Photo credit: KHAMENEI.IR / AFP

At present, the world is holding its breath as it watches developments surrounding Iran. What lies ahead for a country whose history spans 2,500 years?

Will the obscurantist regime of the ayatollahs endure, or will a modernized monarchy with elements of democracy and respect for human rights return? Or perhaps Iran will become a Western-style democratic republic with all its attributes? Today, probably no one can give a definitive answer. Yet the question itself is unavoidable and far from academic.

Iran is one of the most important countries in the Middle East, possessing enormous natural resources, a territory of 1.648 million square kilometers, and a population approaching 93 million people. Moreover, it is a multinational and multi-confessional state, which inevitably raises the issue of preserving the country’s territorial integrity.

At one time, Vladimir Lenin wrote that Russia faced two possible forms of government: either a tsarist monarchy with its triune ideology of autocracy, Orthodoxy, and nationality, or a dictatorship of the proletariat based on Marxism and proletarian internationalism. Why did he frame the issue in such stark terms? Because Russia was a multinational country inhabited by followers of different faiths. It is well known that after the February Revolution of 1917, when power passed to the democratic Provisional Government, the former empire quickly began to fragment into national states. The same process occurred as a result of Gorbachev’s perestroika, when the Communist Party lost its monopoly on power.

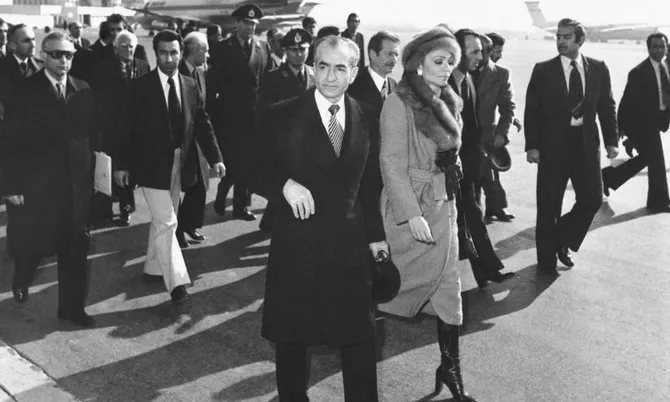

Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and Empress Farah at Mehrabad Airport, Tehran, 16 January 1979. Photo: AP

If one draws a parallel, something similar could happen to Iran. Although any comparison is imperfect, slogans calling for the return of the shah are increasingly heard, and this is no coincidence. The country needs a symbol of unity, and in this sense the Pahlavi dynasty represents historical continuity and the possibility of avoiding separatist tendencies.

The current Islamic regime is built on a religious foundation. At its core lies the principle of velayat-e faqih, according to which the head of state - the rahbar (Supreme Leader) - must be the most authoritative faqih, a Shiite theologian and jurist. He exercises control over the legislative, executive, and judicial branches, acting as a “guardian” (velayat) over the state. Iran is a classic example of a theocracy. Even the shah did not possess powers comparable to those of the rahbar, who, according to official Shiite doctrine reflected in Article 5 of Iran’s Constitution, is considered the legitimate representative or deputy (vali-ye amr) of the Twelfth Imam, Muhammad ibn al-Hasan.

The Supreme Leader determines the domestic and foreign policy of the Islamic Republic of Iran, approves decisions of the president and government, oversees the appointment of a number of ministers, serves as commander-in-chief of the armed forces, appoints judges, Friday prayer leaders, provincial governors, and the top military leadership, including the chief of the Joint Staff and the commander of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC).

The IRGC combines the functions of an army, police, and intelligence service. It conducts social and ideological work inside the country and abroad, while its former members actively participate in Iran’s political and economic life. According to various estimates, this structure directly or indirectly controls between 20 and 40 percent of Iran’s economy.

The rahbar is elected for life. The only feature distinguishing this system from an absolute monarchy is the formal prohibition on hereditary succession. However, the current Supreme Leader is reportedly attempting to circumvent this restriction by transferring power to his son.

The second most important figure in the state is the president, whose position roughly corresponds to that of a prime minister. In foreign policy, the regime’s objectives include exporting the Shiite version of Islam and establishing influence in Muslim countries. Another central goal is combating Western influence and destroying the State of Israel. Enormous resources are therefore devoted to nuclear and missile programs, as well as to supporting such terrorist organizations as Hamas, Hezbollah, and others.

Before the Islamic Revolution of 1979, Iran was a parliamentary monarchy in which real power belonged to the shah. The first Iranian Constitution consisted of two parts: the Fundamental Law adopted in 1906 and the crucial Supplementary Laws adopted in 1907. In 1911, a law on universal elections was passed, laying the foundations of Iran’s electoral system that largely remain in place today: universal suffrage, direct and secret elections based on proportional representation, and the abolition of property qualifications. In 1963, women received the right to vote.

When people speak of “Iran under the shah,” they usually present two opposing images. The first is modernization, oil money, miniskirts in Tehran, Western brands, factories under construction, and a sense that the country was on the verge of joining the club of wealthy nations. The second is darker: secret police, political arrests, a widening gap between rich and poor, resentment among the clergy, and the feeling that change was being imposed by force.

Iran in the 1950s-1970s was indeed a country undergoing rapid transformation - so rapid that many people were unable to adapt to the new conditions and became embittered observers on the sidelines. In effect, they found themselves excluded from the process, swelling the ranks of the regime’s opponents. Moreover, much of the population consisted of semi-literate rural dwellers who received most of their information about events from the imam during Friday prayers.

Photo credit: Majid Saeedi/Getty Images

According to Mohammad Reza Pahlavi’s vision, Iran was to become a modern nation state with a strong army, a large industrial base, an educated population, and a stable economy. Hence the emphasis on education, Western technologies, friendship with Israel, and other elements of modernization. The shah embraced the idea of a “great leap”: not waiting for society to mature organically, but accelerating change through the power of the state. This created the central tension of the era - a constant race between what was “needed now” and what people were “ready to accept.”

As a result, Iran did indeed accelerate. But “modernization from above” has a side effect: if changes are not internalized by society, they are perceived as imposed, even if they are objectively beneficial. The reforms revealed that cities were growing wealthier faster than villages; educated strata were expanding while social mobility lagged behind; inflation hit those living on fixed incomes; and public expectations rose faster than living standards. People began to compare themselves not with the past, but with promises.

Here lies the paradox: the shah sought to modernize society, and in doing so helped create a layer of students, intellectuals, urban youth, and entrepreneurs who began demanding political participation and freedom. The most painful dividing line ran not between “rich and poor,” but between competing visions of what Iran should be.

For part of the urban population, the shah’s era is associated with openness to the world: cinema, music, fashion, gender equality, and more. This is why posters from that period are remembered today - bold, colorful, almost European in spirit. But for a significant segment of society at the time, this image was perceived as an insult to tradition. Religious leaders and conservative groups saw not “progress,” but a loss of influence.

In the end, the seventh century temporarily triumphed over the twentieth. Yet progress cannot be stopped. Ideology eventually ceases to function and begins to destroy itself. This is why many Iranians feel nostalgia for the past, which, against the backdrop of today’s economic collapse, brutal repression, and public executions, appears as a lost paradise.

Share on social media