photo: cscr.pk

In their joint analysis, Awais Akmal and Dr. Marriyam Siddique examine the pragmatic forces reshaping regional trade routes across Central Asia. Writing on the website of the Center for Strategic and Contemporary Research (CSCR), the authors argue that infrastructure readiness, port efficiency, and corridor reliability - rather than political alignment - explain why Iranian ports continue to outperform Pakistani alternatives in attracting Central Asian trade flows.

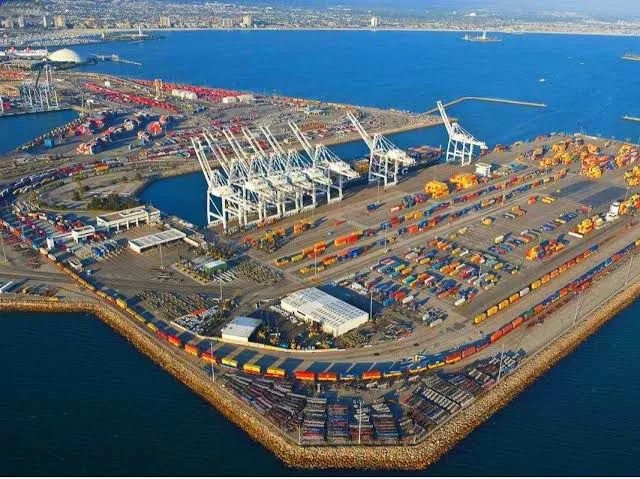

Despite the often cited strategic location of Pakistan at the crossroads of South Asia, Central Asia, China, and the Indian Ocean, the Central Asian Republics (CARs) continue to bypass the Pakistani ports in favour of the Iranian alternatives. This paradox has been accentuated once again by the recent expansion of the Central Asian trade flows through the Bandar Abbas and Chabahar Ports, which directly challenge Pakistan’s long-standing claim of being the most natural gateway for the CARs to the sea. While the geography of Pakistan is often framed as a strategic asset, the persistence of this trend raises a fundamental question: why does this geography fail to translate into actual access? The Caspian Post republishes the article.

Pakistan should be the obvious choice on paper. Gwadar and Karachi offer the shortest maritime access to the warm waters for the landlocked Central Asian economies. Theoretically, this proximity should reduce the transportation costs, shorten the delivery times, and integrate Central Asia into the global supply chain more effectively. Yet, in practice, geography alone has failed to deliver these outcomes. The growing preference of the CARs for the Iranian ports reveals a critical structural barrier: the inability of Pakistan to compete economically and institutionally in an increasingly crowded and competitive connectivity landscape.

The advantage of Iran is not merely geographical; it is transactional. The Iranian ports provide relatively predictable transit regimes, established rail and road connectivity, and clear commercial terms for the exporters. Even under the shadow of the international sanctions, Iran has demonstrated an ability to prioritise functional logistics over strategic posturing. Particularly, the Chabahar Port has evolved into a multi-user port, catering to the regional trade interests beyond geopolitics, including those of the CARs, which are seeking diversification away from the Russian-controlled routes and the congested northern corridors.

Iranian ports will continue to outperform Gwadar in practice unless Pakistan shifts decisively from symbolic connectivity to competitive economic facilitation.

Crucially, Iran has invested in the continuity of corridors. The integration of ports with inland railways, customs harmonisation, and logistics hubs has allowed CAR exporters to move goods with fewer interruptions and administrative uncertainties. For landlocked economies, where each additional delay raises costs and risks, such reliability outweighs political considerations. As a result, Iranian ports are increasingly being considered not necessarily as ideal corridors, but as workable ones. This is the distinction that matters far more in commercial decision-making.

In contrast, the connectivity narrative of Pakistan remains largely aspirational. The Gwadar Port is frequently presented as a future hub of regional trade and a linchpin of transcontinental connectivity. Despite this, it today lacks the throughput capacity, hinterland integration, and commercial incentives required to attract Central Asian exporters. Road and rail connectivity between Gwadar, Quetta, and onward routes toward Afghanistan remain underdeveloped, while regulatory bottlenecks continue to discourage consistent commercial use. The decision is economic, not ideological, for the CARs: ports are chosen based on cost efficiency, reliability, and regulatory predictability. Despite its strategic rhetoric, Pakistan has yet to offer these in a competitive and sustained manner.

photo: Rafi Group

This gap has been further widened by Pakistan’s approach to economic diplomacy. Engagement with the CARs has largely been framed through strategic symbolism-high-level visits, memoranda of understanding, and ambitious connectivity visions-rather than through the granular mechanics of trade facilitation. However, the CARs prioritise transit guarantees, tariff clarity, insurance coverage, and investment protection. While Iran provides operational corridors backed by administrative continuity, Pakistan continues to promise future connectivity contingent on political stability and long-term projects.

The competition with Iranian ports also exposes a deeper policy inconsistency within Pakistan’s regional outlook. Islamabad has not articulated a transit strategy focused on Central Asia based on commercial realism. Instead, connectivity initiatives are often subsumed within broader geopolitical frameworks involving great power competition and regional security concerns. This over-politicisation and subsequent uncertainty are pushing partners towards corridors that prioritise commerce over strategic alignment.

Moreover, the CARs are no longer dependent on a single route. They actively hedge their connectivity options through Russian corridors, Iranian ports, eastward routes through China, and the Trans-Caspian. Therefore, Pakistan competes in a diversified market rather than occupying a natural monopoly. In such an environment, access must be earned through efficiency, not inherited through geography.

If Pakistan is to alter this trajectory, specific and immediate policy changes are required. First, Islamabad must introduce a dedicated transit tariff regime for Central Asian trade that offers transparent, competitive cost structures to directly rival those of Iranian ports. Second, the Gwadar Port must be operationalised as a purely commercial entity rather than being sustained as a geopolitical emblem. This requires fast-tracking rail and road connectivity linkages through Quetta and onward to the Afghan border; without this physical and regulatory integration, Gwadar’s strategic value will remain largely notional.

Third, Pakistan should establish a Trade Facilitation Cell specifically for the CARs, staffed by logistics experts, trade economists, and regulatory specialists rather than generalist diplomats. This body must be mandated to resolve transit bottlenecks, standardise customs procedures, and negotiate corridor-specific arrangements with Central Asian partners, ensuring that symbolic diplomacy gives way to problem-solving governance. Furthermore, it is essential to decouple connectivity from broader political uncertainties. Central Asian exporters require the assurance that access to Pakistani ports will not be disrupted by political tensions, border closures, or security crises. Without credible guarantees of continuity, even the greatest geographical proximity cannot outweigh the reliability offered by alternative routes through Iran or the Caspian Sea. Ultimately, connectivity corridors cannot function as episodic projects; they must operate as predictable commercial systems.

The geography of Pakistan is an opportunity, but not a guarantee. In an era where the CARs possess multiple corridors to global markets, access is earned through performance rather than assumed through maps. Iranian ports will continue to outperform Gwadar in practice unless Pakistan shifts decisively from symbolic connectivity to competitive economic facilitation. The lesson is clear: geography creates the possibility, but policy creates the access. The challenge for Pakistan is no longer where it is located, but whether it can deliver what regional trade partners need-consistently and competitively.

Share on social media