photo: Yahoo

Today’s global system is effectively built around two superpowers - the United States and China. Almost every major political, economic, and security process in the world is, directly or indirectly, tied to the interaction and rivalry between Washington and Beijing. For this reason, events unfolding inside either of these countries cannot be viewed as purely domestic. They inevitably generate ripple effects far beyond national borders.

Recent months have demonstrated this pattern with striking clarity. Tensions have intensified around Venezuela, which has long supplied substantial volumes of oil to China. Pressure on Iran has also grown, even though Iranian hydrocarbons remain one of the pillars supporting the energy security of the world’s second largest economy. These parallel developments illustrate how the external confrontation between the two largest economic powers increasingly intersects with internal political dynamics, especially in China.

Against this backdrop, reports of serious changes within the top leadership of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) deserve particular attention. They are not simply about corruption. They reflect a much deeper transformation of China’s political and military architecture.

photo: wgi

Xi Jinping today stands as one of the most powerful and authoritative leaders in the history of the People’s Republic of China. His political ascent was gradual, methodical, and carefully calibrated. In 2002, when China underwent a transition to the so-called “fourth generation” of leadership and Hu Jintao became head of state, Xi Jinping entered the Central Committee of the Communist Party for the first time. That period was marked by widespread corruption scandals, and it was in this environment that Xi built a reputation as a clean, disciplined, and pragmatic official - a figure capable of bridging divides between old revolutionary cadres and younger technocrats.

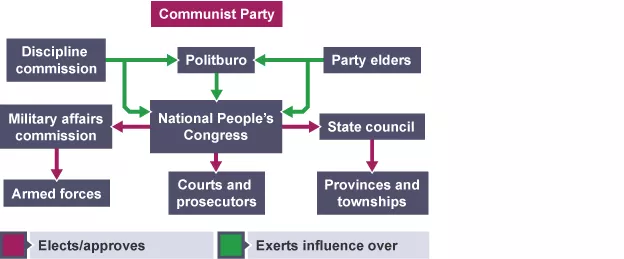

In March 2008, the National People’s Congress elected Xi Jinping vice president of China. From that moment, the question of succession was effectively settled. Four years later, in 2012, Xi became general secretary of the Communist Party and chairman of the Central Military Commission (CMC), placing the party, the state, and the armed forces under unified leadership.

Since then, Xi has overseen a sweeping reconfiguration of China’s internal and external posture. The PLA has undergone large-scale structural reforms. China’s economic outreach has been elevated to a new level through the Belt and Road Initiative. A sovereign and tightly controlled national internet space has been constructed. Social policy has been geared toward achieving what the leadership calls “moderate prosperity” for the majority of citizens.

On the international stage, China under Xi has moved far beyond its former status as a regional power. It is now a global actor without whose participation no major international issue can realistically be resolved. The abolition in 2018 of constitutional term limits for the presidency only formalised what was already evident: Xi Jinping intended to remain at the helm for the long term. In 2023, he secured a third presidential term while simultaneously retaining the positions of party general secretary and chairman of the CMC.

photo: TASS

It is within this political context that the events of January 24 must be understood. On that day, China’s Ministry of National Defense announced investigations involving senior military figures, including Zhang Youxia, a member of the Politburo and vice chairman of the Central Military Commission, and Liu Zhenli, a member of the CMC and chief of the Joint Staff Department.

These are not marginal figures. Zhang Youxia, in particular, has long been regarded as one of Xi Jinping’s closest military associates - a man deeply embedded in the system of promotions, staff appointments, and strategic planning.

Following reports that Zhang had been stripped of his posts, the PLA’s official newspaper Jiefangjun Bao published a commentary framing the developments in explicitly ideological terms. The article urged servicemen to strictly follow the party’s political line and to eliminate alien and hostile influence from within the armed forces. Such language is significant. Analysts note that similar rhetoric accompanied earlier political campaigns in China that were less about combating corruption and more about justifying broad political purges.

Chinese political commentator Cai Shenkun, who resides in the United States, wrote on X on January 23 that, in addition to Zhang, at least 17 high-ranking officers had been taken into custody. Linling Wei, chief China correspondent for The Wall Street Journal, stated in a January 24 post that the consequences of these developments were likely far from over. She emphasised that under Zhang and Liu’s leadership, thousands of officers had been promoted to senior posts, meaning that the investigation could extend deep into the military hierarchy.

photo: Xinhua

Importantly, warning signs appeared even before the official announcements. Observers noted Zhang’s absence from the opening ceremony of a high-level training programme for provincial- and ministerial-level officials. In China’s closed political system, such absences almost always signal either serious health issues or involvement in an internal political struggle.

All of this is unfolding against the backdrop of a continuing anti-corruption campaign inside the armed forces. In October last year, the Communist Party announced the dismissal of nine senior generals, including former CMC members He Weidong, Miao Hua, and Lin Xiangyang. The communiqué of the Fourth Plenum of the 20th Central Committee confirmed that He Weidong and Miao Hua were expelled from the party. Shortly thereafter, the PLA’s newspaper declared that corruption would not be tolerated in the military.

According to official statistics, in 2025 alone, 69 officials at ministerial or regional level and above were held accountable for corruption. More than one million corruption cases were investigated nationwide, and 983,000 individuals were punished. Such figures indicate not a one-time campaign but a permanent state of political mobilisation.

In an interview with Bloomberg, U.S. Ambassador to China David Perdue described the detention of Zhang Youxia as a sign of Xi Jinping’s determination to establish full control over the armed forces. He called the prosecution of such a senior officer an “important event”. Zhang has been accused of abuse of power, including allegedly accepting large sums of money in exchange for promotions within bodies responsible for overseeing military research, development, and procurement. Earlier accusations also suggested that he passed technical data related to China’s nuclear weapons programme to the United States.

photo: Xinhua

What makes these allegations especially striking is that Zhang was for many years considered Xi’s trusted confidant and political ally. Today, according to available information, only Xi Jinping himself and Zhang Shengmin, head of the CMC’s Commission for Discipline Inspection and appointed CMC vice chairman last October, remain at the top of the Commission.

Why is this happening now?

The most convincing explanation points to Taiwan.

Despite China’s remarkable progress in military modernisation, the country has not fought a major war in decades. A large-scale operation against Taiwan would be the most complex and risky military endeavour in modern Chinese history. It would test not only weapons systems but also the political loyalty, cohesion, and psychological readiness of the armed forces.

Within China’s elite, there are likely differing views on how to handle this challenge. Some may believe that concessions to Washington, including partial retreat from certain external markets, could reduce the likelihood of war. From Xi Jinping’s perspective, such thinking undermines China’s long-term strategic position and threatens national sovereignty.

In this context, even the perception of wavering loyalty becomes intolerable.

There is no confirmed evidence of an attempted coup or a planned arrest of Xi Jinping. However, the logic of preventive action is consistent with Xi’s governing style. He prefers to neutralise potential threats before they fully materialise.

China is not a country where mass street protests can overthrow the leadership. If a serious challenge were ever to arise, it would almost certainly originate within the system - above all within the military. That reality explains why Xi is tightening control over the PLA with such determination.

photo: Xinhua

Another important trend is the growing influence of air force and missile force commanders in senior appointments. This reflects a strategic shift toward a modern model of warfare in which aerospace and missile capabilities play a decisive role, while traditional ground forces become less central.

The old PLA elite - generals shaped by the wars of previous decades - is gradually leaving the scene. A new generation of commanders is emerging, selected primarily for political reliability and personal loyalty rather than battlefield experience.

For outside observers, the key conclusion is this: the purges in China’s military are not signs of imminent collapse or chaos. They are symptoms of a profound transformation in China’s governance model.

The country is moving away from a system, in which key institutions retained limited autonomy, toward one in which all strategic levers are concentrated in a single political centre.

In the short term, this may enhance control and decision-making speed. But it also carries long-term risks. A system that suppresses internal debate becomes less resilient to unexpected crises and more prone to strategic miscalculation.

China’s military purge, therefore, is not merely about corruption. It is about power, loyalty, and preparation for a future that Beijing increasingly views as one of unavoidable confrontation.

Share on social media