created a dangerous precedent. It has revived the notion that great powers can redraw political realities without meaningful consequences.

Solovyov is correct in one limited sense: the United States did demonstrate that international law is often subordinate to power. But he conveniently ignores that the Kremlin has operated under exactly that logic for years. Russia did not wait for Trump to start eroding the global order. From Crimea to Ukraine, Moscow has challenged the foundations of the post-Cold War system long before Washington acted in Venezuela.

What is new, however, is the possibility that Russia may now believe a new, informal partition of the world is emerging. Western analysts have repeatedly speculated that Trump and Vladimir Putin view global politics through the prism of spheres of influence, with the United States dominating the Western Hemisphere and Russia claiming the East. If that perception takes hold in Moscow, Solovyov’s rhetoric ceases to be mere propaganda. It becomes a trial balloon for how far Russia might push this logic in its own neighborhood.

Armenia immediately grasped the danger. According to Armenian media, Russia’s ambassador, Sergey Kopyrkin, was summoned to the Foreign Ministry and handed a formal note of protest expressing “deep outrage” over Solovyov’s remarks. The Armenian government stressed that such statements are incompatible with friendly relations between Moscow and Yerevan.

photo: Aircenter.az

This reaction is telling. Armenia remains formally allied with Russia through the CSTO, the Eurasian Economic Union, and the Customs Union. A Russian military base remains stationed on Armenian soil. Economically and militarily, Yerevan is still deeply tied to Moscow. Yet since the 2020 war, Armenia has increasingly questioned whether those ties provide real security. Moscow’s failure to protect Armenia’s interests created a political opening for a gradual reorientation toward the West.

That makes Solovyov’s threats even more destabilizing. They reinforce the perception that Russia views Armenia not as a partner, but as a possession.

The irony is striking. In 2013, Armenia’s then-president Serzh Sargsyan awarded Solovyov the Order of Honor for strengthening Armenian-Russian friendship, largely because of his vocal support for Armenia in the Karabakh conflict and his consistently anti-Azerbaijani position. Today, the same figure has become one of Armenia’s most aggressive critics. His television program was blocked in Armenia in 2024 after repeated personal attacks on Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan.

Central Asia has been treated with even less respect. Whenever Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, or other regional states display political independence, Solovyov responds with open hostility. In his latest broadcast, he referred to Central Asia as “ours,” making clear that he views the region as Russia’s colonial backyard.

That worldview no longer matches reality. For decades, Central Asia remained locked into Russian economic, political, and security structures by inertia. But the rise of China and the institutionalization of the Middle Corridor have dramatically altered the region’s strategic environment. Central Asian states now have real alternatives. They are no longer willing to subordinate their futures to Moscow’s imperial nostalgia.

Yet, like Armenia, these countries remain members of Russian-led organizations such as the CSTO and the Eurasian Union. This means that, despite everything, Russia still retains influence and partners in the region. It is not too late for Moscow to preserve a workable relationship with its neighbors.

What threatens that balance most is not Western pressure, but its own propaganda.

Every statement like Solovyov’s, delivered by a figure widely understood to be close to the Kremlin, is interpreted abroad not as entertainment, but as a signal of Russia’s intentions. In an atmosphere of high tension and low trust, propaganda becomes indistinguishable from policy.

If Russia continues to tolerate a media culture driven by imperial fantasies, great-power chauvinism, and nostalgia for the Soviet past, it will not strengthen its position. It will isolate itself.

And the Kremlin should not be surprised if, after this scandal, Central Asian states move even more decisively toward Türkiye and China, while Armenia increasingly looks beyond Moscow when building its relationship with the United States.

Solovyov may believe he is defending Russian power. In reality, he is helping to dismantle what remains of Russia’s alliances.

Share on social media