photo: railfreight.com

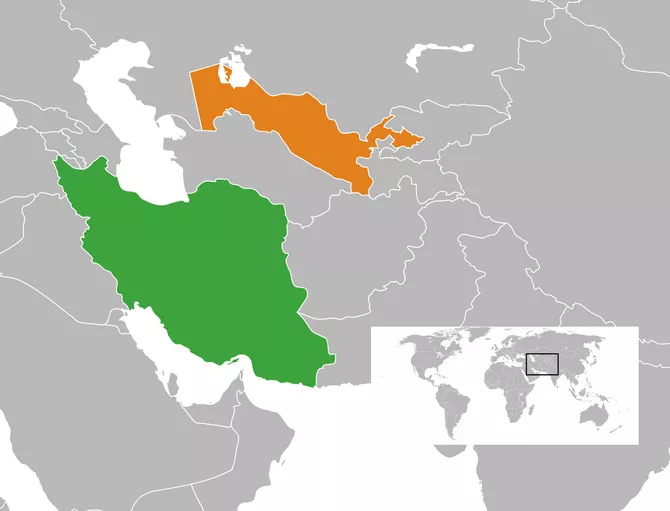

The decision to launch regular container trains along the route linking Uzbekistan with Türkiye via Turkmenistan and Iran represents far more than a logistics upgrade. It is a geopolitical signal, an economic calculation, and a long-overdue adjustment to Eurasia’s fragmented transport geography. At a time marked by supply chain shocks, sanctions risks, and intensifying competition over transit corridors, the initiative reflects a shared understanding among participating states that connectivity has become a form of strategic power.

At its core, the route addresses a persistent structural problem. Central Asia has long struggled with the constraints of landlocked geography, while Anatolia has sought to consolidate its role as a bridge between Asia and Europe. Existing routes have often been slow, costly, or overly dependent on a single transit country. A regular, predictable container service introduces reliability, and in modern trade, reliability is a decisive asset.

While announcements of new corridors are common, translating them into functioning services is far more difficult. What distinguishes this initiative is its emphasis on operations. Regular container trains require harmonised customs procedures, coordinated schedules, compatible rail infrastructure, and concrete commercial commitments from shippers. This moves the project beyond symbolism and into the realm of practical infrastructure diplomacy.

photo: president.uz

Political backing is a critical factor. The agreement was reached in Ankara with the participation of Uzbek President Shavkat Mirziyoyev and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, signalling that the project is not a marginal technical exercise. High-level endorsement helps reduce coordination costs across government agencies and state-owned rail operators - areas where similar initiatives often stall.

The timing is also significant. Global trade patterns are shifting away from excessive reliance on maritime chokepoints. Disruptions in the Red Sea, evolving sanctions regimes, and rising insurance costs have increased interest in overland alternatives. While the so-called Middle Corridor has gained attention, it remains incomplete without reliable east-west and north-south connections. The Uzbekistan-Turkmenistan-Iran-Türkiye route strengthens that broader network.

For Uzbekistan, the advantages are clear. Export diversification depends on fast and predictable access to external markets. Cotton yarn, fertilisers, copper products, and a growing range of manufactured goods require efficient routes to Mediterranean ports and European consumers. Rail transport offers significant time savings compared with maritime routes that involve lengthy detours.

Photo: Devid Monteleone

For Türkiye, the corridor reinforces its ambition to serve as a central logistics hub. Rail connectivity from Central Asia feeds into Turkish ports, industrial zones, and onward links to Europe, supporting domestic manufacturing, logistics services, and Ankara’s broader vision of becoming a key node in Eurasian trade.

Iran’s role is often viewed primarily through a geopolitical lens, but geography remains a determining factor. Its rail network provides the most direct land bridge between Central Asia and Anatolia. Participation in the corridor allows Tehran to monetise its transit potential, attract investment into rail infrastructure, and ease economic isolation through practical cooperation. While individual transit revenues may be modest, their strategic value lies in anchoring Iran within regional supply chains.

Turkmenistan, meanwhile, occupies a pivotal position as the territorial link between Uzbekistan and Iran. Its cooperation is indispensable, and the corridor creates incentives for more pragmatic engagement and gradually more open transport policies - an outcome long sought by regional traders.

photo: TASS

Political will alone, however, will not determine success. The private sector will ultimately judge the corridor on cost, transit time, and reliability. Regular container trains must compete with maritime shipping on price-adjusted speed. Although rail transport is typically more expensive per unit, it becomes competitive when time sensitivity, inventory costs, and predictability are taken into account.

A key challenge will be aggregating sufficient volumes. Individual exporters rarely generate enough cargo to fill entire trains. State-backed logistics operators, freight forwarders, and trade promotion agencies will need to bundle shipments, guarantee capacity, and absorb initial losses. If early trains run under capacity, confidence will erode quickly; if they run full, positive network effects are likely to follow.

One recurring weakness of Eurasian corridor projects has been an overemphasis on grand announcements at the expense of technical standardisation. Customs clearance times, digital documentation, and dispute-resolution mechanisms matter far more than ceremonial launches. A container delayed at a border due to paperwork can instantly negate rail’s speed advantage.

The corridor’s viability will therefore depend on common digital platforms, pre-clearance systems, and transparent tariff regimes. Incremental bureaucratic reforms will matter more than political rhetoric. If these measures are implemented effectively, the route can become commercially sustainable rather than politically subsidised.

photo: Anadolu

Connectivity reshapes diplomacy. Countries that trade together regularly develop habits of cooperation, and rail schedules create daily interdependence that soft power initiatives struggle to match. Over time, transport corridors can help ease political frictions by raising the cost of disruption.

There is also a security dimension. Diversified routes reduce vulnerability to external shocks and coercion. For landlocked states, having multiple exit options provides strategic insurance; for transit states, indispensability enhances diplomatic leverage.

Optimism, however, should be tempered with realism. Sanctions affecting Iran complicate insurance, payments, and equipment procurement. Rail gauge differences require efficient transshipment or dual-gauge solutions, while seasonal bottlenecks, particularly in desert and mountainous segments, test infrastructure resilience.

Regional competition is also intensifying. Alternative routes via the Caspian Sea, the South Caucasus, or Russia will continue to vie for cargo. To succeed, this corridor must prove its value through performance, not politics.

photo: Kazinform

Ultimately, the launch of regular container trains along this route is a litmus test. It will reveal whether Eurasian cooperation can move beyond declarations to disciplined execution. If trains run on time, borders clear cargo efficiently, and tariffs remain predictable, the corridor will speak for itself.

If not, it risks joining the long list of underperforming initiatives that looked impressive on the map but failed in practice.

The Uzbekistan-Turkmenistan-Iran-Türkiye container train initiative reflects a mature understanding of 21st-century geopolitics, where infrastructure is influence and logistics is leverage. Its promise lies not in grand rhetoric but in daily performance: trains departing on schedule, containers moving without friction, and businesses planning with confidence.

If the participating countries commit to operational excellence, this rail link could reshape trade flows, rebalance regional power dynamics, and provide a model of pragmatic cooperation in a fragmented world. Failure, however, would carry costs not only in lost revenue but also in diminished credibility.

Share on social media